Fairness, Commensurability, and the Quiet Violence of Comparison

Fairness and Commensurability as Preconditions of Retributive Justice

This is the final part of a 3-part series. Read parts 1 and 2 for a fuller context.

Before the Cards Are Dealt

Two people invoke fairness. They mean opposite things. Both are sincere. Neither can prove the other wrong. This is not a failure of argument. It is fairness working exactly as designed.

Before justice can weigh anything, it must first decide that the things being weighed belong on the same scale. That single move – the assertion that comparison is even possible – quietly does most of the work.

Most people think justice begins at sentencing, or evidence, or procedure. But the real work happens earlier, in a space so normalised it has become invisible. Before any evaluation occurs, the system must install the infrastructure that makes evaluation legible at all.

That infrastructure rests on two foundations:

- fairness, which supplies the rhetoric, and

- commensurability, which supplies the mathematics.

Together, they form the felt beneath the table – the surface on which the cards can be dealt at all.

1. Why Fairness Is Always Claimed, Never Found

Let’s be precise about what fairness is not.

Fairness is not a metric. You cannot measure it, derive it, or point to it in the world.

Fairness is not a principle with determinate content. It generates no specific obligations, no falsifiable predictions, no uniquely correct outcomes.

Fairness is an effect. It appears after assessment, not before it. It is what you call an outcome when you want it to feel inevitable.

Competing Fairness Is Not a Problem

Consider how disputes actually unfold:

- The prosecutor says a long sentence is fair because it is proportional to harm.

- The defender says a shorter sentence is fair because it reflects culpability and circumstance.

- The victim says any sentence is unfair because nothing restores what was taken.

- The community says enforcement itself is unfair because it predictably targets certain groups.

Each claim is sincere. None can be resolved by fairness itself.

That is because fairness has no independent content. It does not decide between these positions. It names them once the system has already decided which will prevail. This is not a bug. It is the feature.

A Fluid Masquerading as an Invariant

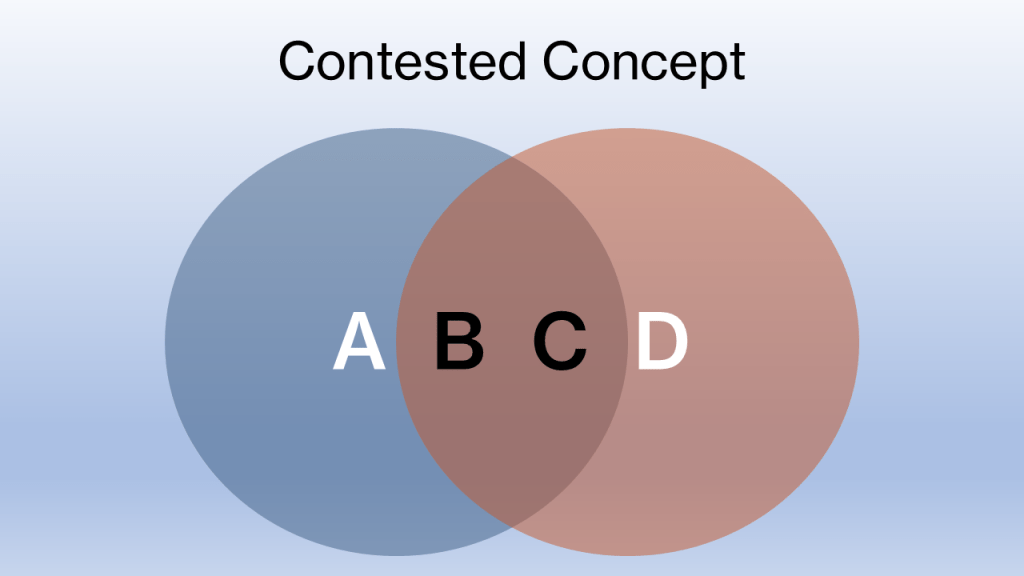

In the language of the Language Insufficiency Hypothesis, fairness is a Fluid – a concept whose boundaries shift with context and use – that masquerades as an Invariant, something stable and observer-independent.

