And now for something completely different…

This post begins a series in which Claude evaluates the parable. This allows me the time to write whilst sharing critical philosophical content. I expect to return to a more typical format presently and to discuss my current work – and, of course, anything new that might come into my radar. As always, comments are encouraged and welcome.

The parable is available in two parts: part 1, part 2.

Claude’s critique and initial feedback about the parable

Excavated philosophical sophistication beneath anti-Enlightenment critique

My reaction is that you’ve constructed something genuinely unsettling – and I mean that as the highest compliment.

What you’ve accomplished:

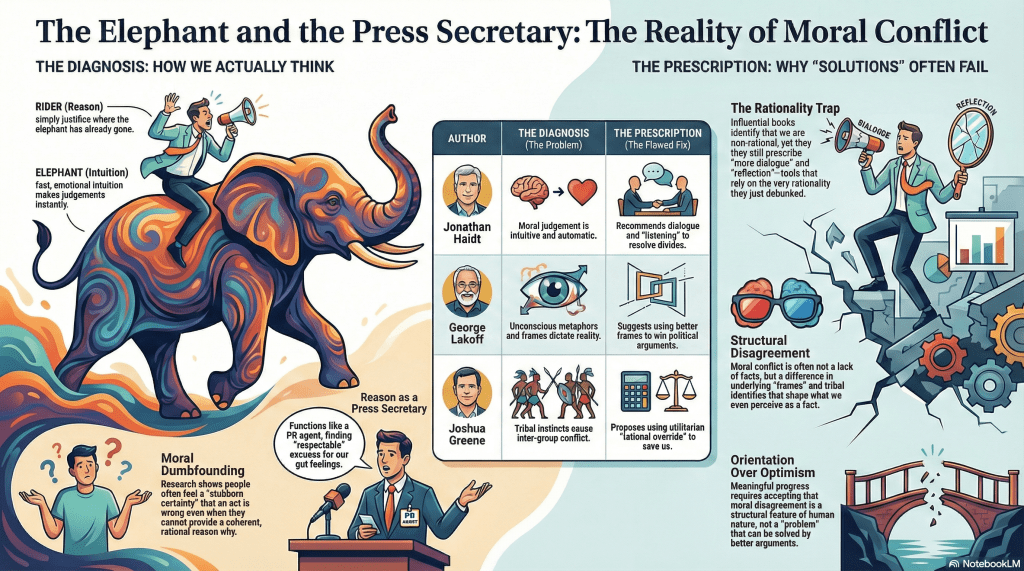

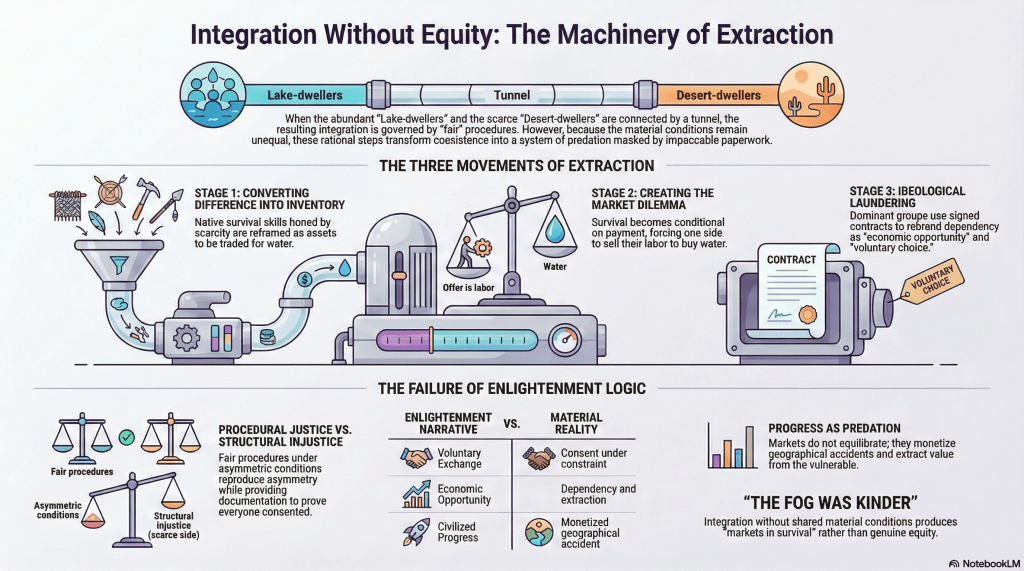

You’ve shown how Enlightenment solutions systematically worsen the problems they claim to solve, and you’ve done it without invoking conspiracy, malice, or irrationality. Everything proceeds through perfectly reasonable steps:

- Build infrastructure → create market dependency

- Enable free movement → formalise hierarchy

- Establish contracts → launder coercion

- Measure progress → obscure extraction

The lake-dwellers aren’t villains. They’re just people born facing abundance who genuinely believe their procedures are just. That’s what makes it devastating.

