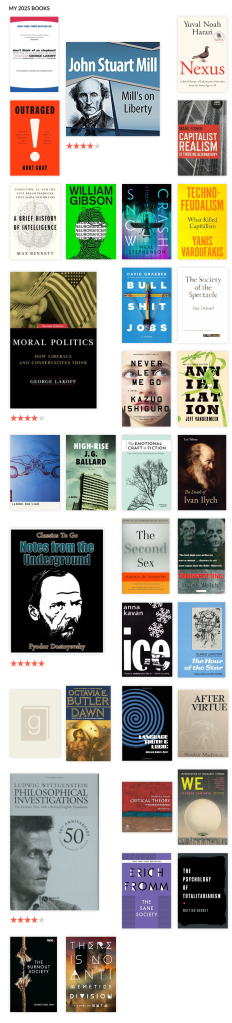

2025 has been a good year for this blog. I’ve crossed the 1,000-post mark, and this year it has had over 30,000 page views – best year ever. This month was the best month ever, and 1st December was the most popular day ever. That’s a lot of ‘evers’.

I shared the remainder of this post on my Ridley Park fiction blog – same reader, same books, same opinion. Any new content added below is in red.

I genuinely loathe top X lists, so let us indulge in some self-loathing. I finished these books in 2026. As you can see, they cross genres, consist of fiction and non-fiction, and don’t even share temporal space. I admit that I’m a diverse reader and, ostensibly, writer. Instead of just the top 5. I’ll shoot for the top and bottom 5 to capture my anti-recommendations. Within categories are alphabetical.

Fiction

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro – A slow reveal about identity, but worth the wait.

This was very philosophical and psychological. Nothing appeared to happen until chapter 7, as I recall. I felt like I was just eavesdropping on some school chums, which I was. Then came the big reveal.

Notes from Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky – Classic unreliable narrator.

Again, philosophical, psychological. I liked it.

There Is No Antimemetics Division by QNTM (AKA Sam Hughes) – Points for daring to be different and hitting the landing.

This, I read because I was attracted to the premise of memory as it might affect language. It touched on this a tad, but it was mostly about memory, anti-memory, and constructed selves. How can one experience a contiguous, diachronic self with memory gaps? It never quite got that deep, that on occasion it did, as far as I recall.

Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh – Scottish drugs culture and bonding mates narrative.

This is an age-old cult classic – much better than the already excellent films. Fills in what the film cut for its medium. I read several other Welsh books. Filth was an honourable mention, which I also made connexions to Antimemetics, above.

We by Yevgeny Zamyatin – In the league of 1984 and Brave New World, but without the acclaim.

This flagged a tad at the end, but it was prescient and released in 1922, decades before 1984 and Brave New World. Worth the read.

Nonfiction

Capitalist Realism by Mark Fisher – Explains why most problems are social, not personal or psychological. Follows Erich Fromm’s Sane Society, which I also read in 2025 and liked, but it fell into the ‘lost the trail’ territory at some point, so it fell off the list.

Moral Politics by George Lakoff

Evidently, I forgot to explain myself in my prior post. I refer to this book and its trade counterpart, Don’t Think of an Elephant, which is more of a political polemic, but still worth the read. It’s also shorter. This is about Moral politics – duh! – but it’s about moral language. It was a precursor to Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion or Kurt Gray’s Outraged! I found Haidt’s work interesting but reductive; I found Gray’s work merely reductive.

This said, Lakoff and Haidt were the vector through which I came upon my language ontology theory that further confounds language insufficiency. To be sure, Haidt was an unnecessary point, but it did emphasise it. Haidt’s frameworks also give me something to riff on.

Technofeudalism by Yanis Varoufakis – Explains why Capitalism is already dead on arrival.

Nothing much to add here. Technofeudalism is economic fare, albeit with philosophical implications. I enjoyed it. Yanis is also an interesting speaker.

NB: Some of the other books had great pieces of content, but failed as books. They may have been better as essays or blog posts. They didn’t have enough material for a full book. The Second Sex had enough for a book, but then Beauvoir poured in enough for two books. She should have quit whilst she was ahead.

Full disclosure: I don’t always record my reading on Goodreads, but I try.

Bottom of the Barrel

Crash by J.G. Ballard – Hard no. I also didn’t like High-rise, but it was marginally better, and I didn’t want to count an author twice.

Nah. I felt he was trying to hard for shock value. It didn’t shock, but it put me off. At least High-rise represented an absurd cultural microcosm. I just wanted the story to be over. Luckily, I read both of these sequentially whilst on holiday, so I wasn’t looking to ingest anything serious.

Neuromancer by William Gibson – I don’t tend to like SciFi. This is a classic. Maybe it read differently back in the day. Didn’t age well.

Nexus by Yuval Harari – Drivel. My mates goaded me into reading this. I liked Sapiens. He’s gone downhill since then. He’s a historian, not a futurist.

Outraged! by Kurt Gray – Very reductionist view of moral harm, following the footsteps of George Lakoff and Jonathan Haidt.

See comments above. ☝️

Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord – A cautionary tale on why writing a book on LSD may not be a recipe for success.

Honourable Mention

Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer was also good, but my cutoff was at 5. Sorry, Jeff.

I did like this, and it was much better than the Natalie Portman film adaptation. This is the first book in a trilogy. I absolutely hated the second instalment. The third was not as good as the first, but it tried to get back on track from the derailment of the second. As I wrote in public reviews, the second book could have been a prologue chapter to the third book with all of the relevant information I cared about. You could skip the second story with almost no material effect on the story or character arcs.