—On Epistemology, Pop Psychology, and the Cult of Empirical Pretence

Science, we’re told, is the beacon in the fog – a gleaming lighthouse of reason guiding us through the turbulent seas of superstition and ignorance. But peer a bit closer, and the lens is cracked, the bulb flickers, and the so-called lighthouse keeper is just some bloke on TikTok shouting about gut flora and intermittent fasting.

We are creatures of pattern. We impose order. We mistake correlation for causation, narrative for truth, confidence for knowledge. What we have, in polite academic parlance, is an epistemology problem. What we call science is often less Newton and more Nostradamus—albeit wearing a lab coat and wielding a p-hacked dataset.

Let’s start with the low-hanging fruit—the rotting mango of modern inquiry: nutritional science, which is to actual science what alchemy is to chemistry, or vibes are to calculus. We study food the way 13th-century monks studied demons: through superstition, confirmation bias, and deeply committed guesswork. Eat fat, don’t eat fat. Eat eggs, don’t eat eggs. Eat only between the hours of 10:00 and 14:00 under a waxing moon while humming in Lydian mode. It’s a cargo cult with chia seeds.

But why stop there? Let’s put the whole scientific-industrial complex on the slab.

Psychology: The Empirical Astrological Society

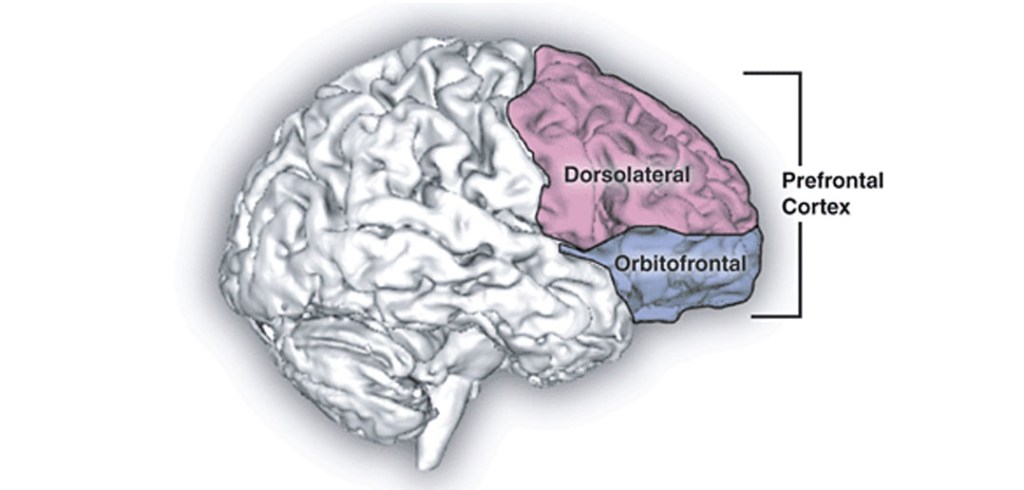

Psychology likes to think it’s scientific. Peer-reviewed journals, statistical models, the odd brain scan tossed in for gravitas. But at heart, much of it is pop divination, sugar-dusted for mass consumption. The replication crisis didn’t merely reveal cracks – it bulldozed entire fields. The Stanford Prison Experiment? A theatrical farce. Power poses? Empty gestural theatre. Half of what you read in Psychology Today could be replaced with horoscopes and no one would notice.

Medical Science: Bloodletting, But With Better Branding

Now onto medicine, that other sacred cow. We tend to imagine it as precise, data-driven, evidence-based. In practice? It’s a Byzantine fusion of guesswork, insurance forms, and pharmaceutical lobbying. As Crémieux rightly implies, medicine’s predictive power is deeply compromised by overfitting, statistical fog, and a staggering dependence on non-replicable clinical studies, many funded by those who stand to profit from the result.

And don’t get me started on epidemiology, that modern priesthood that speaks in incantations of “relative risk” and “confidence intervals” while changing the commandments every fortnight. If nutrition is theology, epidemiology is exegesis.

The Reproducibility Farce

Let us not forget the gleaming ideal: reproducibility, that cornerstone of Enlightenment confidence. The trouble is, in field after field—from economics to cancer biology—reproducibility is more aspiration than reality. What we actually get is a cacophony of studies no one bothers to repeat, published to pad CVs, p-hacked into publishable shape, and then cited into canonical status. It’s knowledge by momentum. We don’t understand the world. We just retweet it.

What, Then, Is To Be Done?

Should we become mystics? Take up tarot and goat sacrifice? Not necessarily. But we should strip science of its papal robes. We should stop mistaking publication for truth, consensus for accuracy, and method for epistemic sanctity. The scientific method is not the problem. The pretence that it’s constantly being followed is.

Perhaps knowledge doesn’t have a half-life because of progress, but because it was never alive to begin with. We are not disproving truth; we are watching fictions expire.

Closing Jab

Next time someone says “trust the science,” ask them: which bit? The part that told us margarine was manna? The part that thought ulcers were psychosomatic? The part that still can’t explain consciousness, but is confident about your breakfast?

Science is a toolkit. But too often, it’s treated like scripture. And we? We’re just trying to lose weight while clinging to whatever gospel lets us eat more cheese.