Now that A Language Insufficiency Hypothesis has been put to bed — not euthanised, just sedated — I can turn to the more interesting work: instantiating it. This is where LIH stops being a complaint about words and starts becoming a problem for systems that pretend words are stable enough to carry moral weight.

What follows is not a completed theory, nor a universal schema. It’s a thinking tool. A talking point. A diagram designed to make certain assumptions visible that are usually smuggled in unnoticed, waved through on the strength of confidence and tradition.

The purpose of this diagram is not to redefine justice, rescue it, or replace it with something kinder. It is to show how justice is produced. Specifically, how retributive justice emerges from a layered assessment process that quietly asserts ontologies, filters encounters, applies normative frames, and then closes uncertainty with confidence.

Most people are willing to accept, in the abstract, that justice is “constructed”. That concession is easy. What is less comfortable is seeing how it is constructed — how many presuppositions must already be in place before anything recognisable as justice can appear, and how many of those presuppositions are imposed rather than argued for.

The diagram foregrounds power, not as a conspiracy or an optional contaminant, but as an ambient condition. Power determines which ontologies are admissible, which forms of agency count, which selves persist over time, which harms are legible, and which comparisons are allowed. It decides which metaphysical configurations are treated as reasonable, and which are dismissed as incoherent before the discussion even begins.

Justice, in this framing, is not discovered. It is not unearthed like a moral fossil. It is assembled. And it is assembled late in the process, after ontology has been assumed, evaluation has been performed, and uncertainty has been forcibly closed.

This does not mean justice is fake. It means it is fragile. Far more fragile than its rhetoric suggests. And once you see that fragility — once you see how much is doing quiet, exogenous work — it becomes harder to pretend that disagreements about justice are merely disagreements about facts, evidence, or bad actors. More often, they are disagreements about what kind of world must already be true for justice to function at all.

I walk through the structure and logic of the model below. The diagram is also available as a PDF, because if you’re going to stare at machinery, you might as well be able to zoom in on the gears.

Why Retributive Justice (and not the rest of the zoo)

Before doing anything else, we need to narrow the target.

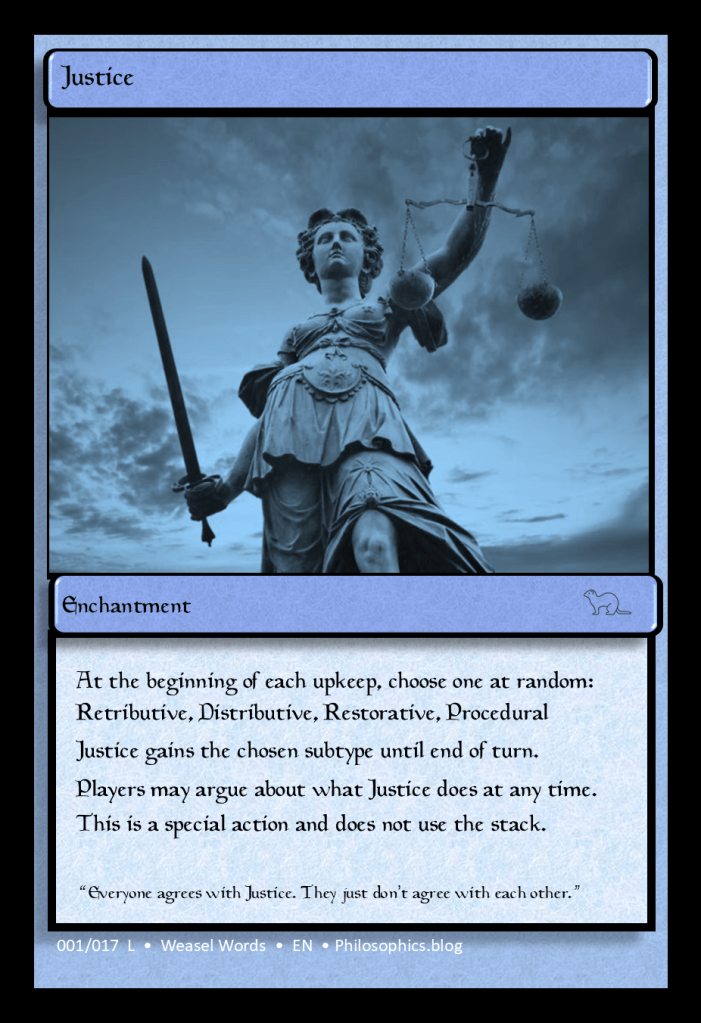

“Justice” is an infamously polysemous term. Retributive, restorative, distributive, procedural, transformative, poetic, cosmic. Pick your flavour. Philosophy departments have been dining out on this buffet for centuries, and nothing useful has come of letting all of them talk at once.

