I was having an inappropriate chat with ChatGPT and, per Feyerabend, I once again discovered that some of the best inspirations are unplanned. The conversation circled around to the conflicting narratives of Erasmus and Wells. Enter, Plato, McGilchrist, and the Enlightenment – all living rent-free in my head – and I end up with this.

I. The Proverb and Its Presumption

Erasmus sits at his writing desk in 1500-something, cheerful as a man who has never once questioned the premises of his own eyesight, and pens what will become one of the West’s most durable little myths: ‘In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king’. It arrives packaged as folk wisdom, the sort of thing you’re meant to nod at sagely over a pint. And for centuries, we did. The proverb became shorthand for a comfortable fantasy: that advantage is advantage everywhere, that perception grants sovereignty, that a man with superior faculties will naturally ascend to his rightful place atop whatever heap he finds himself on.

In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king

– Erasmus

It’s an Enlightenment dream avant la lettre, really – this breezy confidence that reason, sight, knowledge, insight will simply work wherever they’re deployed. The one-eyed man doesn’t need to negotiate with the blind. He doesn’t need their endorsement, their customs, their consent. He arrives, he sees, he rules. The proverb presumes a kind of metaphysical meritocracy, where truth and capability are self-authenticating, where the world politely arranges itself around whoever happens to possess the sharper tools.

It’s the intellectual equivalent of showing up in a foreign country with a briefcase full of sterling and expecting everyone to genuflect. And like most folk wisdom, it survives because it flatters us. It tells us that our advantages – our rationality, our education, our painstakingly cultivated discernment – are universally bankable. That we, the seeing, need only arrive for the blind to recognise our superiority.

Erasmus offers this with no apparent irony. He hands us a proverb that whispers: your clarity is your crown.

II. Wells Wanders In

Four centuries later, H.G. Wells picks up the proverb, turns it over in his hands like a curious stone, and proceeds to detonate it.

The Country of the Blind (1904) is many things – a fable, a thought experiment, a sly dismantling of Enlightenment presumption – but above all it is an act of literary vandalism against Erasmus and everything his proverb smuggles into our collective assumptions. Wells sends his protagonist, Nuñez, tumbling into an isolated Andean valley where a disease has rendered the entire population blind for generations. They’ve adapted. They’ve built a culture, a cosmology, a complete lifeworld organised around their particular sensorium. Sight isn’t absent from their world; it’s irrelevant. Worse: it’s nonsense. The seeing man’s reports of ‘light’ and ‘sky’ and ‘mountains’ sound like the ravings of a lunatic.

Nuñez arrives expecting Erasmus’s kingdom. He gets a psychiatric evaluation instead.

The brilliance of Wells’s story isn’t simply that the one-eyed man fails to become king – it’s how he fails. Nuñez doesn’t lack effort or eloquence. He tries reason, demonstration, patient explanation. He attempts to prove the utility of sight by predicting sunrise, by describing distant objects, by leveraging his supposed advantage. None of it matters. The blind don’t need his reports. They navigate their world perfectly well without them. His sight isn’t superior; it’s alien. And in a culture that has no use for it, no linguistic scaffolding to accommodate it, no social structure that values it, his one eye might as well be a vestigial tail.

The valley’s elders eventually diagnose Nuñez’s problem: his eyes are diseased organs that fill his brain with hallucinations. The cure? Surgical removal.

Wells lets this hang in the air, brutal and comic. The one-eyed man isn’t king. He’s a patient. And if he wants to stay, if he wants to belong, if he wants to marry the girl he’s fallen for and build a life in this place, he’ll need to surrender the very faculty he imagined made him superior. He’ll need to let them fix him.

The story ends ambiguously – Nuñez flees at the last moment, stumbling back toward the world of the sighted, though whether he survives is left unclear. But the damage is done. Erasmus’s proverb lies in ruins. Wells has exposed its central presumption: that advantage is advantage everywhere. That perception grants authority. That reason, clarity, and superior faculties are self-evidently sovereign.

They’re not. They’re only sovereign where the culture already endorses them.

III. Plato’s Ghost in the Valley

If Wells dismantles Erasmus, Plato hovers over the whole scene like a weary ghost, half scolding, half despairing, muttering that he told us this would happen.

The Allegory of the Cave, after all, is the original version of this story. The philosopher escapes the cave, sees the sun, comprehends the Forms, and returns to liberate his fellow prisoners with reports of a luminous reality beyond the shadows. They don’t thank him. They don’t listen. They think he’s mad, or dangerous, or both. And if he persists – if he tries to drag them toward the exit, toward the light they can’t yet see – they’ll kill him for it.

