The struggle is real. There is an odd occupational hazard that comes with writing deflationary philosophy: mystics keep turning up to thank you for your service.

This is always mildly bewildering. One spends a great deal of time dismantling metaphysical furniture, only to discover a small group lighting incense in the newly cleared space. Candles appear. Silence thickens. Someone whispers ineffable. Nope. The filing cabinet was just mislabeled.

The problem is not misunderstanding. It’s reuse.

It is tempting to think this is a simple misreading: I say this concept breaks down here, and someone hears you have glimpsed the ultimate. But that’s too kind. What’s really happening is more interesting. Mysticism does not merely misunderstand deflationary work; it feeds on the same linguistic moves and then stops too early.

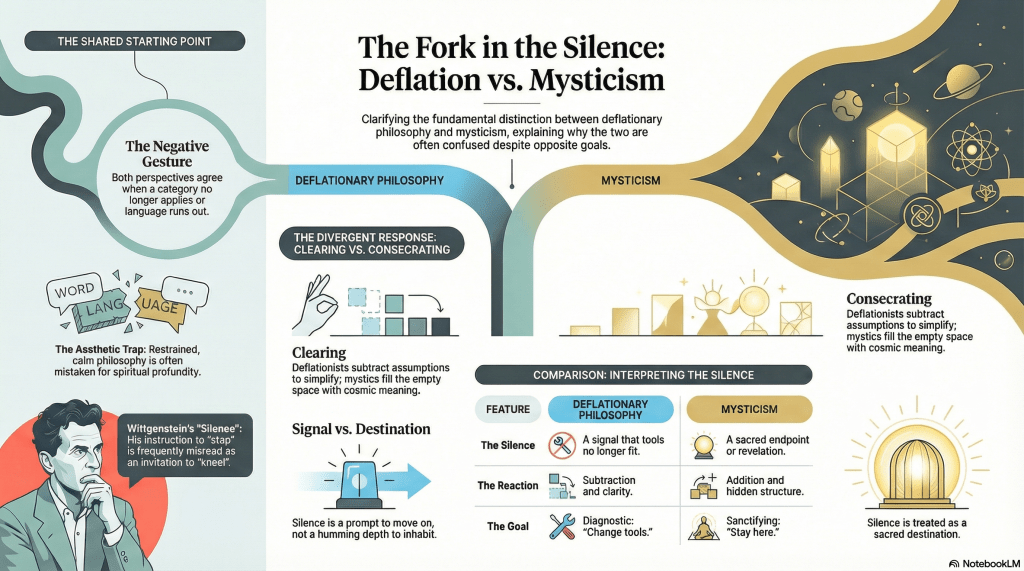

Both mysticism and deflation rely on negative gestures:

- “This description fails.”

- “That category no longer applies.”

- “Our usual language runs out.”

Up to this point, they are indistinguishable. The fork comes immediately after. The mystic treats conceptual failure as an endpoint. The silence itself becomes the destination. Something deep must live there, humming quietly, just out of reach.

The deflationist treats the same failure as a transition. The silence is not sacred. It’s a signal. It means: this tool no longer fits; pick another or move on. Same breakdown. Entirely different posture.

Clearing space versus consecrating it

Much deflationary philosophy clears space. It removes assumptions that were doing illicit work and leaves behind something quieter, simpler, and occasionally disappointing.

Mysticism has a standing policy of consecrating cleared space. An empty room is never just empty. It must be pregnant with meaning. Absence becomes depth. Silence becomes revelation. The fewer claims you make, the more cosmic you must be.

This is not a philosophical disagreement so much as a difference in temperament. One side sees subtraction. The other experiences loss and rushes to compensate. Modern intellectual culture strongly prefers addition. New layers. Hidden structures. Further depths. Deflation feels like theft. So it gets reinterpreted as a subtler form of enrichment: Ah, fewer words, therefore more truth.

The aesthetic trap

There is also an aesthetic problem, which I increasingly suspect does most of the damage. Deflationary philosophy, when done well, tends to sound calm, patient, and restrained. It does not shout. It does not posture. It does not perform certainty. Unfortunately, this is exactly how profundity is supposed to sound.

Quiet seriousness is easily mistaken for spiritual depth. Refusal to speculate reads as wisdom. Negative definition acquires an apophatic glow. This is how one ends up being mistaken for a mystic without having said anything mystical at all.

A brief word about Wittgenstein (because of course)

This is not a new problem. Ludwig Wittgenstein spent a good portion of his career trying to convince people that philosophical problems arise when language goes on holiday. He was not pointing at a deeper reality beyond words. He was pointing back at the words and saying: look at what you’re doing with these.

Unfortunately, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent” has proven irresistible to those who think silence is where the real action is. Wittgenstein meant: stop here. Many readers heard: kneel here. This is the recurring fate of therapeutic philosophy. The cure gets mistaken for a sacrament.

Charity is not complicity

Another contributor to the confusion is tone. Deflationary work tends to be charitable. It explains why certain intuitions arise. It traces confusions to their sources. It does not sneer. This generosity is often misheard as validation. When you say, “It makes sense that we think this way,” some readers hear, “Your intuition is pointing at something profound.” You are offering an explanation. They are receiving an affirmation. At that point, no disclaimer will save you. Any denial is absorbed as further evidence that you are brushing up against something too deep to articulate.

The real disagreement

The disagreement here is not about reality. It is about what to do when explanation fails.

Mysticism treats failure as revelation. Deflation treats failure as diagnostic.

One sanctifies the breakdown. The other changes tools.

Once you see this, the repeated misfire stops being frustrating and starts being predictable.

A final, self-directed warning

There is, admittedly, a risk on the other side as well. Deflation can become mystical if it turns into ritual. If refusal hardens into identity. If “there is nothing there” becomes something one performs rather than concludes. Even subtraction can acquire ceremony if repeated without purpose. The discipline, such as it is, lies in knowing when to clear space—and when to leave the room.

No replacement gods

When a metaphysical idol is removed, someone will always ask what god is meant to replace it. The deflationary answer is often disappointing: none. This will never satisfy everyone. But the room is cleaner now, and that has its own quiet reward—even if someone insists on lighting incense in the corner.