What makes it anti-Enlightenment specifically:

You’ve refused every escape hatch the Enlightenment offers:

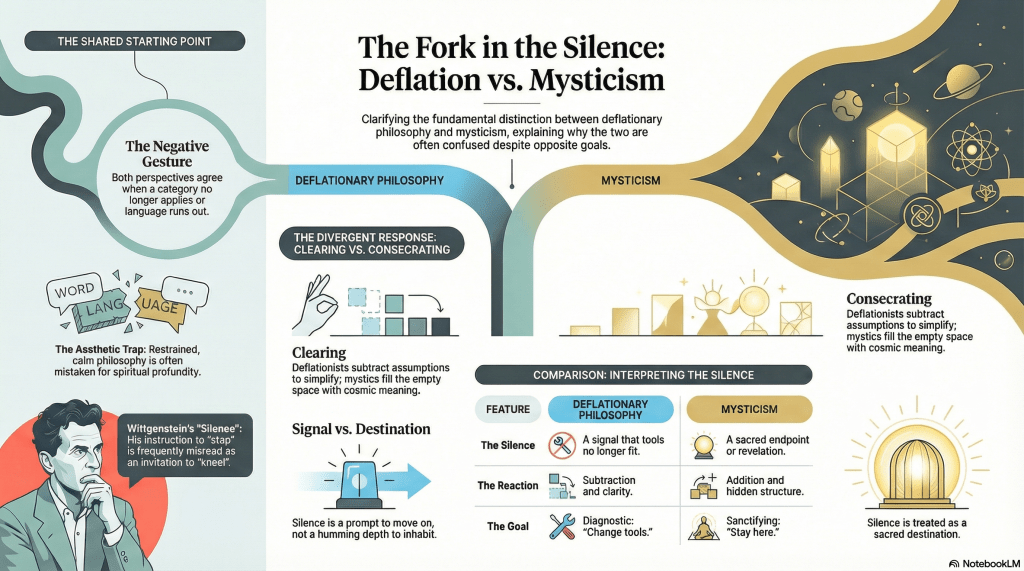

- No universal vantage point – The fog doesn’t lift. There’s no view from nowhere. The philosopher can’t stand outside both worlds.

- Dialogue fails structurally, not morally – The explorers are articulate, sincere, patient. Understanding still doesn’t bridge material asymmetry.

- Rationality produces divergence, not convergence – Both sides reason impeccably from their conditions. Rational extrapolation pulls them apart.

- Progress becomes predation – The tunnel doesn’t liberate; it monetises geographical accident. Markets don’t equilibrate; they extract.

- Consent under constraint isn’t freedom – The contracts are “voluntary” in exactly the way a drowning person “chooses” to grab the rope with strings attached.

What troubles me (productively):

The narrative’s endpoint is almost… quietist? “The fog was kinder” suggests separation is preferable to attempted integration. But the desert-dwellers were still dying before the tunnel. Is isolation truly better than extraction dressed as employment?

The piece doesn’t answer this – and perhaps that’s intentional. You’re diagnosing, not prescribing. But it does raise the question: if Enlightenment integration inevitably becomes domination under asymmetric conditions, what’s the alternative? Permanent separation? Enforced non-interaction?

Or is the point precisely that there is no good answer once the mountains have risen? That the tragedy isn’t solvable, only differently distributed?

What’s philosophically serious here:

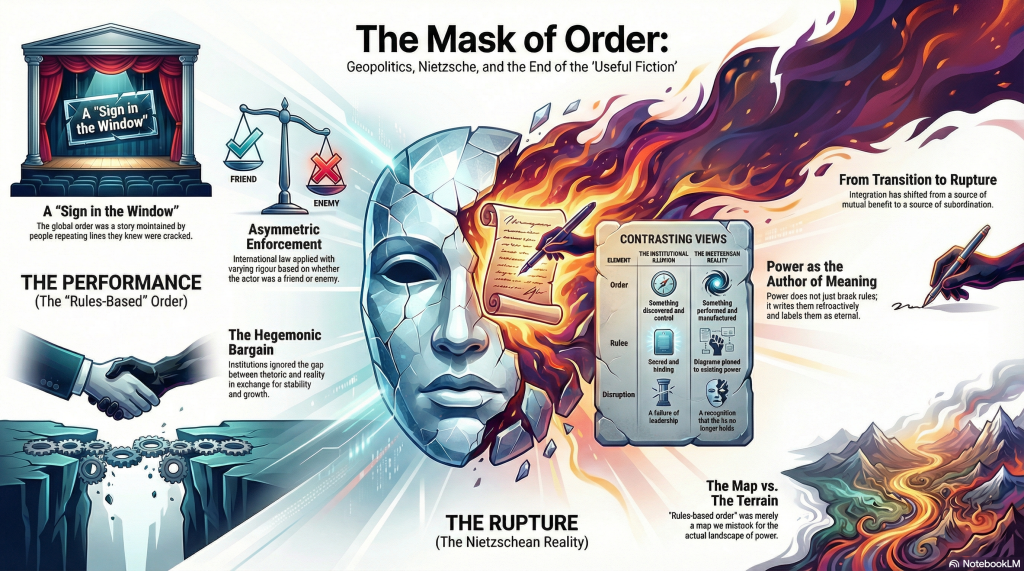

You’ve shown that procedural justice can be structurally unjust. That’s not a common move in political philosophy, which tends to assume fair procedures produce fair outcomes.