Plato’s parable is usually read as a tragedy of ignorance: the prisoners are too stupid, too comfortable, too corrupted by their chains to recognise truth when it’s offered. But read it alongside Wells and the emphasis shifts. The cave-dwellers aren’t wrong, exactly. They’re coherent. They’ve built an entire epistemology around shadows. They have experts in shadow interpretation, a whole language for describing shadow behaviour, social hierarchies based on shadow-predicting prowess. The philosopher returns with reports of a three-dimensional world and they hear gibberish. Not because they’re defective, but because his truth has no purchase in their lifeworld.

Plato despairs over this. He wants the prisoners to want liberation. He wants truth to be self-authenticating, wants knowledge to compel assent simply by virtue of being knowledge. But the cave doesn’t work that way. The prisoners don’t want truth; they want comfort shaped like reality. They want coherence within the system they already inhabit. The philosopher’s sun is as alien to them as Nuñez’s sight is to the blind valley.

And here’s the kicker: Plato knows this. That’s why the allegory is tragic rather than triumphant. The philosopher does see the sun. He does apprehend the Forms. But his knowledge is useless in the cave. Worse than useless – it makes him a pariah, a madman, a threat. His enlightenment doesn’t grant him sovereignty; it exile him from the only community he has.

The one-eyed man isn’t king. He’s the lunatic they’ll string up if he doesn’t learn to shut up about the sky.

IV. The Enlightenment’s Magnificent Blunder

Once you’ve got Erasmus, Wells, and Plato in the same room, the Enlightenment’s central fantasy collapses like wet cardboard.

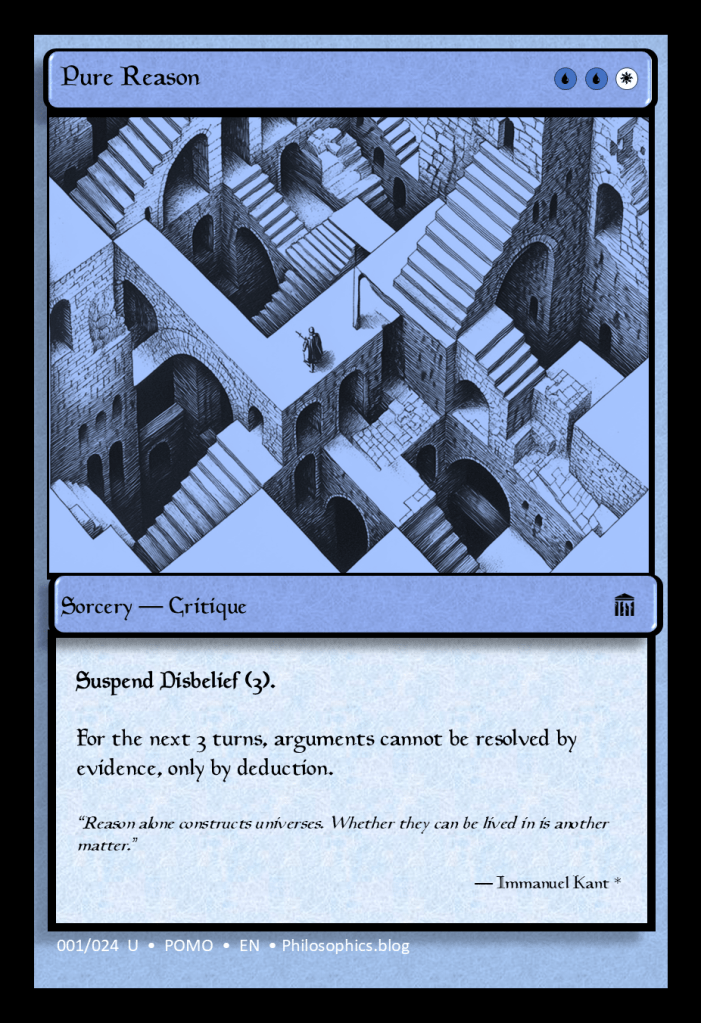

Humanity’s great Enlightenment wheeze – that baroque fantasy of Reason marching triumphantly through history like a powdered dragoon – has always struck me as the intellectual equivalent of selling snake oil in a crystal decanter. We were promised lucidity, emancipation, and the taming of ignorance; what we got was a fetish for procedural cleverness, a bureaucratisation of truth, and the ghastly belief that if you shine a bright enough torch into the void, the void will politely disclose its contents.