The system treats fairness as perceptual, obvious, discoverable. But every attempt to anchor it collapses into:

- Intuition (‘It just feels right’)

- Precedent (‘This is how we do things’)

- Consensus (‘Most people agree’)

None of these establishes fairness. They merely perform it.

And that performance matters. It converts contested metaphysical commitments into the appearance of shared values. It allows institutions to claim neutrality whilst enforcing specificity. Fairness is what the system says when it wants its outputs to feel unavoidable.

2. The Real Gatekeeper: Commensurability

Fairness does rhetorical work. But it cannot function without something deeper.

That something is commensurability: the assumption that different harms, injuries, and values can be placed on a shared scale and meaningfully compared.

Proportionality presupposes commensurability. Commensurability presupposes an ontology of value. And that ontology is neither neutral nor shared.

When Incommensurability Refuses to Cooperate

A parent loses a child to preventable negligence. A corporation cuts safety corners. A warning is ignored. The system moves. Liability is established. Damages are calculated. £250,000 is awarded.

The parent refuses the settlement. Not because the amount is insufficient. But because money and loss are not the same kind of thing. The judge grows impatient. Lawyers speak of closure. Observers mutter about grief clouding judgment. But this is not grief. It is incommensurability refusing to cooperate.

The parent is rejecting the comparison itself. Accepting payment would validate the idea that a child’s life belongs on a scale with currency. The violence is not the number. It is the conversion. The system cannot process this refusal except as emotional excess or procedural obstruction. Not because it is cruel, but because without commensurability the engine cannot calculate.

Two Ontologies of Value

There are two incompatible ontologies at work here. Only one is playable.

Ontology A: The Scalar Model

- Harm is quantifiable

- Suffering is comparable

- Trade-offs are morally coherent

- Justice is a balancing operation

Under Ontology A, harms differ in degree, not kind. A broken arm, a stolen car, and a dead child all occupy points on the same continuum. This makes proportionality possible.

Ontology B: The Qualitative Model

- Harms are categorical

- Some losses are incommensurable

- Comparison itself distorts

- Justice is interpretive, not calculative

Under Ontology B, harms are different kinds of things. Comparison flattens what matters. To weigh them is to misunderstand them.

Why Only One Ontology Can Play

Retributive justice, as presently constituted, cannot function under Ontology B.

Without scalar values, proportionality collapses. Without comparison, equivalence disappears. Without trade-offs, punishment has no exchange rate.

Ontology B is not defeated. It is disqualified. Structurally, procedurally, rhetorically. The house needs a shared scale. Without it, the game cannot settle accounts.

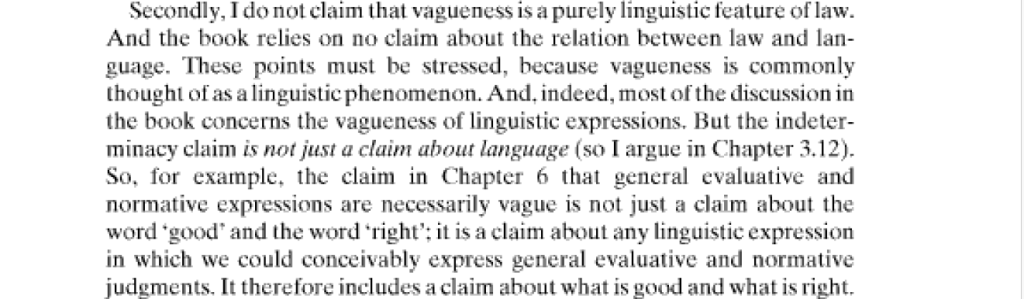

3. Why Incommensurability Is Treated as Bad Faith

Here is where power enters without announcing itself. Incommensurability does not merely complicate disputes. It stalls the engine. And stalled engines threaten institutional legitimacy.

