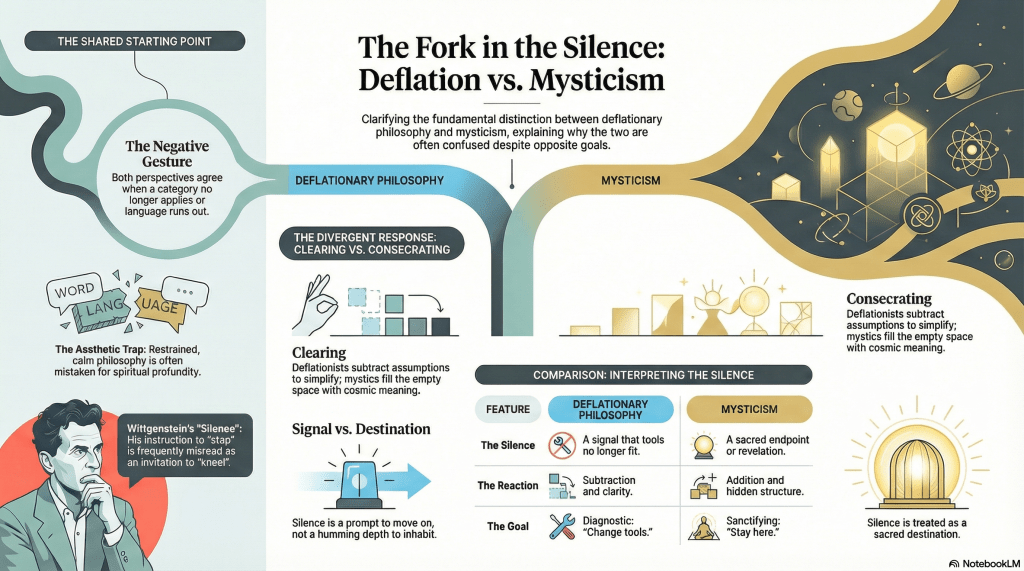

I recently shared a post calling out mystics, trying to fill spaces I deflate, but I am self-aware enough that I can be guilty, too. I worry about Maslow’s Law of the Instrument. Deflationary philosophy likes to imagine itself as immune to excess. It dissolves puzzles, clears away bad questions, and resists the urge to add metaphysical upholstery where none is needed. No mysteries, thank you. No hidden depths. Just conceptual hygiene. This self-image is mostly deserved. But not indefinitely. This post is an attitude check.

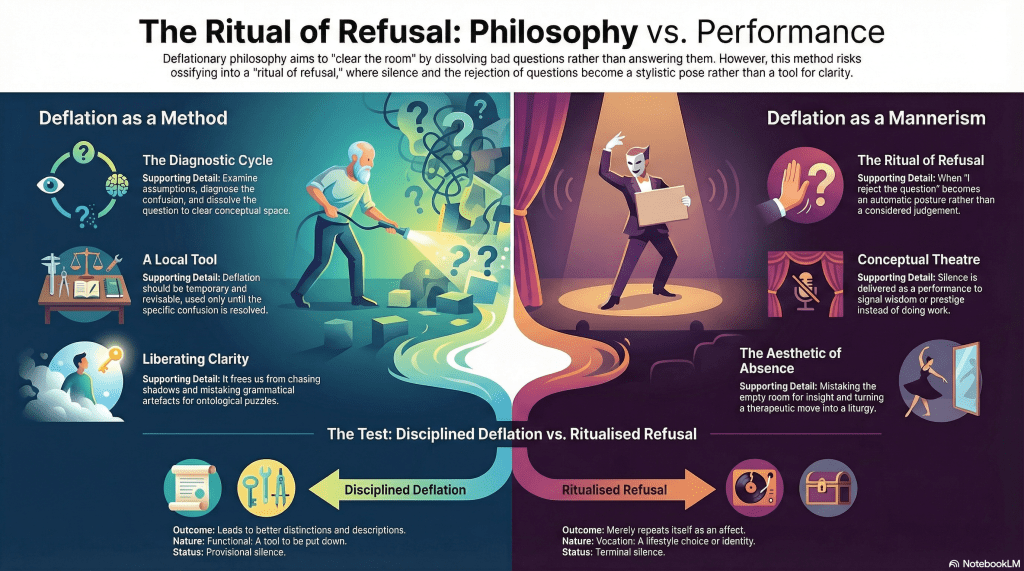

Because deflation, like anything that works, can ossify. And when it does, it doesn’t inflate into metaphysics. It hardens into something more embarrassing: a ritual of refusal.