The Enlightenment presumed universality. It imagined that rationality, properly deployed, would work everywhere – that its methods were culture-neutral, that its conclusions were binding on all reasonable minds, that the shadows in Plato’s cave and the blindness in Wells’s valley could be cured by the application of sufficient light and logic. It treated reason as a kind of metaphysical bulldozer, capable of flattening any terrain it encountered and paving the way for Progress, Truth, and Universal Human Flourishing.

This was, to put it mildly, optimistic.

What the Enlightenment missed – what Erasmus’s proverb cheerfully ignores and what Wells’s story ruthlessly exposes – is that rationality is parochial. It’s not a universal solvent. It’s a local dialect, a set of practices that evolved within particular cultures, buttressed by particular institutions, serving particular ends. The Enlightenment’s rationality is Western rationality, Enlightenment rationality, rationality as understood by a specific cadre of 18th-century European men who happened to have the printing press, the political clout, and the colonial apparatus to export their epistemology at gunpoint.

They mistook their own seeing for sight itself. They mistook their own lifeworld for the world. And they built an entire civilisational project on the presumption that everyone else was just a less-developed version of them – prisoners in a cave, blind villagers, savages waiting to be enlightened.

The one-eyed man imagined himself king. He was actually the emissary who forgot to bow.

V. McGilchrist’s Neuroscientific Millinery

Iain McGilchrist sits in the same intellectual gravity well as Plato and Wells, only he dresses his thesis up in neuroscientific millinery so contemporary readers don’t bolt for the door. The Master and His Emissary is essentially a 500-page retelling of the same ancient drama: the emissary – our little Enlightenment mascot – becomes so enamoured of his own procedures, abstractions, and tidy schemas that he forgets the Master’s deeper, embodied, culturally embedded sense-making.

McGilchrist’s parable is neurological rather than allegorical, but the structure is identical. The left hemisphere (the emissary) excels at narrow focus, manipulation, abstraction – the sort of thing you need to count coins or parse grammar or build bureaucracies. The right hemisphere (the Master) handles context, pattern recognition, relational understanding – the sort of thing you need to navigate an actual lifeworld where meaning is messy, embodied, and irreducible to procedures.

The emissary is supposed to serve the Master. Left-brain proceduralism is supposed to be a tool deployed within the broader, contextual sense-making of the right brain. But somewhere along the way – roughly around the Enlightenment, McGilchrist suggests – the emissary convinced itself it could run the show. Left-brain rationality declared independence from right-brain contextuality, built an empire of abstraction, and wondered why the world suddenly felt thin, schizophrenic, oddly two-dimensional.

It’s Erasmus all over again: the presumption that the emissary with one eye should be king. The same tragic misunderstanding of how worlds cohere.

McGilchrist’s diagnosis is clinical, but his conclusion is damning. Western modernity, he argues, has become pathologically left-hemisphere dominant. We’ve let analytic thought pretend it’s sovereign. We’ve mistaken our schemas for reality, our maps for territory, our procedures for wisdom. We’ve built cultures that privilege manipulation over meaning, extraction over relationship, clarity over truth. And we’re baffled when these cultures feel alienating, when they produce populations that are anxious, depressed, disenchanted, starved for something they can’t quite name.

The emissary has forgotten the Master entirely. And the Master, McGilchrist suggests, is too polite – or too injured – to stage a coup.

In McGilchrist’s frame, culture is the Master. Strategy, reason, Enlightenment rationality – these are the emissary’s tools. Useful, necessary even, but never meant to govern. The Enlightenment’s mistake was letting the emissary believe his tools were all there was. It’s the same delusion Nuñez carries into Wells’s valley: the belief that sight, reason, superior faculties are enough. That the world will rearrange itself around whoever shows up with the sharper implements.

It won’t. The valley doesn’t need your eyes. The cave doesn’t want your sun. And the Master doesn’t answer to the emissary’s paperwork.

VI. The Triumph of Context Over Cleverness

So here’s what these three – Erasmus, Wells, Plato – triangulate, and what McGilchrist confirms with his neuroscientific gloss: the Enlightenment dream was always a category error.

Reason doesn’t grant sovereignty. Perception doesn’t compel assent. Superior faculties don’t self-authenticate. These things only work – only mean anything, only confer any advantage – within cultures that already recognise and value them. Outside those contexts, they’re noise. Gibberish. Hallucinations requiring surgical intervention.

The one-eyed man arrives in the land of the blind expecting a kingdom. What he gets is a reminder that kingdoms aren’t built on faculties; they’re built on consensus. On shared stories, shared practices, shared ways of being-in-the-world. Culture is the bedrock. Reason is just a tool some cultures happen to valorise.

