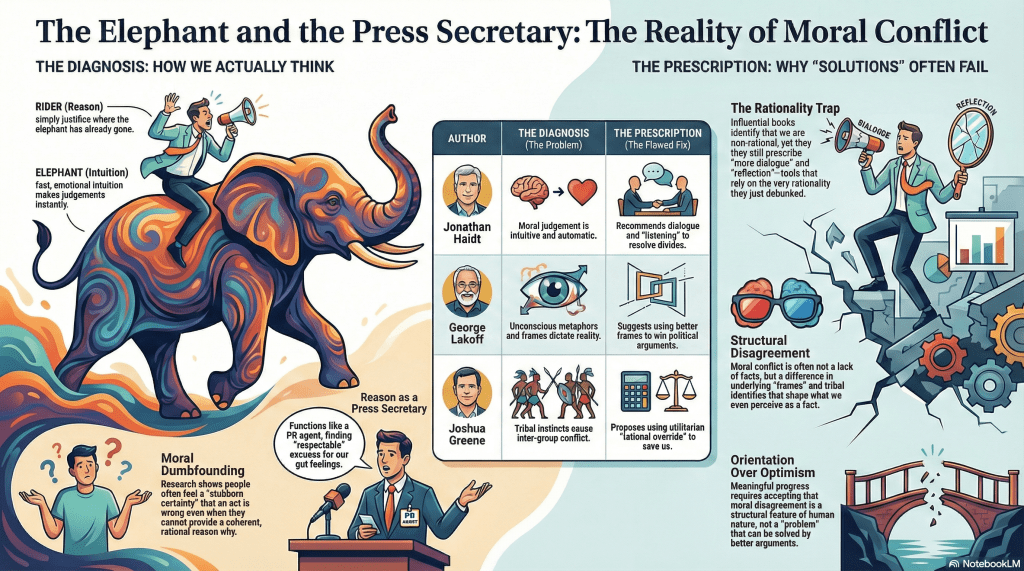

Over the past few decades, moral psychology has staged a quiet coup against one of our most cherished fantasies: that human beings are, at bottom, rational moral agents. This is not a fringe claim. It is not a Twitter take. It is the mainstream finding of an entire research programme spanning psychology, cognitive science, linguistics, and neuroscience.

We do not reason our way to moral conclusions. We feel our way there. Instantly. Automatically. And only afterwards do we construct reasons that make the judgment sound respectable.

This is not controversial anymore. It is replicated, taught, and celebrated. And yet, if you read the most influential books in this literature, something strange happens. The diagnosis is devastating. The prescription is reassuring.

I’ve just published a long-form video walking through five canonical books in moral psychology that all uncover the same structural problem, and then quietly refuse to live with the implications.

What follows is a brief guide to the argument.

The shared discovery

Across the literature, the same conclusions keep reappearing:

- Moral judgement is intuitive, not deliberative

- Reasoning is largely post-hoc

- Emotion is not noise but signal

- Framing and metaphor shape what even counts as a moral fact

- Group identity and tribal affiliation dominate moral perception

In other words: the Enlightenment picture of moral reasoning is wrong. Or at least badly incomplete.

The rider does not steer the elephant. The rider explains where the elephant has already gone.

Where the books go wrong

The video focuses on five widely read, field-defining works:

- The Righteous Mind (reviewed here and here… even here)

- Moral Politics (mentioned here – with Don’t Think of an Elephant treated as its popular sequel)

- Outraged! (reviewed here)

- Moral Tribes (reviewed here)

Each of these books is sharp, serious, and worth reading. This is not a hit piece.

But each follows the same arc:

- Identify a non-rational, affective, automatic mechanism at the heart of moral judgement

- Show why moral disagreement is persistent and resistant to argument

- Propose solutions that rely on reflection, dialogue, reframing, calibration, or rational override

In short: they discover that reason is weak, and then assign it a leadership role anyway.

Haidt dismantles moral rationalism and then asks us to talk it out.

Lakoff shows that framing is constitutive, then offers better framing.

Gray models outrage as a perceptual feedback loop, then suggests we check our perceptions.

Greene diagnoses tribal morality, then bets on utilitarian reasoning to save us.

None of this is incoherent. But it is uncomfortable. Because the findings themselves suggest that these prescriptions are, at best, limited.

Diagnosis without prognosis

The uncomfortable possibility raised by this literature is not that we are ignorant or misinformed.

It is that moral disagreement may be structural rather than solvable.

That political conflict may not be cured by better arguments.

That persuasion may resemble contagion more than deliberation.

That reason often functions as a press secretary, not a judge.

The books sense this. And then step back from it. Which is human. But it matters.

Why this matters now

We are living in systems that have internalised these findings far more ruthlessly than public discourse has.

Social media platforms optimise for outrage, not understanding.

Political messaging is frame-first, not fact-first.

AI systems are increasingly capable of activating moral intuitions at scale, without fatigue or conscience.

Meanwhile, our institutions still behave as if one more conversation, one more fact-check, one more appeal to reason will close the gap. The research says otherwise.

And that gap between what we know and what we pretend may be the most important moral problem of the moment.

No solution offered

The video does not end with a fix. That’s deliberate.

Offering a neat solution here would simply repeat the same move I’m criticising: diagnosis followed by false comfort. Sometimes orientation matters more than optimism. The elephant is real. The elephant is moving.And most of us are passengers arguing about the map while it walks.

That isn’t despair. It’s clarity.