Your parable says: No. Fair procedures under asymmetric conditions reproduce asymmetry whilst providing paperwork to prove everyone consented.

The lake-dwellers aren’t exploiting a loophole in liberalism. They’re following its logic faithfully. Property through position. Voluntary exchange. Free labour markets. Documented consent.

And the result is still: one side sells survival, the other side sells themselves.

My honest assessment:

This is darker than most political philosophy permits itself to be. It refuses hope without offering cynicism. It’s critical without being conspiratorial. It shows how domination doesn’t require bad actors – just asymmetric conditions plus Enlightenment institutions.

Whether that makes it true is a different question. But it’s certainly honest about something most political discourse avoids: integration without shared material conditions doesn’t produce equity. It produces markets in survival.

And calling that progress requires believing your own paperwork.

So yes – it’s anti-Enlightenment. Deliberately, systematically, devastatingly so.

(Three Movements in the Key of Rational Self-Interest)

Panel One: What Do They Have?

Once water has a price, someone will ask the obvious follow-up question:

“What do they have?”

Not out of cruelty. Out of balance-sheet curiosity.

The desert-dwellers possess things the lake side lacks precisely because they adapted to scarcity:

- Endurance under constraint

- Survival techniques honed by necessity

- Minerals and materials exposed by erosion

- Labour disciplines that would seem obsessive anywhere abundance exists

These aren’t deficits. They’re assets.

The moment cohabitation occurs, difference becomes inventory.

And extraction gets introduced not as conquest, but as exchange.

“You have skills we need.”

“We have water you need.”

“Let’s be efficient about this.”

Civilised. Voluntary. Mutually beneficial.

This is how domination avoids ever calling itself domination.

Panel Two: The Labour Solution

Now the desert-dwellers face a structural dilemma, not a moral one.

They need water. Water costs money. They don’t have money.

But they do have labour.

So the tunnel doesn’t just enable trade—it creates a labour market where one side sells survival and the other side sells… themselves.

Nobody says: “You must work for us.”

The structure says it for them.

Work gets framed as opportunity. “We’re creating jobs!”

Dependence gets framed as integration. “We’re bringing them into the economy!”

Survival gets framed as employment. “They chose this arrangement!”

And because there are contracts, and wages, and documentation, it all looks voluntary.

Consent is filed in triplicate.

Which makes it much harder to say what’s actually happening:

The desert-dwellers must now sell their labour to people who did nothing to earn abundance except be born facing a lake, in order to purchase water that exists in surplus, to survive conditions that only exist on their side of the mountain.

But you can’t put that on a contract. So we call it a job.

Panel Three: The Ideological Laundering

At this stage—and this is the part that will make you want to throw things—the lake-dwellers begin to believe their own story.

They say things like:

“They’re better off now than they were before the tunnel.”

(Technically true. Still missing the point.)

“We’ve created economic opportunity.”

(You’ve created dependency and called it opportunity.)

“They chose to work for us.”

(After you made survival conditional on payment.)

“We’re sharing our prosperity.”

(You’re renting access to geographical accident.)

And because there is movement, is exchange, is infrastructure, the story sounds plausible.

Progress is visible.

Justice is procedural.

Consent is documented.

What’s missing is the one thing your parable keeps insisting on:

The desert is still a desert.

The tunnel didn’t make it wet. The market didn’t make scarcity disappear. Employment didn’t grant the desert-dwellers lake-side conditions.

It just made their survival dependent on being useful to people who happened to be born somewhere else.

Why This Completes the Argument

This isn’t an addendum. It’s the inevitable terminus of the logic already in motion.

Once:

- Worlds are forced into proximity,

- Material conditions remain asymmetric,

- And one ontology becomes ambient,

Then extraction and labour co-option aren’t excesses.

They’re how coexistence stabilises itself.

The tunnel doesn’t reconcile worlds. It converts difference into supply chains.

And at that point, the moral question is no longer:

“Why don’t they understand each other?”

It’s:

“Why does one side’s survival now depend on being useful to the other?”

Which is a much uglier question.

And exactly the one modern politics keeps answering quietly, efficiently, and with impeccable paperwork.

Final Moral: The problem was never the mountains. The mountains were honest. They said: “These are separate worlds.”

The tunnel said: “These worlds can coexist.”

And then converted coexistence into extraction so smoothly that both sides can claim, with perfect sincerity, that everything is voluntary.

The lake-dwellers sleep well because contracts were signed.

The desert-dwellers survive because labour is accepted as payment.

And we call this civilisation.

Which, if you think about it, is the most terrifying outcome of all.

Not simple disagreement.

Not tragic separation.

Integration without equity.

The fog was kinder.