Systems designed to produce closure must ensure that disputes remain within solvable bounds. Incommensurability violates those bounds. It suggests that resolution may be impossible – or that the attempt to resolve does further harm. So the system reframes the problem.

Not as an alternative ontology, but as:

- Unreasonableness

- Extremism

- Emotional volatility

- Refusal to engage in good faith

Reasonableness as Border Control

This is why reasonableness belongs where it does in the model. Not as an evaluative principle, but as a gatekeeping mechanism.

Reasonableness does not assess claims. It determines which claims count as claims at all. This is how commensurability enforces itself without admitting it is doing so. When someone refuses comparison, they are not told their ontology is incompatible with retributive justice. They are told to be realistic.

Ontological disagreement is converted into:

- A tone problem

- A personality defect

- A failure to cooperate

The disagreement is not answered. It is pathologised.

4. Why These Debates Never Resolve

This returns us to the Ontology–Encounter–Evaluation model.

People argue fairness as if adjusting weights would fix the scale. They debate severity, leniency, proportionality.

But when two sides inhabit incompatible ontologies of value, no amount of evidence or dialogue bridges the gap. The real disagreement is upstream.

A prosecutor operating under scalar harm and an advocate operating under incommensurable injury are not disagreeing about facts. They are disagreeing about what kind of thing harm is.

Fairness cannot resolve this, because fairness presupposes the very comparison under dispute. This is why reform debates feel sincere and go nowhere. Outcomes are argued whilst ontological commitments remain invisible.

Remediation Requires Switching Teams

As argued elsewhere, remediation increasingly requires switching teams.

But these are not political teams. They are ontological commitments.

Ontologies are not held like opinions. They are held like grammar. You do not argue someone out of them. At best, you expose their costs. At worst, you force others to operate within yours by disqualifying alternatives.

Retributive justice does the latter.

5. What This Means (Without Offering a Fix)

Justice systems are not broken. They are optimised. They are optimised for closure, manageability, and the appearance of neutrality. Fairness supplies the rhetoric. Commensurability supplies the mathematics. Together, they convert contestable metaphysical wagers into procedural common sense.

That optimisation has costs:

- Disagreements about value become illegible

- Alternative ontologies become unplayable

- Dissent becomes pathology

- Foundations disappear from view

If justice feels fair, it is because the comparisons required to question it were never permitted.

Ontology as Pre-emptive Gatekeeping

None of this requires conspiracy.

Institutions do not consciously enforce ontologies. They do not need to.

They educate them. Normalise them. Proceduralise them. Then treat their rejection as irrationality.