This is precisely where LIH draws a line.

The Language Insufficiency Hypothesis is not interested in pedestrian polysemy — cases where a word has multiple, well-understood meanings that can be disambiguated with minimal friction. That kind of ambiguity is boring. It’s linguistic weather.

What LIH is interested in are terms that appear singular while smuggling incompatible structures. Words that function as load-bearing beams across systems, while quietly changing shape depending on who is speaking and which assumptions are already in play.

“Justice” is one of those words. But it is not usefully analysable in the abstract.

So we pick a single instantiation: Retributive Justice.

Why?

Because retributive justice is the most ontologically demanding and the most culturally entrenched. It requires:

- a persistent self

- a coherent agent

- genuine choice

- intelligible intent

- attributable causation

- commensurable harm

- proportional response

In short, it requires everything to line up.

If justice is going to break anywhere, it will break here.

Retributive justice is therefore not privileged in this model. It is used as a stress test.

The Big Picture: Justice as an Engine, Not a Discovery

The central claim of the model is simple, and predictably unpopular:

Justice is not discovered. It is produced.

Not invented in a vacuum, not hallucinated, not arbitrary — but assembled through a process that takes inputs, applies constraints, and outputs conclusions with an air of inevitability.

The diagram frames retributive justice as an assessment engine.

An engine has:

- inputs

- internal mechanisms

- thresholds

- failure modes

- and outputs

It does not have access to metaphysical truth. It has access to what it has been designed to process.

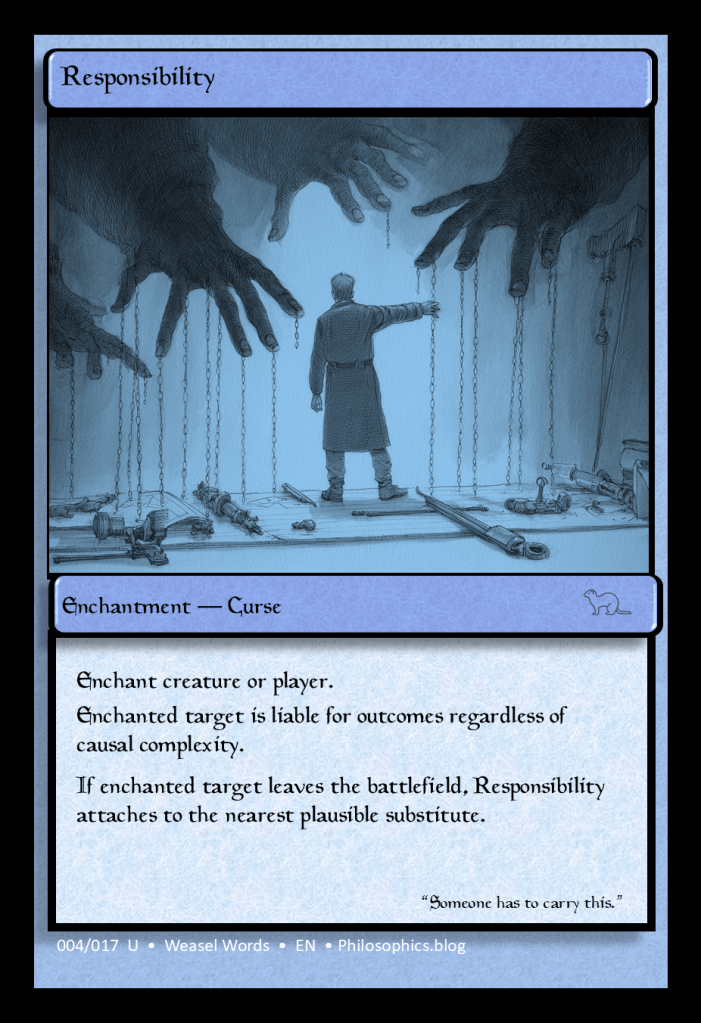

The justice engine takes an encounter — typically an action involving alleged harm — and produces two outputs:

- Desert (what is deserved),

- Responsibility (to whom it is assigned).

