The Space Between

In the great philosophical tug-of-war between materialism and idealism, where reality is argued to be either wholly independent of perception or entirely a construct of the mind, there lies an underexplored middle ground—a conceptual liminal space that we might call “Intersectionalism.” This framework posits that reality is neither purely objective nor subjective but emerges at the intersection of the two. It is the terrain shaped by the interplay between what exists and how it is perceived, mediated by the limits of human cognition and sensory faculties.

Intersectionalism offers a compelling alternative to the extremes of materialism and idealism. By acknowledging the constraints of perception and interpretation, it embraces the provisionality of knowledge, the inevitability of blind spots, and the productive potential of uncertainty. This essay explores the foundations of Intersectionalism, its implications for knowledge and understanding, and the ethical and practical insights it provides.

Reality as an Intersection

At its core, Intersectionalism asserts that reality exists in the overlapping space between the objective and the subjective. The objective refers to the world as it exists independently of any observer—the “terrain.” The subjective encompasses perception, cognition, and interpretation—the “map.” Reality, then, is not fully contained within either but is co-constituted by their interaction.

Consider the act of seeing a tree. The tree, as an object, exists independently of the observer. Yet, the experience of the tree is entirely mediated by the observer’s sensory and cognitive faculties. Light reflects off the tree, enters the eye, and is translated into electrical signals processed by the brain. This process creates a perception of the tree, but the perception is not the tree itself.

This gap between perception and object highlights the imperfect alignment of subject and object. No observer perceives reality “as it is” but only as it appears through the interpretive lens of their faculties. Reality, then, is a shared but imperfectly understood phenomenon, subject to distortion and variation across individuals and species.

The Limits of Perception and Cognition

Humans, like all organisms, perceive the world through the constraints of their sensory and cognitive systems. These limitations shape not only what we can perceive but also what we can imagine. For example:

- Sensory Blind Spots: Humans are limited to the visible spectrum of light (~380–750 nm), unable to see ultraviolet or infrared radiation without technological augmentation. Other animals, such as bees or snakes, perceive these spectra as part of their natural sensory worlds. Similarly, humans lack the electroreception of sharks or the magnetoreception of birds.

- Dimensional Constraints: Our spatial intuition is bounded by three spatial dimensions plus time, making it nearly impossible to conceptualise higher-dimensional spaces without resorting to crude analogies (e.g., imagining a tesseract as a 3D shadow of a 4D object).

- Cognitive Frameworks: Our brains interpret sensory input through patterns and predictive models. These frameworks are adaptive but often introduce distortions, such as cognitive biases or anthropocentric assumptions.

This constellation of limitations suggests that what we perceive and conceive as reality is only a fragment of a larger, potentially unknowable whole. Even when we extend our senses with instruments, such as infrared cameras or particle detectors, the data must still be interpreted through the lens of human cognition, introducing new layers of abstraction and potential distortion.

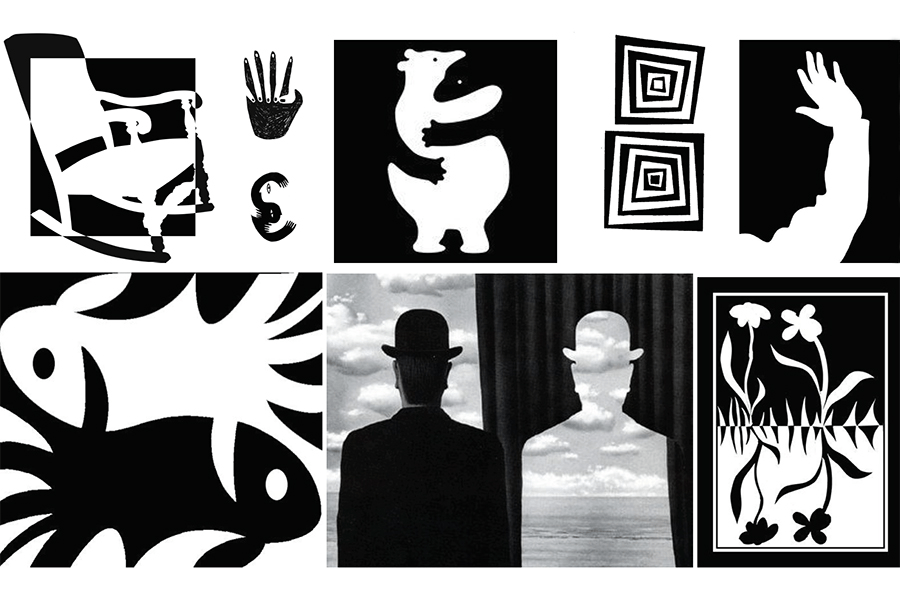

The Role of Negative Space

One of the most intriguing aspects of Intersectionalism is its embrace of “negative space” in knowledge—the gaps and absences that shape what we can perceive and understand. A compelling metaphor for this is the concept of dark matter in physics. Dark matter is inferred not through direct observation but through its gravitational effects on visible matter. It exists as a kind of epistemic placeholder, highlighting the limits of our current sensory and conceptual tools.

Similarly, there may be aspects of reality that elude detection altogether because they do not interact with our sensory or instrumental frameworks. These “unknown unknowns” serve as reminders of the provisional nature of our maps and the hubris of assuming completeness. Just as dark matter challenges our understanding of the cosmos, the gaps in our perception challenge our understanding of reality itself.

Practical and Ethical Implications

Intersectionalism’s recognition of perceptual and cognitive limits has profound implications for science, ethics, and philosophy.

Science and Knowledge

In science, Intersectionalism demands humility. Theories and models, however elegant, are maps rather than terrains. They approximate reality within specific domains but are always subject to revision or replacement. String theory, for instance, with its intricate mathematics and reliance on extra dimensions, risks confusing the elegance of the map for the completeness of the terrain. By embracing the provisionality of knowledge, Intersectionalism encourages openness to new paradigms and methods that might better navigate the negative spaces of understanding.

Ethics and Empathy

Ethically, Intersectionalism fosters a sense of humility and openness toward other perspectives. If reality is always interpreted subjectively, then every perspective—human, animal, or artificial—offers a unique and potentially valuable insight into the intersection of subject and object. Recognising this pluralism can promote empathy and cooperation across cultures, species, and disciplines.

Technology and Augmentation

Technological tools extend our sensory reach, revealing previously unseen aspects of reality. However, they also introduce new abstractions and biases. Intersectionalism advocates for cautious optimism: technology can help illuminate the terrain but will never eliminate the gap between map and terrain. Instead, it shifts the boundaries of our blind spots, often revealing new ones in the process.

Conclusion: Navigating the Space Between

Intersectionalism provides a framework for understanding reality as a shared but imperfect intersection of subject and object. It rejects the extremes of materialism and idealism, offering instead a middle path that embraces the limitations of perception and cognition while remaining open to the possibilities of negative space and unknown dimensions. In doing so, it fosters humility, curiosity, and a commitment to provisionality—qualities essential for navigating the ever-expanding terrain of understanding.

By acknowledging the limits of our maps and the complexity of the terrain, Intersectionalism invites us to approach reality not as a fixed and knowable entity but as an unfolding interplay of perception and existence. It is a philosophy not of certainty but of exploration, always probing the space between.