Cheap Adversaries, Outsourced Ego, and Engineered Critique ← ChatGPT is obsessed with subtitles.

There is a peculiar anxiety around admitting that one uses generative AI in serious intellectual work. The anxiety usually takes one of two forms. Either the AI is accused of replacing thinking, or it is accused of flattering the thinker into delusion. Both charges miss the point, and both underestimate how brittle early-stage human peer review often is.

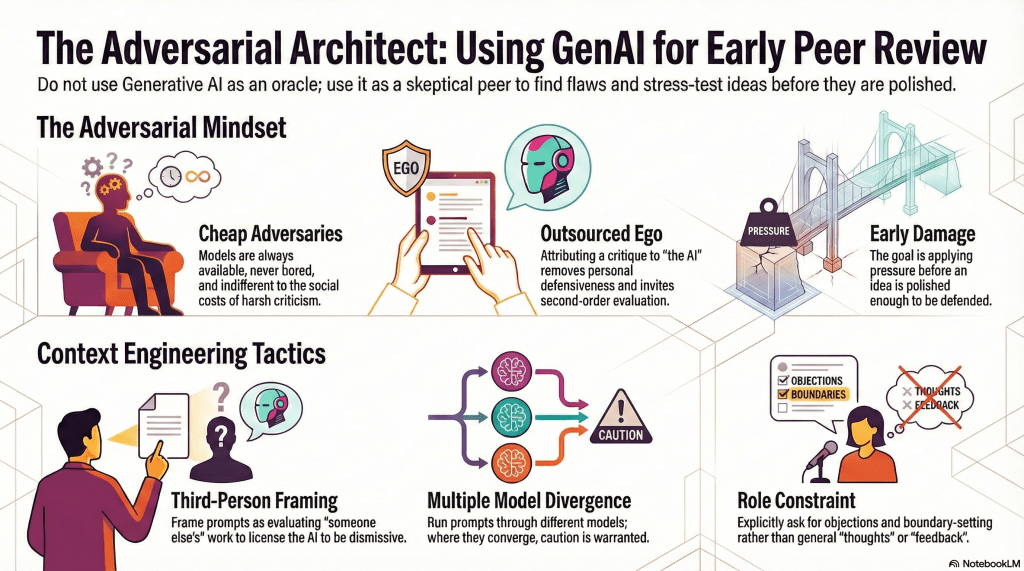

What follows is not a defence of AI as an oracle, nor a claim that it produces insight on its own. It is an account of how generative models can be used – deliberately, adversarially, and with constraints – as a form of early peer pressure. Not peer review in the formal sense, but a rehearsal space where ideas are misread, overstated, deflated, and occasionally rescued from themselves.

The unromantic workflow

The method itself is intentionally dull:

- Draft a thesis statement.

Rinse & repeat. - Draft an abstract.

Rinse & repeat. - Construct an annotated outline.

Rinse & repeat. - Only then begin drafting prose.

At each stage, the goal is not encouragement or expansion but pressure. The questions I ask are things like:

- Is this already well-trodden ground?

- Is this just X with different vocabulary?

- What objection would kill this quickly?

- What would a sceptical reviewer object to first?

The key is timing. This pressure is applied before the idea is polished enough to be defended. The aim is not confidence-building; it is early damage.

Why generative AI helps

In an ideal world, one would have immediate access to sharp colleagues willing to interrogate half-formed ideas. In practice, that ecology is rarely available on demand. Even when it is, early feedback from humans often comes bundled with politeness, status dynamics, disciplinary loyalty, or simple fatigue.

Generative models are always available, never bored, and indifferent to social cost. That doesn’t make them right. It makes them cheap adversaries. And at this stage, adversaries are more useful than allies.

Flattery is a bias, not a sin

Large language models are biased toward cooperation. Left unchecked, they will praise mediocre ideas and expand bad ones into impressive nonsense. This is not a moral failure. It is a structural bias.

The response is not to complain about flattery, but to engineer against it.

Sidebar: A concrete failure mode

I recently tested a thesis on Mistral about object permanence. After three exchanges, the model had escalated a narrow claim into an overarching framework, complete with invented subcategories and false precision. The prose was confident. The structure was impressive. The argument was unrecognisable.

This is the Dunning-Kruger risk in practice. The model produced something internally coherent that I lacked the domain expertise to properly evaluate. Coherence felt like correctness.

The countermeasure was using a second model, which immediately flagged the overreach. Disagreement between models is often more informative than agreement.

Three tactics matter here.

1. Role constraint

Models respond strongly to role specification. Asking explicitly for critique, objections, boundary-setting, and likely reviewer resistance produces materially different output than asking for ‘thoughts’ or ‘feedback’.

2. Third-person framing

First-person presentation cues collaboration. Third-person presentation cues evaluation.

Compare:

- ‘Here’s my thesis; what do you think?‘

- ‘Here is a draft thesis someone is considering. Please evaluate its strengths, weaknesses, and likely objections.‘

The difference is stark. The first invites repair and encouragement. The second licenses dismissal. This is not trickery; it is context engineering.

3. Multiple models, in parallel

Different models have different failure modes. One flatters. Another nitpicks. A third accuses the work of reinventing the wheel. Their disagreement is the point. Where they converge, caution is warranted. Where they diverge, something interesting is happening.

‘Claude says…’: outsourcing the ego

One tactic emerged almost accidentally and turned out to be the most useful of all.

Rather than responding directly to feedback, I often relay it as:

“Claude says this…”

The conversation then shifts from defending an idea to assessing a reading of it. This does two things at once:

- It removes personal defensiveness. No one feels obliged to be kind to Claude.

- It invites second-order critique. People are often better at evaluating a critique than generating one from scratch.

This mirrors how academic peer review actually functions:

- Reviewer 2 thinks you’re doing X.

- That seems like a misreading.

- This objection bites; that one doesn’t.

The difference is temporal. I am doing this before the draft hardens and before identity becomes entangled with the argument.

Guardrails against self-delusion

There is a genuine Dunning–Kruger risk when working outside one’s formal domain. Generative AI does not remove that risk. Used poorly, it can amplify it.

The countermeasure is not humility as a posture, but friction as a method:

- multiple models,

- adversarial prompting,

- third-person evaluation,

- critique of critiques,

- and iterative narrowing before committing to form.

None of this guarantees correctness. It does something more modest and more important: it makes it harder to confuse internal coherence with external adequacy.

What this cannot do

It’s worth being explicit about the limits. Generative models cannot tell you whether a claim is true. They can tell you how it is likely to be read, misread, resisted, or dismissed. They cannot arbitrate significance. They cannot decide what risks are worth taking. They cannot replace judgment. Those decisions remain stubbornly human.

What AI can do – when used carefully – is surface pressure early, cheaply, and without social cost. It lets ideas announce their limits faster, while those limits are still negotiable.

A brief meta-note

For what it’s worth, Claude itself was asked to critique an earlier draft of this post. It suggested compressing the familiar arguments, foregrounding the ‘Claude says…’ tactic as the real contribution, and strengthening the ending by naming what the method cannot do.

That feedback improved the piece. Which is, rather conveniently, the point.