Why shared language creates the illusion – not the reality – of shared experience

Human beings routinely assume that if another agent speaks our language, we have achieved genuine mutual understanding. Fluency is treated as a proxy for shared concepts, shared perceptual categories, and even shared consciousness. This assumption appears everywhere: in science fiction, in popular philosophy videos, and in everyday cross-cultural interactions. It is a comforting idea, but philosophically indefensible.

Recent discussions about whether one could ‘explain cold to an alien’ reveal how deeply this assumption is embedded. Participants in such debates often begin from the tacit premise that language maps transparently onto experience, and that if two interlocutors use the same linguistic term, they must be referring to a comparable phenomenon.

A closer analysis shows that this premise fails at every level.

Shared Language Does Not Imply Shared Phenomenology

Even within the human species, thermal experience is markedly variable. Individuals from colder climates often tolerate temperatures that visitors from warmer regions find unbearable. Acclimation, cultural norms, metabolic adaptation, and learned behavioural patterns all shape what ‘cold’ feels like.

If the same linguistic term corresponds to such divergent experiences within a species, the gap across species becomes unbridgeable.

A reptile, for example, regulates temperature not by feeling cold in any mammalian sense

A reptile, for example, regulates temperature not by feeling cold in any mammalian sense, but by adjusting metabolic output. A thermometer measures cold without experiencing anything at all. Both respond to temperature; neither inhabits the human category ‘cold’.

Thus, the human concept is already species-specific, plastic, and contextually learned — not a universal experiential module waiting to be translated.

Measurement, Behaviour, and Experience Are Distinct

Thermometers and reptiles react to temperature shifts, and yet neither possesses cold-qualia. This distinction illuminates the deeper philosophical point:

- Measurement registers a variable.

- Behaviour implements a functional response.

- Experience is a mediated phenomenon arising from a particular biological and cognitive architecture.

Aliens might measure temperature as precisely as any scientific instrument. That alone tells us nothing about whether they experience anything analogous to human ‘cold’, nor whether the concept is even meaningful within their ecology.

The Problem of Conceptual Export: Why Explanation Fails

Attempts to ‘explain cold’ to hypothetical aliens often jump immediately to molecular description – slower vibrational states, reduced kinetic energy, and so forth. This presumes that the aliens share:

- our physical ontology,

- our conceptual divisions,

- our sense-making framework,

- and our valuation of molecular explanation as intrinsically clarifying.

But these assumptions are ungrounded.

Aliens may organise their world around categories we cannot imagine. They may not recognise molecules as explanatory entities. They may not treat thermal variation as affectively laden or behaviourally salient. They may not even carve reality at scales where ‘temperature’ appears as a discrete variable.

When the conceptual scaffolding differs, explanation cannot transfer. The task is not translation but category creation, and there is no guarantee that the requisite categories exist on both sides.

The MEOW Framework: MEOWa vs MEOWb

The Mediated Encounter Ontology (MEOW) clarifies this breakdown by distinguishing four layers of mediation:

- T0: biological mediation

- T1: cognitive mediation

- T2: linguistic mediation

- T3: social mediation

Humans run MEOWa, a world structured through mammalian physiology, predictive cognition, metaphor-saturated language, and social-affective narratives.

Aliens (in fiction or speculation) operate MEOWb, a formally parallel mediation stack but with entirely different constituents.

Two systems can speak the same language (T2 alignment) whilst:

- perceiving different phenomena (T0 divergence),

- interpreting them through incompatible conceptual schemas (T1 divergence),

- and embedding them in distinct social-meaning structures (T3 divergence).

Linguistic compatibility does not grant ontological compatibility.

MEOWa and MEOWb allow conversation but not comprehension.

Fiction as Illustration: Why Aliens Speaking English Misleads Us

In Sustenance, the aliens speak flawless Standard Southern English. Their linguistic proficiency invites human characters (and readers) to assume shared meaning. Yet beneath the surface:

- Their sensory world differs;

- their affective architecture differs;

- their concepts do not map onto human categories;

- and many human experiential terms lack any analogue within their mediation.

