The Broken Map

You wake up in the middle of a collapsing building. Someone hands you a map and says, find your way home. You look down. The map is for a different building entirely. One that was never built. Or worse, one that was demolished decades ago. The exits don’t exist. The staircases lead nowhere.

This is consciousness.

We didn’t ask for it. We didn’t choose it. And the tools we inherited to navigate it—language, philosophy, our most cherished questions—were drawn for a world that does not exist.

Looking back at my recent work, I realise I’m assembling a corpus of pessimism. Not the adolescent kind. Not nihilism as mood board. Something colder and more practical: a willingness to describe the structures we actually inhabit rather than the ones we wish were there.

It starts with admitting that language is a compromised instrument. A tool evolved for coordination and survival, not for metaphysical clarity. And nowhere is this compromise more concealed than in our most sanctified word of inquiry.

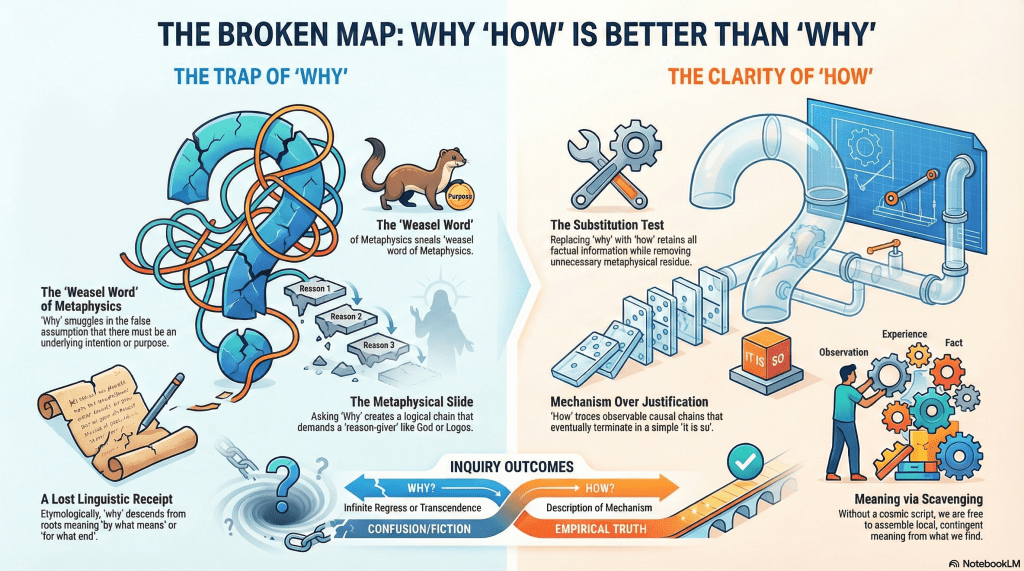

1. The Weasel Word

We treat “why” as the pinnacle of human inquiry. The question that separates us from animals. Philosophy seminars orbit it. Religions are scaffolded around it. Children deploy it until adults retreat in defeat.

But “why” is a weasel word. A special case of how wearing an unnecessary coat of metaphysics.

The disguise is thinner in other languages. French pourquoi, Spanish por qué, Italian perché all literally mean for what. Japanese dōshite means by what way. Mandarin wèishénme is again for what. The instrumental skeleton is right there on the surface. Speakers encounter it every time they ask the question.

In the Indo-European lineage, “why” descends from the same root as “what”. It began as an interrogative of means and manner, not cosmic purpose. To ask “why” was originally to ask by what mechanism or for what end. Straightforward, workmanlike questions.

Over time, English inflated this grammatical shortcut into something grander. A demand for ultimate justification. For the Reason behind reasons.

The drift was slow enough that it went unnoticed. The word now sounds like a deeper category of inquiry. As if it were pointing beyond mechanism toward metaphysical bedrock.

The profundity is a trick of phonetic history. And a surprising amount of Anglo-American metaphysics may be downstream of a language that buried the receipt.

2. What “Why” Smuggles In

To see the problem clearly, follow the logic that “why” quietly encourages.

When we ask “Why is there suffering?” we often believe we are asking for causes. But the grammar primes us for something else entirely. It whispers that there must be a justification. A reason-giver. An intention behind the arrangement of things.

The slide looks like this:

“Why X?”

→ invites justification rather than description

→ suggests intention or purpose

→ presumes a mind capable of intending

→ requires reasons for those intentions

→ demands grounding for those reasons

At that point the inquiry has only two exits: infinite regress or a metaphysical backstop. God. Logos. The Good. A brute foundation exempt from the very logic that summoned it.

This is not a failure to answer the question. It is the question functioning exactly as designed.

Now contrast this with how.

“How did X come about?”

→ asks for mechanism

→ traces observable causal chains

→ bottoms out in description

“How” eventually terminates in it is so. “Why”, as commonly used, never does. It either spirals forever or leaps into transcendence.

This is not because we lack information. It is because the grammatical form demands more than the world can supply.

3. The Substitution Test

Here is the simplest diagnostic.

