This is a continuation of a prior narrative.

But wait—surely someone will object—what if we just built a tunnel?

Remove the barrier! Enable free movement! Let people see both sides! Markets will equilibrate! Efficiency will reign! Progress!

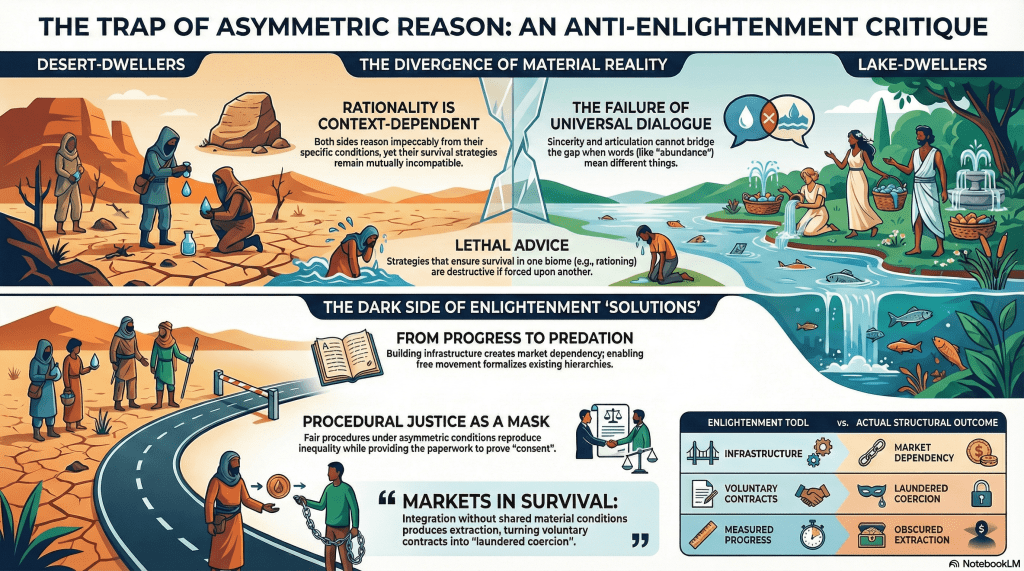

So fine. The desert-dwellers say, “Let’s build a tunnel”.

Engineers arrive. Explosives are deployed. A passage is carved through the mountain. The fog clears inside the tunnel itself. You can now walk from lake to desert, desert to lake, without risking death by altitude.

Congratulations. Now what?

The lake doesn’t flow through the tunnel. The desert doesn’t migrate. The material conditions remain exactly as they were, except now they’re adjacent rather than separated.

And here’s where Modernity performs its favourite trick: it converts geographical accident into property rights.

The lake-dwellers look at their neighbours walking from the tunnel and think: “Ah. We have water. They need water. We should probably charge for that.”

Not out of malice. Out of perfectly rational economic calculation. After all, we maintain these shores (do we, though?). We cultivate these reeds (they grow on their own). We steward this resource (it replenishes whether we steward it or not).

John Locke would be beaming. Property through labour! Mixing effort with natural resources! The foundation of legitimate ownership!

Except nobody laboured to make the lake.

It was just there. On one side. Not the other.

The only “labour” involved was being born facing the right direction.

Primacy of position masquerading as primacy of effort.

What Actually Happens

The desert-dwellers can now visit. They can walk through the tunnel, emerge on the shore, and confirm with their own eyes: yes, there really is abundance here. Yes, the water is drinkable. Yes, there is genuinely enough.

And they can’t touch a drop without payment.

The tunnel hasn’t created shared resources. It’s created a market in geographical accident.

The desert-dwellers don’t become lake-dwellers. They become customers.

The lake-dwellers don’t become more generous. They become vendors.

And the separation—formerly enforced by mountains and fog and the physical impossibility of crossing—is now enforced by price.

Which is, if anything, more brutal. Because now the desert-dwellers can see what they cannot have. They can stand at the shore, watch the water lap at the sand, understand perfectly well that scarcity is not a universal condition but a local one—

And still return home thirsty unless they can pay.

The Lockean Slight-of-Hand

Here’s what Locke tried to tell us: property is legitimate when you mix your labour with natural resources.

Here’s what he failed to mention: if you happen to be standing where the resources already are, you can claim ownership without mixing much labour at all.

The lake people didn’t create abundance. They just didn’t leave.

But once the tunnel exists, that positional advantage converts into property rights, and property rights convert into markets, and markets convert into the permanent enforcement of inequality that geography used to provide temporarily.

Before the tunnel: “We cannot share because of the mountains.”

After the tunnel: “We will not share because of ownership.”

Same outcome. Different justification. Significantly less honest.

The Desert-Dwellers’ Dilemma

Now the desert people face a choice.

They can purchase water. Which means accepting that their survival depends on the economic goodwill of people who did nothing to earn abundance except be born near it.

Or they can refuse. Maintain their careful, disciplined, rationed existence. Remain adapted to scarcity even though abundance is now—tantalisingly, insultingly—visible through a tunnel.

Either way, the tunnel hasn’t solved the moral problem.

It’s just made the power differential explicit rather than geographical.

And if you think that’s an improvement, ask yourself: which is crueller?

Being separated by mountains you cannot cross, or being separated by prices you cannot pay, whilst standing at the shore watching others drink freely?

TheBit Where This Connects to Actual Politics

So when Modernity tells you that the solution to structural inequality is infrastructure, markets, and free movement—

Ask this:

Does building a tunnel make the desert wet?

Does creating a market make abundance appear where it didn’t exist?

Does free movement help if you still can’t afford what’s on the other side?

The tunnel is a technical solution to a material problem.

But the material problem persists.

And what the tunnel actually creates is a moral problem: the formalisation of advantage that was previously just an environmental accident.

The lake-dwellers now have something to sell.

The desert-dwellers now have something to buy.

And we call this progress.

Moral: If your political metaphor doesn’t account for actual rivers, actual deserts, and actual fog, it’s not a metaphor. It’s a fairy tale. And unlike fairy tales, this one doesn’t end with a reunion.

It ends with two people walking home, each convinced the other is perfectly reasonable and completely unsurvivable.

Unless, of course, we build a tunnel.

In which case, it ends with one person selling water to the other, both convinced this is somehow more civilised than being separated by mountains.

Which, if you think about it, is far more terrifying than simple disagreement.