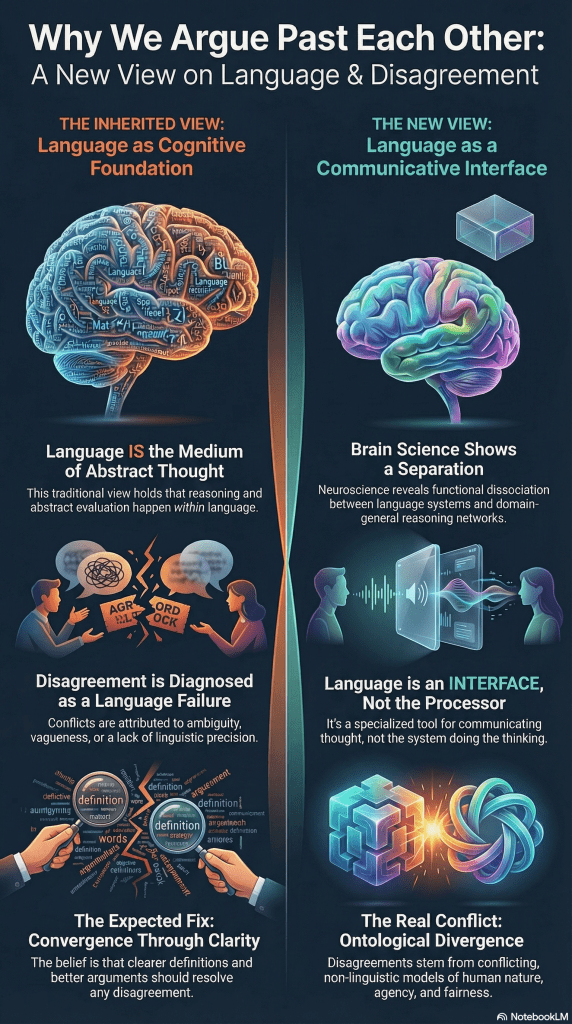

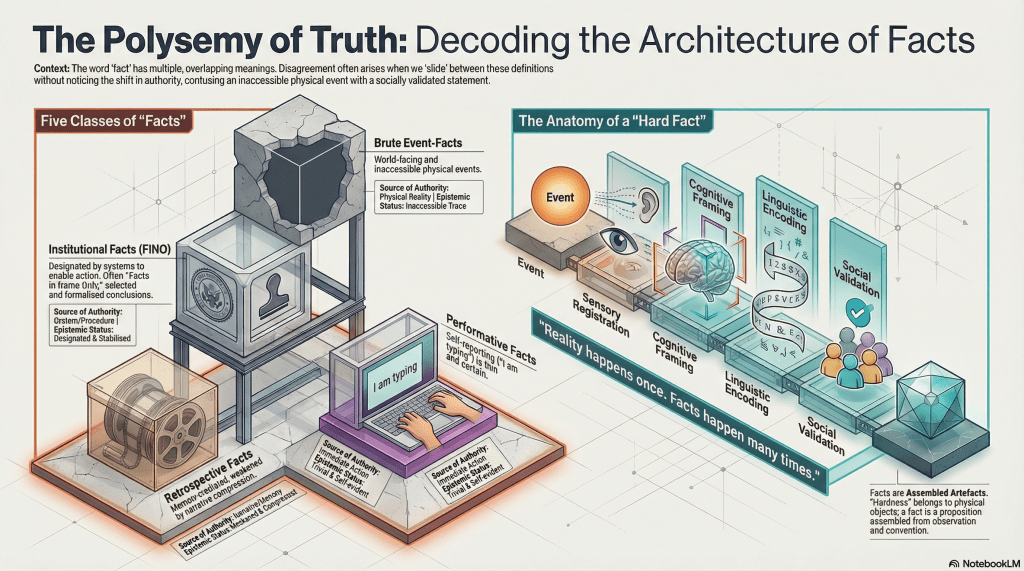

I want to clarify my recent The Trouble with Facts post. I realise that I was speaking to one non-trivial form of facts, but there is more than one class of facts. We argue about facts as if the word named a single, stable thing. It doesn’t. It names a family of very different things, quietly grouped together by habit, convenience, and institutional need. Most disputes about facts go nowhere, not because one side is irrational, but because the word itself is doing covert work. We slide between meanings without noticing, then act surprised when disagreement follows. This piece is an attempt to slow that slide.

