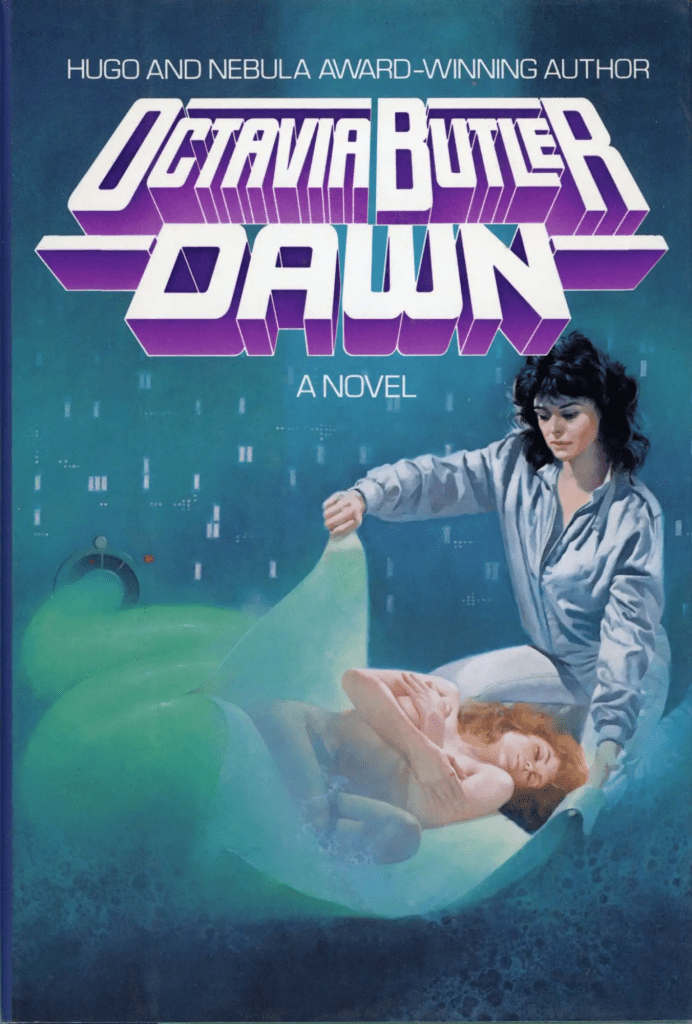

I’ve been reading Octavia Butler’s Dawn and find myself restless. The book is often lauded as a classic of feminist science fiction, but I struggle with it. My problem isn’t with aliens, or even with science fiction tropes; it’s with the form itself, the Modernist project embedded in the genre, which insists on posing questions and then supplying answers, like a catechism for progress. Sci-Fi rarely leaves ambiguity alone; it instructs.

Find the companion piece on my Ridley Park blog.

Beauvoir’s Ground

Simone de Beauvoir understood “woman” as the Other – defined in relation to men, consigned to roles of reproduction, care, and passivity. Her point was not that these roles were natural, but that they were imposed, and that liberation required stripping them away.

Octavia Butler’s Lilith

Lilith Iyapo, the protagonist of Dawn, should be radical. She is the first human awakened after Earth’s destruction, a Black woman given the impossible role of mediating between humans and aliens. Yet she is not allowed to resist her role so much as to embody it. She becomes the dutiful mother, the reluctant carer, the compliant negotiator. Butler’s narration frequently tells us what Lilith thinks and feels, as though to pre-empt the reader’s interpretation. She is less a character than an archetype: the “reasonable woman,” performing the script of liberal Western femininity circa the 1980s.

Judith Butler’s Lens

Judith Butler would have a field day with this. For her, gender is performative: not an essence but a repetition of norms. Agency, in her view, is never sovereign; it emerges, if at all, in the slippages of those repetitions. Read through this lens, Octavia Butler’s Lilith is not destabilising gender; she is repeating it almost too faithfully. The novel makes her into an allegory, a vessel for explaining and reassuring. She performs the role assigned and is praised for her compliance – which is precisely how power inscribes itself.

Why Sci-Fi Leaves Me Cold

This helps me understand why science fiction so often fails to resonate with me. The problem isn’t the speculative element; I like the idea of estrangement, of encountering the alien. The problem is the Modernist scaffolding that underwrites so much of the genre: the drive to solve problems, to instruct the reader, to present archetypes as universal stand-ins. I don’t identify with that project. I prefer literature that unsettles rather than reassures, that leaves questions open rather than connecting the dots.

So, Butler versus Butler on the bedrock of Beauvoir: one Butler scripting a woman into an archetype, another Butler reminding us that archetypes are scripts. And me, somewhere between them, realising that my discomfort with Dawn is not just with the book but with a genre that still carries the DNA of the very Modernism it sometimes claims to resist.