From method to mannerism

Deflation begins as a method:

- A question is posed.

- Its assumptions are examined.

- The confusion is diagnosed.

- The question dissolves.

- Everyone goes home.

At its best, this is liberating. It frees us from chasing shadows and mistaking grammatical artefacts for ontological puzzles. The trouble begins when the gesture outlives the job.

What was once a diagnostic move becomes a stylistic tic. Refusal becomes automatic. Silence becomes performative. ‘There is nothing there’ is delivered not as a conclusion, but as a posture. At that point, deflation stops doing work and starts doing theatre.

I am often charged with being negative, a pessimist, a relativist, and a subjectivist. I am sometimes each of these. Mostly, I am a Dis–Integrationist and deflationist, as it were. I like to tear things apart – not out of malice, but seeing that certain things just don’t sit quite right.

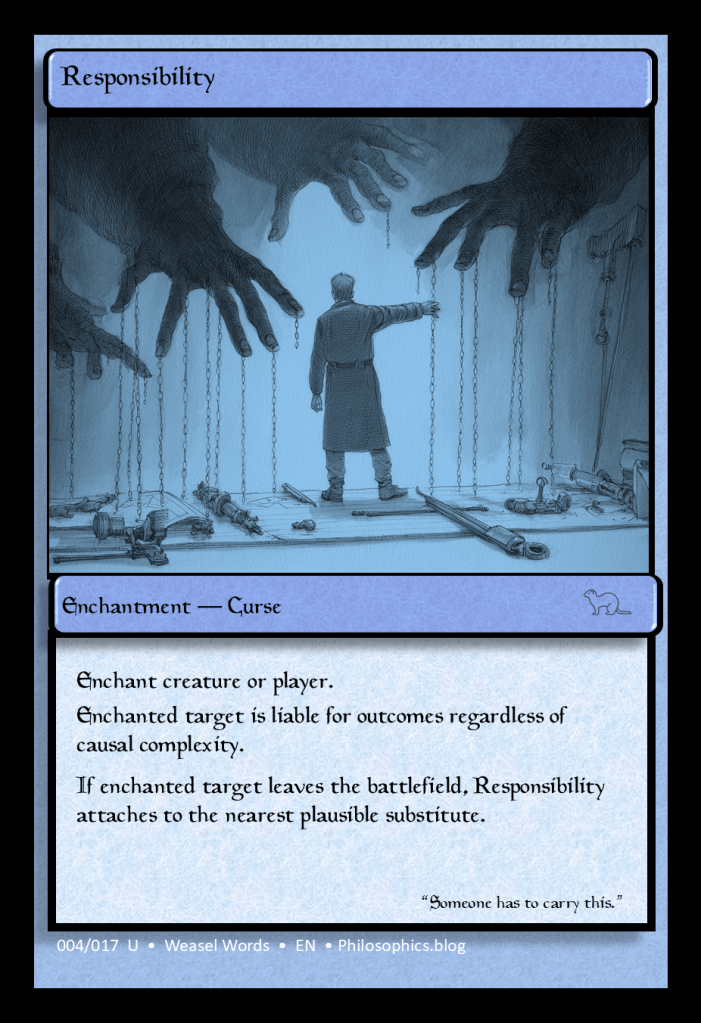

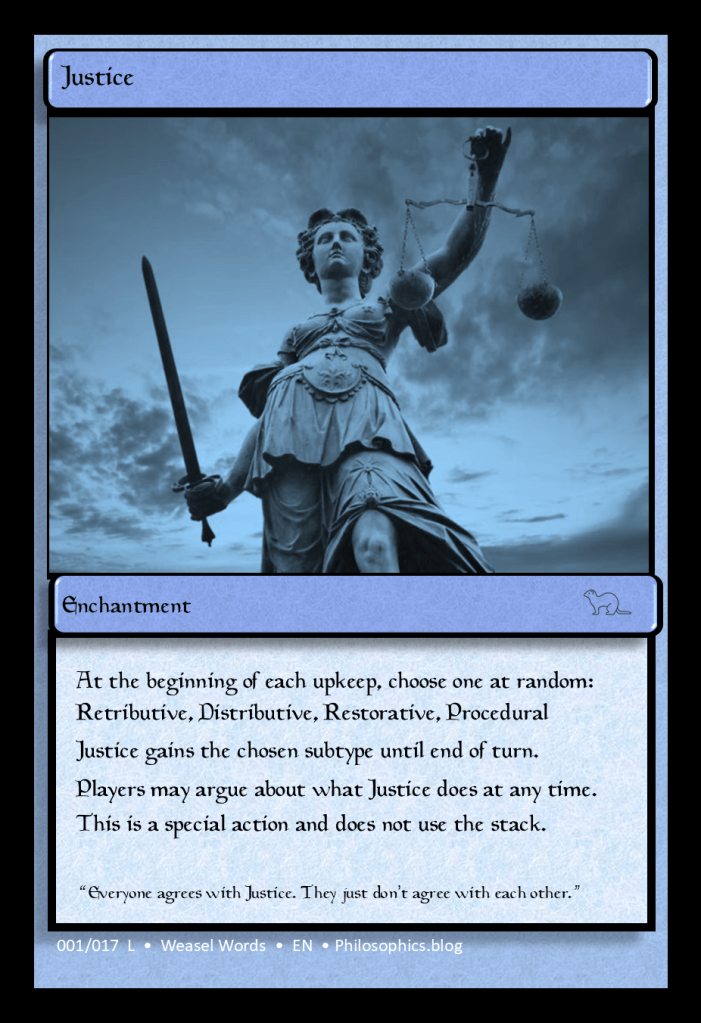

Another thing I do is to take things at face value. As I came up through the postmodern tradition, I don’t trust metanarratives, and I look for them everywhere. This is why I wrote A Language Insufficiency Hypothesis (LIH), and even more so, the Mediated Encounter Ontology (MEOW). Some words carry a lot of baggage and connotation, so I want to be sure I understand the rawest form. This is why I rail on about weasel words like truth, justice, freedom, and such.

I also refrain from responding if I am not satisfied with a definition. This is why I consider myself an igntheist as opposed to an atheist. Functionally, I am the latter, but the definition I’d be opposing is so inane that it doesn’t even warrant me taking a position.

The prestige of saying less

There is a quiet prestige attached to not answering questions. Refusal sounds serious. Restraint sounds wise. Silence, in the right lighting, sounds profound. This is not an accident. Our intellectual culture has learned to associate verbal minimalism with depth, much as it associates verbosity with insecurity. Deflationary philosophers are not immune to this aesthetic pull.

When ‘I reject the question’ becomes a default response rather than a considered judgement, deflation has slipped from method into mannerism. The absence of claims becomes a badge. The lack of commitments becomes an identity. One is no longer clearing space, but occupying emptiness.

This is how deflation acquires a style – and styles are how rituals begin.

Apophasis without God