Polysemy We Notice, Polysemy We Don’t

We are comfortable with ambiguity when it is obvious. A bank can be a financial institution or the edge of a river. A bat can be an animal or a piece of sports equipment. Context resolves these instantly. No one feels existentially threatened by the ambiguity.

Fact is different. The word is polysemous in a way that is both subtle and consequential. Its meanings sit close enough to bleed into one another, allowing certainty from one sense to be smuggled into another without detection. Calling something a fact does not merely describe it. It confers authority. It signals that questioning should stop. That is why this ambiguity matters.

Different Kinds of Facts

Before critiquing facts, we need to sort them.

1. Event-facts (brute, world-facing)

As mentioned previously, these concern what happens in the world, independent of observation.

- A car collides with a tree.

- Momentum changes.

- Metal deforms.

These events occur whether or not anyone notices them. They are ontologically robust and epistemically inaccessible. No one ever encounters them directly. We only ever encounter traces.

2. Indexical or performative facts (trivial, self-reporting)

“I am typing.”

I am doing this now – those now may not be relevant when you read this. This is a fact, but a very thin one. Its authority comes from the coincidence of saying and doing. It requires no reconstruction, no inference, no institutional validation. These facts are easy because they do almost no work.

3. Retrospective personal facts (memory-mediated)

“I was typing.”

This may be relevant now, at least relative to the typing of this particular post. Still a fact, but weaker. Memory enters. Narrative compression enters. Selectivity enters. The same activity now carries a different epistemic status purely because time has passed.

4. Prospective statements (modal, not yet facts)

“I will be typing.”

This is not yet a fact. It may never come to be one. It is an intention or prediction that may or may not be realised. Future-tense claims are often treated as incipient facts, but this is a category error with real consequences.

5. Institutional facts (designated, procedural)

“The court finds…”

“The report concludes…”

These are facts by designation. They are not discovered so much as selected, formalised, and stabilised so that systems can act. They are unlikely to rise to the level of facts, so the legal system tends to generate facts in name only – FINO, if I am being cute.

All of these are called ‘facts’. They are not interchangeable. The trouble begins when certainty migrates illicitly from trivial or institutional facts into brute event-facts, and we pretend nothing happened in the transfer.

One Motor Vehicle

Reconsider the deliberately simple case: A motor vehicle collides with a tree. Trees are immobile, so we can rule out the tree colliding with the car.

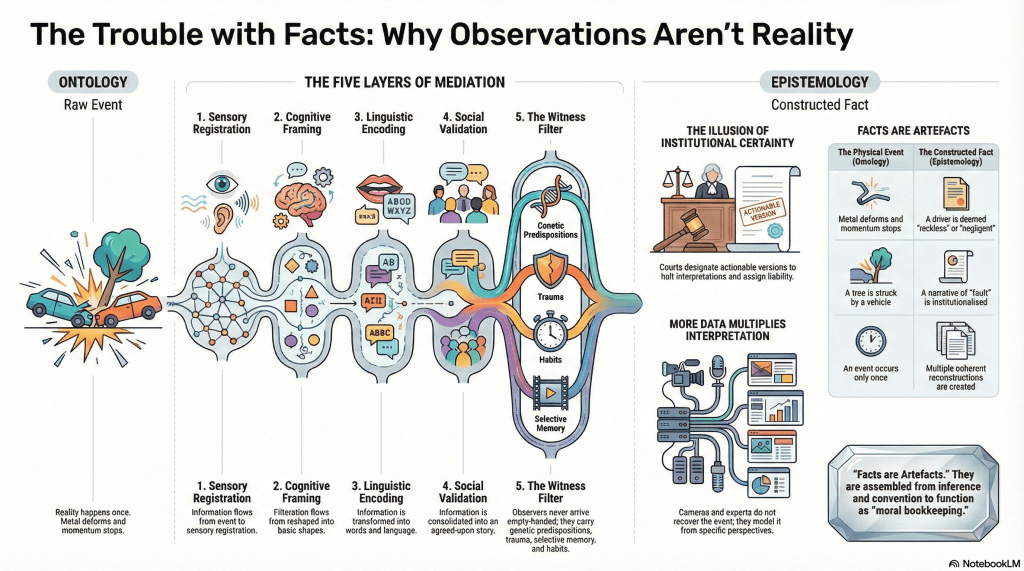

Ontologically, something happened. Reality did not hesitate. But even here, no one has direct access to the event itself.