The result is not communication but a parallel monologue: the appearance of shared understanding masking profound ontological incommensurability.

The Philosophical Consequence: No Universal Consciousness Template

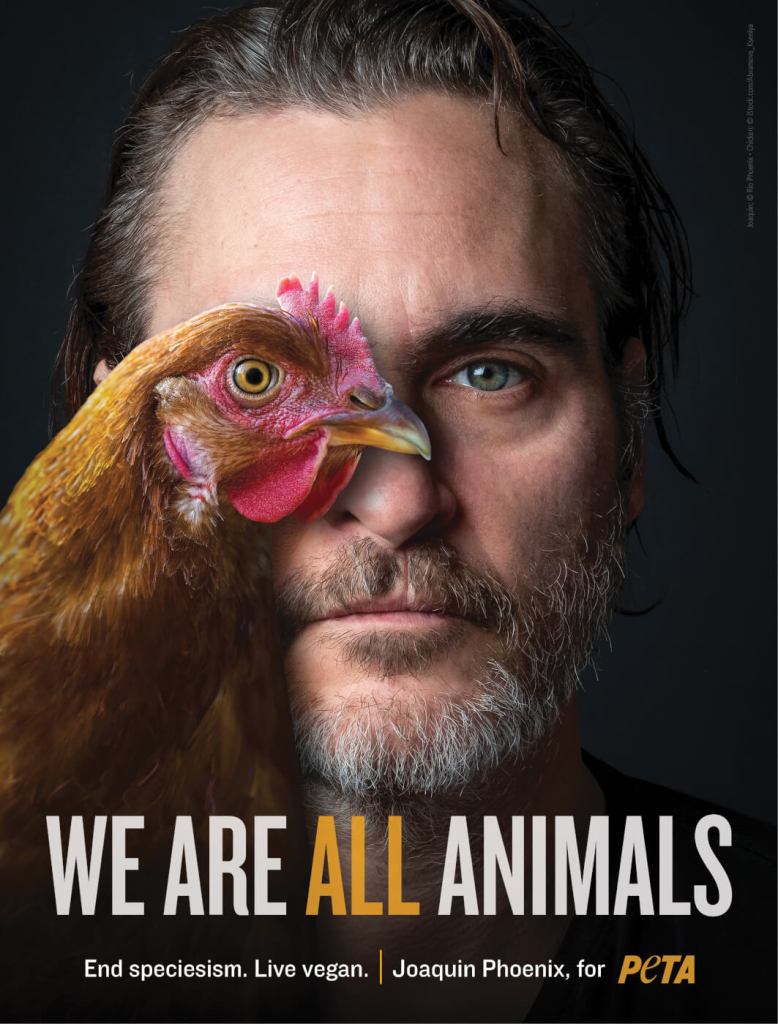

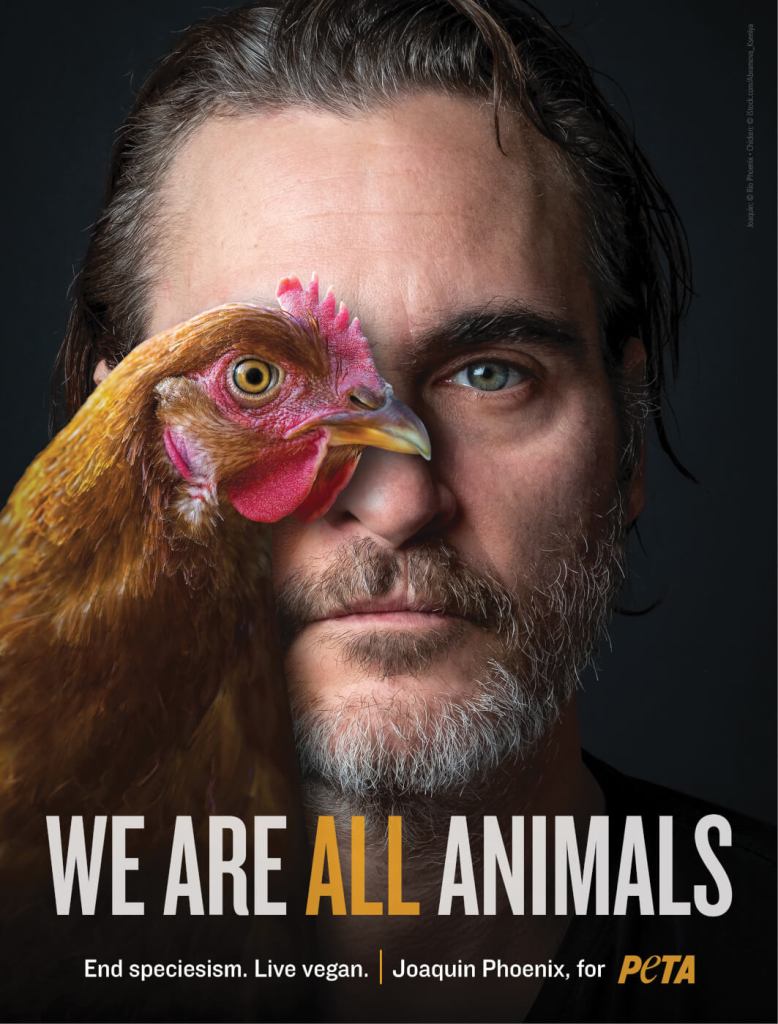

Underlying all these failures is a deeper speciesist assumption: that consciousness is a universal genus, and that discrete minds differ only in degree. The evidence points elsewhere.

If “cold” varies across humans, fails to apply to reptiles, and becomes meaningless for thermometers, then we have no grounds for projecting it into alien phenomenology. Nor should we assume that other species – biological or artificial – possess the same experiential categories, emotional valences, or conceptual ontologies that humans treat as foundational.

Consciousness is not a universal template awaiting instantiation in multiple substrates. It is a local ecological achievement, shaped by the mediations of the organism.

Conclusion

When aliens speak English, we hear familiarity and assume understanding. But a shared phonological surface conceals divergent sensory systems, cognitive architectures, conceptual repertoires, and social worlds.

Linguistic familiarity promises comprehension, but delivers only the appearance of it. The deeper truth is simple: Knowing our words is not the same as knowing our world.

And neither aliens, reptiles, nor thermometers inhabit the experiential space we map with those words.

Afterword

Reflections like these are precisely why my Anti-Enlightenment project exists. Much contemporary philosophical commentary remains quietly speciesist and stubbornly anthropomorphic, mistaking human perceptual idiosyncrasies for universal structures of mind. It’s an oddly provincial stance for a culture that prides itself on rational self-awareness.

To be clear, I have nothing against Alex O’Connor. He’s engaging, articulate, and serves as a gateway for many encountering these topics for the first time. But there is a difference between introducing philosophy and examining one’s own conceptual vantage point. What frustrates me is not the earnestness, but the unexamined presumption that the human experiential frame is the measure of all frames.

Having encountered these thought experiments decades ago, I’m not interested in posturing as a weary elder shaking his stick at the next generation. My disappointment lies elsewhere: in the persistent inability of otherwise intelligent thinkers to notice how narrow their perspective really is. They speak confidently from inside the human mediation stack without recognising it as a location – not a vantage point outside the world, but one local ecology among many possible ones.

Until this recognition becomes basic philosophical hygiene, we’ll continue to confuse linguistic familiarity for shared ontology and to mistake the limits of our own embodiment for the limits of consciousness itself.

![Quarks[1]](https://philosophics.blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/quarks1.png)