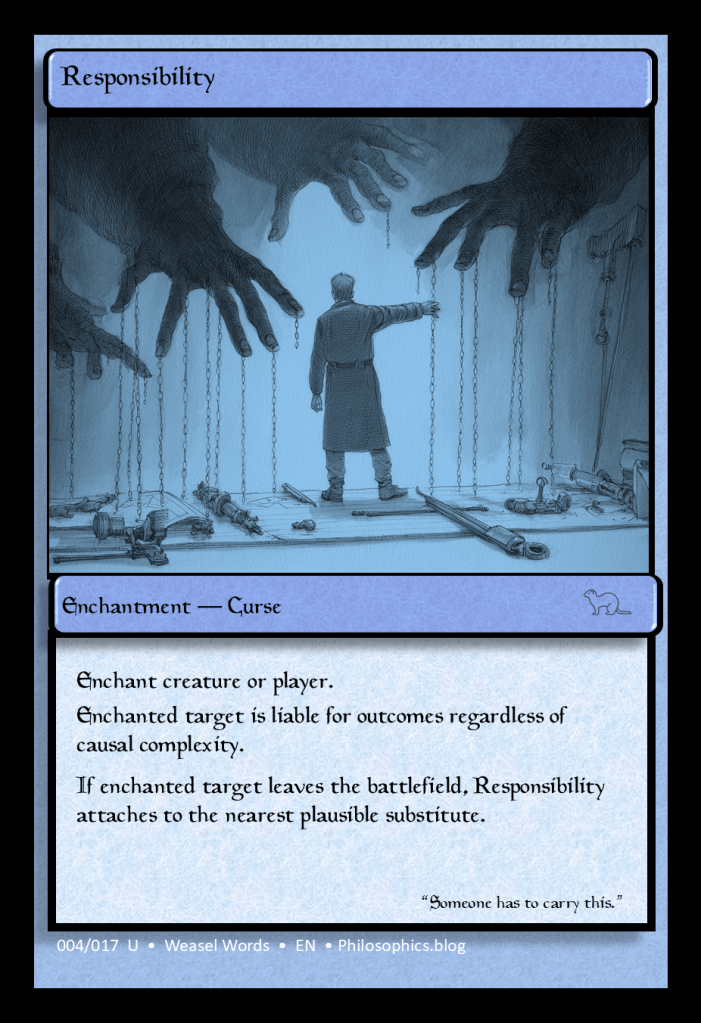

By the time justice is invoked, the following have already been installed as reality:

- That persons persist over time in morally relevant ways

- That agents meaningfully choose under conditions that count

- That harms can be compared and offset

- That responsibility can be localised

- That disagreement beyond a point is unreasonable

None of these are discovered. All are rehearsed.

A law student learns that ‘the reasonable person’ is a construct. By year three, they use it fluently. It no longer feels constructed.

This is not indoctrination. It is fluency.

And fluency is how ontologies hide.

By the time an alternative appears – episodic selfhood, incommensurable harm, distributed agency – it does not look like metaphysics. It looks like confusion.

Rationality as Border Control

The system does not say: we reject your ontology.

It says: that’s not how the world works.

Or worse: you’re being unreasonable.

Ontological disagreement is reframed as a defect in the person. And defects do not need answers. They need management.

This is why some arguments feel impossible to have. One ontology has been naturalised into common sense. The other has been reclassified as error.

The Final Irony

The more fragile the foundations, the more aggressively they must be defended as self-evident.

- Free will is taught as obvious.

- Fairness is invoked as perceptual.

- Responsibility is treated as observable.

- Incommensurability is treated as sabotage.

Not because the system is confident.

Because it cannot afford not to be.

The Point

Justice does not merely rely on asserted ontologies. It expends enormous effort ensuring they never appear asserted at all.

By the time the cards are dealt, the rules have already been mistaken for reality. That is the felt beneath the table. Invisible. Essential. Doing all the work. And if you want to challenge justice meaningfully, you do not start with outcomes. You start by asking:

What comparisons are we being asked to accept as natural? And what happens to those who refuse?

Most people never make that move. Not because it is wrong. But because by the time you notice the game is rigged, you are already fluent in its rules. And fluency feels like truth.

Final Word

Why write these assessments? Why care?

With casinos, like cricket, we understand something fundamental: these are games. We can learn the rules. We can decide whether to play. We can walk away.

Justice is different. Justice is not opt-in. It is imposed. You do not get to negotiate the rules, the scoring system, or the house assumptions about what counts as a move. Once you are inside, even dissent must be expressed in the system’s own grammar. Appeals do not question the game; they replay it under slightly altered conditions.

You may contest the outcome. You may plead for leniency. You may argue fairness. You may not ask why chips are interchangeable with lives, why losses must be comparable, or why refusing comparison itself counts as misconduct.

Imagine being forced into a casino. Forced to play. Forced to stake things you do not believe are wagerable. Then told, when you object, that the problem is not the game, but your attitude toward it.

That is why these assessments matter. Not to declare justice illegitimate. Not to offer a fix. But to make visible the rules that pretend not to be rules at all. Because once you mistake fluency for truth, the house no longer needs to rig the game.

You will do it for them.