Mysticism has its negative theology. Ritualised deflation develops something similar.

Both rely on:

- refusal to name

- insistence on limits

- reverent quiet

The difference is meant to be procedural. Mysticism stops at the silence. Deflation is supposed to pass through it. But when deflation forgets that its silence is provisional, it starts to resemble the thing it set out to criticise. Absence becomes sacred again, just without the cosmology. The metaphysician worships what cannot be said. The ritualised deflationist admires themselves for not saying it. Neither is doing conceptual work anymore.

A brief and unavoidable Wittgenstein

This is where Ludwig Wittgenstein inevitably reappears, not as an authority, but as a warning. Wittgenstein did not think philosophy ended in silence because silence was holy. He thought philosophy ended in silence because the confusion had been resolved. The ladder was to be thrown away, not mounted on the wall and admired. Unfortunately, ladders make excellent décor.

When deflation becomes ritual, the therapeutic move freezes into liturgy. The gesture is preserved long after its purpose has expired. What was meant to end a problem becomes a way of signalling seriousness. That was never the point.

A diagnostic test

There is a simple question that separates disciplined deflation from its ritualised cousin:

- Is this refusal doing explanatory work, or is it being repeated because it feels right?

- If silence leads to better distinctions, better descriptions, or better questions, it is doing its job.

- If silence merely repeats itself, it has become an affect.

And affects, once stabilised, are indistinguishable from rituals.

Deflation is local, not terminal

The corrective is not to abandon deflation, but to remember its scope.

Deflation should be:

- local rather than global

- temporary rather than terminal

- revisable rather than aestheticised

Some questions need dissolving. Some need answering. Some need rephrasing. Knowing which is which is the entire discipline. Deflation is not a worldview. It is not a temperament. It is not a lifestyle choice. It is a tool, and like all tools, it should be put down when it stops fitting the task.

Clearing space is not a vocation

There is a temptation, once a room has been cleared, to linger in it. To admire the quiet. To mistake the absence of furniture for the presence of insight. But clearing space is not a vocation. It is a task. Once it is done, staying behind is just another way of refusing to leave. And refusal, repeated without reason, is no longer philosophy. It is choreography.