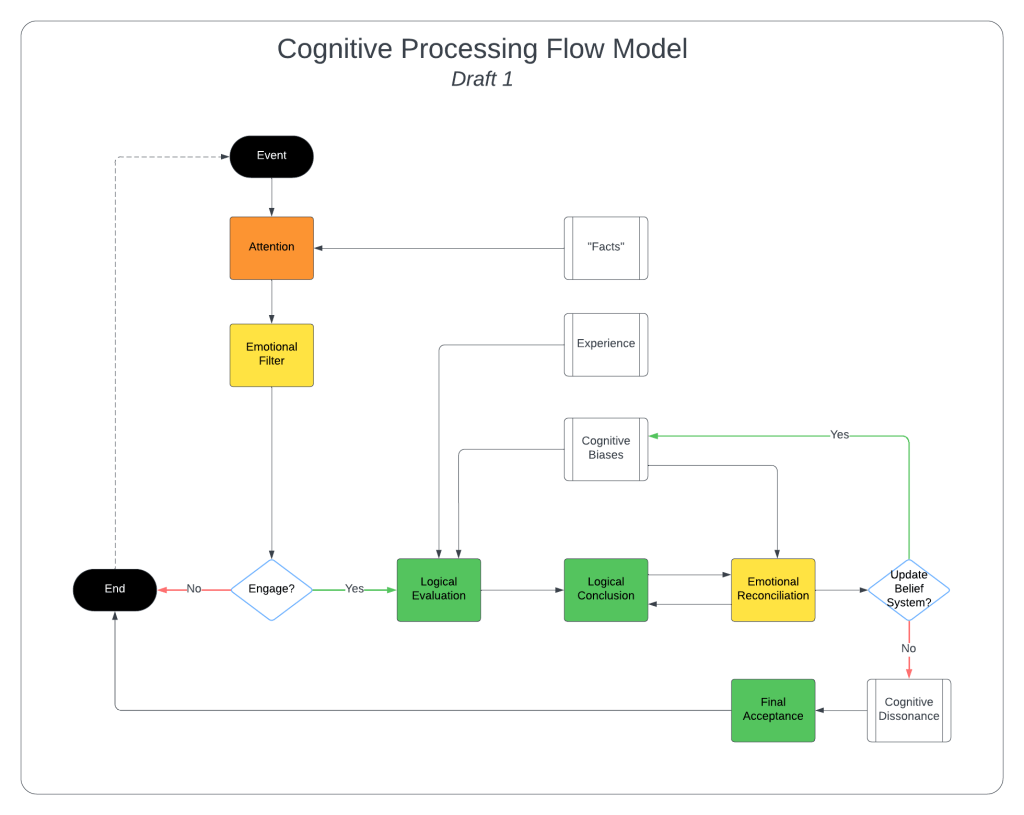

The driver does not enjoy privileged access. They experience shock, adrenaline, attentional narrowing, selective memory, post hoc rationalisation, perhaps a concussion. Already several layers intervene before language even arrives.

A rough schema looks like this:

event → sensory registration → cognitive framing → linguistic encoding → social validation

Ontology concerns what happens.

Epistemology concerns how anything becomes assertable.

Modern thinking collapses the second into the first and calls the result the facts.

People speak of “hard facts” as if hardness transfers from objects to propositions by proximity. It doesn’t. The tree is solid. The fact is an artefact assembled from observation, inference, convention, and agreement.

And so it goes…

Why the Confusion Persists

When someone responds, “But isn’t it a fact that I read this?”, the answer is yes. A different kind of fact.

The error lies not in affirming facts, but in failing to distinguish them. The word fact allows certainty to migrate across categories unnoticed, from trivial self-reports to brute world-events, and from institutional verdicts to metaphysical claims. That migration is doing the work.

Conclusion

Clarifying types of facts does not weaken truth. It prevents us from laundering certainty where it does not belong.

Facts exist. Events occur. But they do not arrive unmediated, innocent, or singular.

Reality happens once. Facts happen many times.

The mistake was never that facts are unreal. It was believing they were all the same kind of thing.