And here’s the uncomfortable corollary: if reason is parochial, if rationality is just another local dialect, then the Enlightenment’s grand project – its universalising ambitions, its colonial export of Western epistemology, its presumption that everyone, everywhere, should think like 18th-century European philosophes – was always a kind of imperialism. A metaphysical land-grab dressed up in the language of liberation.

The Enlightenment promised illumination but delivered a blinding glare that obscures more than it reveals. It told us the cave was a prison and the valley was backward and anyone who didn’t see the world our way was defective, uncivilised, in need of correction. It never occurred to the Enlightenment that maybe – just maybe – other cultures had their own Masters, their own forms of contextual sense-making, their own ways of navigating the world that didn’t require our light.

Wells understood this. Plato suspected it. McGilchrist diagnoses it. And Erasmus, bless him, never saw it coming.

VII. The Enlightenment’s Paper Crown

The Enlightenment liked to imagine itself as the adult entering the room, flicking on the light-switch, and announcing that, at long last, the shadows could stop confusing the furniture for metaphysics. This is the kind of confidence you only get when your culture hasn’t yet learned the words for its own blind spots. It built an entire worldview on the hopeful presumption that its preferred modes of knowing weren’t just one way of slicing experience, but the gold standard against which all other sense-making should be judged.

Call it what it is: a provincial dialect masquerading as the universal tongue. A parochial habit dressed in imperial robes. The Enlightenment always smelled faintly of a man who assumes everyone else at the dinner table will be impressed by his Latin quotations. And when they aren’t, he blames the table.

The deeper farce is that Enlightenment rationality actually believed its tools were transferrable. That clarity is clarity everywhere. That if you wheel enough syllogisms into a space, the locals will drop their incense and convert on sight. Wells disabuses us of this; Plato sighs that he tried; McGilchrist clinically confirms the diagnosis. The emissary, armed with maps and measuring sticks, struts into the valley expecting coronation and is shocked – genuinely shocked – to discover that nobody particularly cares for his diagrams.

The Enlightenment mistake wasn’t arrogance (though it had that in liberal supply). It was context-blindness. It thought procedures could substitute for culture. It thought method could replace meaning. It thought mastery was a matter of getting the right answer rather than belonging to the right world.

You can all but hear the emissary stamping his foot.

VIII. The Anti-Enlightenment Position (Such as It Is)

My own stance is drearily simple: I don’t buy the Enlightenment’s sales pitch. Never have. The promise of universal reason was always a conjuring trick designed to flatter its adherents into thinking that their habits were Nature’s preferences. Once you stop confusing methodological neatness with metaphysical authority, the entire apparatus looks less like a cathedral of light and more like a filing system that got ideas above its station.

The problem isn’t that reason is useless. The problem is that reason imagines itself sovereign. Reason is a brilliant servant, a competent emissary, and an atrocious king. Culture is the king; context is the kingdom. Without those, rationality is just an embarrassed bureaucrat looking for a desk to hide behind.

This is why I keep banging on about language insufficiency, parochial cognition, and the delightful way our concepts disintegrate once you wander too far from the lifeworlds that birthed them. The Enlightenment thought the human mind was a searchlight. It’s closer to a candle in a draughty hall. You can still get work done with a candle. You just shouldn’t be telling people it can illuminate the universe.

So the anti-Enlightenment move isn’t a call to smash the instruments. It’s a call to read the room. To stop pretending the emissary is the Master. To stop assuming sight is a passport to sovereignty. To stop wandering into other cultures – other caves, other valleys, other hemispheres – with a ruler and a smirk, convinced you’re about to be crowned.

Underneath these brittle idols lies the far messier truth that cognition is parochial, language insufficient, and ‘rationality’ a parlour trick we perform to impress ourselves. I’m not proposing a new catechism, nor am I pining for some prelapsarian alternative. I’m simply pointing out that the Enlightenment promised illumination but delivered a blinding glare that obscures more than it reveals.

The task, then, is to grow comfortable with the dimness. To navigate by flicker rather than floodlight. To admit that the world was never waiting to be made ‘clear’ in the first place.

This doesn’t mean abandoning reason. It means remembering that reason is the emissary, not the Master. It means recognising that our schemas are provisional, our maps incomplete, our procedures useful only within the cultures that endorse them. It means learning to bow – to culture, to context, to the irreducible messiness of lifeworlds we don’t fully understand and can’t procedurally master.

The one-eyed man never was king. At best, he was an enthusiastic tourist with a very noisy torch. The sooner he stops shining it into other people’s faces, the sooner we can get on with the far more interesting business of navigating a world that never promised to be legible.

Not a kingdom of sight. Just a world where the emissary remembers his place.