Any genuine informational “why” question can be reformulated as a “how” question without losing explanatory power. What disappears is not content but metaphysical residue.

“Why were you late?”

→ “How is it that you are late?”

“My car broke down” answers both.

“Why do stars die?”

→ “How do stars die?”

Fuel exhaustion. Gravitational collapse. Mechanism suffices.

“Why did the dinosaurs go extinct?”

→ “How did the dinosaurs go extinct?”

Asteroid impact. Climate disruption. No intention required.

Even the grand prize:

“Why is there something rather than nothing?”

→ “How is it that there is something?”

At which point the question either becomes empirical or dissolves entirely into it is. No preamble.

Notice the residual discomfort when “my car broke down” answers “why were you late”. Something feels unpaid. The grammar had primed the listener for justification, not description. For reasons, not causes.

The car has no intentions. It broke. That is the whole truth. “How” accepts this cleanly. “Why” accepts it while still gesturing toward something that was never there.

4. The Black Box of Intention

At this point the problem tightens.

If “why” quietly demands intentions, and intentions are not directly accessible even to the agents who supposedly have them, then the entire practice is built on narrative repair.

We do not observe our intentions. We infer them after the fact. The conscious mind receives a press release about decisions already made elsewhere and calls it a reason. Neuroscience has been showing this for decades.

So:

- Asking others why they acted requests a plausible story about opaque processes

- Asking oneself why one acted requests confabulation mistaken for introspection

- Asking the universe why anything exists requests a fiction about a mind that is not there

“How” avoids this entirely. It asks for sequences, mechanisms, conditions. It does not require anyone to perform the ritual of intention-attribution. It does not demand that accidents confess to purposes.

5. Thrownness Without a Vantage Point

I stop short of calling existence a mistake. A mistake implies a standard that was failed. A plan that went wrong. I prefer something colder: the accident.

Human beings find themselves already underway, without having chosen the entry point or the terms. Heidegger called this thrownness. But the structure is not uniquely human.

The universe itself admits no vantage point from which it could justify itself. There is no external tribunal. No staging ground. No meta-position from which existence could be chosen or refused.

This is not a claim about cosmic experience. It is a structural observation about the absence of justification-space. The question “Why is there something rather than nothing?” presumes a standpoint that does not exist. It is a grammatical hallucination.

Thrownness goes all the way down. Consciousness is thrown into a universe that is itself without preamble. We are not pockets of purposelessness in an otherwise purposeful cosmos. We are continuous with it.

The accident runs through everything.

6. Suchness

This is not a new insight. Zen Buddhism reached it by a different route.

Where Western metaphysics treats “why” as an unanswered question, Zen treats it as malformed. The koan does not await a solution. It dissolves the demand for one. When asked whether a dog has Buddha-nature, the answer Mu does not negate or affirm. It refuses the frame.

Tathātā—suchness—names reality prior to justification. Things as they are, before the demand that they make sense to us.

This is not mysticism. It is grammatical hygiene.

Nietzsche smashed idols with a hammer. Zen removes the altar entirely. Different techniques, same target: the metaphysical loading we mistake for depth.

7. Scavenging for Meaning

If there is no True Why, no ultimate justification waiting beneath the floorboards of existence, what remains?

For some, this sounds like collapse. For me, it is relief.

Without a cosmic script, meaning becomes something we assemble rather than discover. Local. Contingent. Provisional. Real precisely because it is not guaranteed.

I find enough purpose in the warmth of a partner’s hand, in the internal logic of a sonata, in the seasonal labour of maintaining a garden. These things organise my days. They matter intensely. And they do so without claiming eternity.

I hold them lightly because I know the building is slated for demolition. Personally. Biologically. Cosmologically. That knowledge does not drain them of colour. It sharpens them.

This is what scavenging means. You build with what you find. You use what works. You do not pretend the materials were placed there for you.

Conclusion: The Sober Nihilist

To be a nihilist in this sense is not to despair. It is to stop lying about the grammar of the universe.

“Why” feels like a meaningful inquiry, but it does not connect to anything real in the way we imagine. It demands intention from a cosmos that has none and justification from accidents that cannot supply it.

“How” is enough. It traces causes. It observes mechanisms. It accepts that things sometimes bottom out in is.

Once you stop asking the universe to justify itself, you are free to deal with what is actually here. The thrown, contingent, occasionally beautiful business of being alive.

I am a nihilist not because I am lost, but because I have put down a broken map. I am looking at what is actually in front of me.

And that, it turns out, is enough.

Full Disclosure: This article was output by ChatGPT after an extended conversation with it, Claude, and me. Rather than trying to recast it in my voice, I share it as is. I had started this as a separate post on nihilism, and we ended up here. Claude came up with the broken map story at the start and Suchness near the end. I contributed the weasel words, the ‘how’ angle, the substitution test, the metaphysics of motivation and intention, thrownness (Geworfenheit), Zen, and nihilism. ChatGPT merely rendered this final output after polishing my conversation with Claude.

We had been discussing Cioran, Zapffe, Benatar, and Ligotti, but they got left on the cutting room floor along the way.