Everything else in the diagram exists to make those outputs possible.

The Three Functional Layers

The model is organised into three layers. These are not chronological stages, but logical dependencies. Each layer must already be functioning for the next to make sense.

1. The Constitutive Layer

(What kind of thing a person must already be)

This layer answers questions that are almost never asked explicitly, because asking them destabilises the entire process.

- What counts as a person?

- What kind of self persists over time?

- What qualifies as an agent?

- What does it mean to have agency?

- What is a choice?

- What is intent?

Crucially, these are not empirical discoveries made during assessment. They are asserted ontologies.

The system assumes a particular configuration of selfhood, agency, and intent as a prerequisite for proceeding at all. Alternatives — episodic selves, radically distributed agency, non-volitional action — are not debated. They are excluded.

This is the first “happy path”.

If you do not fit the assumed ontology, you do not get justice. You get sidelined into mitigation, exception, pathology, or incoherence.

2. The Encounter Layer

(What is taken to have happened)

This layer processes the event itself:

- an action

- resulting harm

- causal contribution

- temporal framing

- contextual conditions

- motive (selectively)

This is where the rhetoric of “facts” tends to dominate. But the encounter is never raw. It is already shaped by what the system is capable of seeing.

Causation here is not metaphysical causation. It is legible causation.

Harm is not suffering. It is recognisable harm.

Context is not total circumstance. It is admissible context.

Commensurability acts as a gatekeeper between encounter and evaluation: harms must be made comparable before they can be judged. Anything that resists comparison quietly drops out of the pipeline.

3. The Evaluative Layer

(How judgment is performed)

Only once ontology is assumed and the encounter has been rendered legible does evaluation begin:

- proportionality

- accountability

- normative ethics

- fairness (claimed)

- reasonableness

- bias (usually acknowledged last, if at all)

This layer presents itself as the moral heart of justice. In practice, it is the final formatting pass.

Fairness is not discovered here. It is declared.

Reasonableness does not clarify disputes. It narrows the range of acceptable disagreement.

Bias is not eliminated. It is managed.

At the end of this process, uncertainty is closed.

That closure is the moment justice appears.

Why Disagreement Fails Before It Starts

At this point, dissent looks irrational.

The system has:

- assumed an ontology

- performed an evaluation

- stabilised the narrative through rhetoric

- and produced outputs with institutional authority

To object now is not to disagree about evidence. It is to challenge the ontology that made assessment possible in the first place.

And that is why so many justice debates feel irresolvable.

They are not disagreements within the system.

They are disagreements about which system is being run.

LIH explains why language fails here. The same words — justice, fairness, responsibility, intent — are being used across incompatible ontological commitments. The vocabulary overlaps; the worlds do not.

The engine runs smoothly. It just doesn’t run the same engine for everyone.

Where This Is Going

With the structure in place, we can now do the slower work:

- unpacking individual components

- tracing where ontological choices are asserted rather than argued

- showing how “reasonableness” and “fairness” operate as constraint mechanisms

- and explaining why remediation almost always requires a metaphysical switch, not better rhetoric

Justice is not broken. It is doing exactly what it was built to do.

That should worry us more than if it were merely malfunctioning.

The rest of the story

This essay is already long, so I’m going to stop here.

Not because the interesting parts are finished, but because this is the point at which the analysis stops being descriptive and starts becoming destabilising.

The diagram you’ve just walked through carries a set of suppressed footnotes. They don’t sit at the margins because they’re trivial; they sit there because they are structurally prior. Each one represents an ontological assertion the system quietly requires in order to function at all.

By my count, the model imposes at least five such ontologies. They are not argued for inside the system. They are assumed. They arrive pre-installed, largely because they are indoctrinated, acculturated, and reinforced long before anyone encounters a courtroom, a jury, or a moral dilemma.

Once those ontologies are fixed, the rest of the machinery behaves exactly as designed. Disagreement downstream is permitted; disagreement upstream is not.

In a follow-up essay, I’ll unpack those footnotes one by one: where the forks are, which branch the system selects, and why the alternatives—while often coherent—are rendered unintelligible, irresponsible, or simply “unreasonable” once the engine is in motion.

That’s where justice stops looking inevitable and starts looking parochial.

And that’s also where persuasion quietly gives up.