“Truths are illusions which we have forgotten are illusions.” — Nietzsche

Declaring the Problem

Most people say truth as if it were oxygen – obvious, necessary, self-evident. I don’t buy it.

Nietzsche was blunt: truths are illusions. My quarrel is only with how often we forget that they’re illusions.

Most people say truth as if it were oxygen – obvious, necessary, self-evident. I don’t buy it.

My own stance is unapologetically non-cognitivist. I don’t believe in objective Truth with a capital T. At best, I see truth as archetypal – a symbol humans invoke when they need to rally, persuade, or stabilise. I am, if you want labels, an emotivist and a prescriptivist: I’m drawn to problems because they move me, and I argue about them because I want others to share my orientation. Truth, in this sense, is not discovered; it is performed.

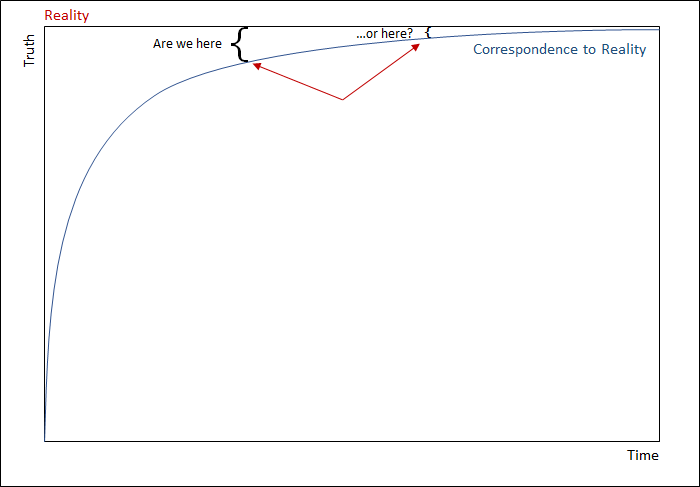

The Illusion of Asymptotic Progress

The standard story is comforting: over time, science marches closer and closer to the truth. Each new experiment, each new refinement, nudges us toward Reality, like a curve bending ever nearer to its asymptote.

This picture flatters us, but it’s built on sand.

Problem One: We have no idea how close or far we are from “Reality” on the Y-axis. Are we brushing against it, or still a light-year away? There’s no ruler that lets us measure our distance.

Problem Two: We can’t even guarantee that our revisions move us toward rather than away from it. Think of Newton and Einstein. For centuries, Newton’s physics was treated as a triumph of correspondence—until relativity reframed it as local, limited, provisional. What once looked like a step forward can later be revealed as a cul-de-sac. Our curve may bend back on itself.

Use Case: Newton, Einstein, and Gravity

Take gravity. For centuries, Newton’s laws were treated as if they had brought us into near-contact with Reality™—so precise, so predictive, they had to be true. Then Einstein arrives, reframes gravity not as a force but as the curvature of space-time, and suddenly Newton’s truths are parochial, a local approximation. We applauded this as progress, as if our asymptote had drawn tighter to Reality. But even Einstein leaves us with a black box: we don’t actually know what gravity is, only how to calculate its effects. Tomorrow another paradigm may displace relativity, and once again we’ll dutifully rebrand it as “closer to truth.” Progress or rhetorical re-baptism? The graph doesn’t tell us.

Thomas Kuhn was blunt about this: what we call “progress” is less about convergence and more about paradigm shifts, a wholesale change in the rules of the game. The Earth does not move smoothly closer to Truth; it lurches from one orthodoxy to another, each claiming victory. Progress, in practice, is rhetorical re-baptism.

Most defenders of the asymptotic story assume that even if progress is slow, it’s always incremental, always edging us closer. But history suggests otherwise. Paradigm shifts don’t just move the line higher; they redraw the entire curve. What once looked like the final step toward truth may later be recast as an error, a cul-de-sac, or even a regression. Newton gave way to Einstein; Einstein may yet give way to something that renders relativity quaint. From inside the present, every orthodoxy feels like progress. From outside, it looks more like a lurch, a stumble, and a reset.

If paradigm shifts can redraw the entire map of what counts as truth, then it makes sense to ask what exactly we mean when we invoke the word at all. Is truth a mirror of reality? A matter of internal coherence? Whatever works? Or just a linguistic convenience? Philosophy has produced a whole menu of truth theories, each with its own promises and pitfalls—and each vulnerable to the same problems of rhetoric, context, and shifting meanings.

The Many Flavours of Truth

Philosophers never tire of bottling “truth” in new vintages. The catalogue runs long: correspondence, coherence, pragmatic, deflationary, redundancy. Each is presented as the final refinement, the one true formulation of Truth, though each amounts to little more than a rhetorical strategy.

- Correspondence theory: Truth is what matches reality.

Problem: we can never measure distance from “Reality™” itself, only from our models. - Coherence theory: Truth is what fits consistently within a web of beliefs.

Problem: many mutually incompatible webs can be internally consistent. - Pragmatic theory: Truth is what works.

Problem: “works” for whom, under what ends? Functionality is always perspectival. - Deflationary / Minimalist: Saying “it’s true that…” adds nothing beyond the statement itself.

Problem: Useful for logic, empty for lived disputes. - Redundancy / Performative: “It is true that…” adds rhetorical force, not new content.

Problem: truth reduced to linguistic habit.

And the common fallback: facts vs. truths. We imagine facts as hard little pebbles anyone can pick up. Hastings was in 1066; water boils at 100°C at sea level. But these “facts” are just truths that have been successfully frozen and institutionalised. No less rhetorical, only more stable.

So truth isn’t one thing – it’s a menu. And notice: all these flavours share the same problem. They only work within language-games, frameworks, or communities of agreement. None of them delivers unmediated access to Reality™.

Truth turns out not to be a flavour but an ice cream parlour – lots of cones, no exit.

Multiplicity of Models

Even if correspondence weren’t troubled, it collapses under the weight of underdetermination. Quine and Duhem pointed out that any body of evidence can support multiple competing theories.

Hilary Putnam pushed it further with his model-theoretic argument: infinitely many models could map onto the same set of truths. Which one is “real”? There is no privileged mapping.

Conclusion: correspondence is undercut before it begins. Truth isn’t a straight line toward Reality; it’s a sprawl of models, each rhetorically entrenched.

Truth as Rhetoric and Power

This is where Orwell was right: “War is Peace, Freedom is Slavery, Ignorance is Strength.”

Truth, in practice, is what rhetoric persuades.

Michel Foucault stripped off the mask: truth is not about correspondence but about power/knowledge. What counts as truth is whatever the prevailing regime of discourse allows.

We’ve lived it:

- “The economy is strong”, while people can’t afford rent.

- “AI will save us”, while it mainly writes clickbait.

- “The science is settled” until the next paper unsettles it.

These aren’t neutral observations; they’re rhetorical victories.

Truth as Community Practice

Even when rhetoric convinces, it convinces in-groups. One group converges on a shared perception, another on its opposite. Flat Earth and Round Earth are both communities of “truth.” Each has error margins, each has believers, each perceives itself as edging toward reality.

Wittgenstein reminds us: truth is a language game. Rorty sharpens it: truth is what our peers let us get away with saying.

So truth is plural, situated, and always contested.

Evolutionary and Cognitive Scaffolding

Step back, and truth looks even less eternal and more provisional.

We spread claims because they move us (emotivism) and because we urge others to join (prescriptivism). Nietzsche was savage about it: truth is just a herd virtue, a survival trick.

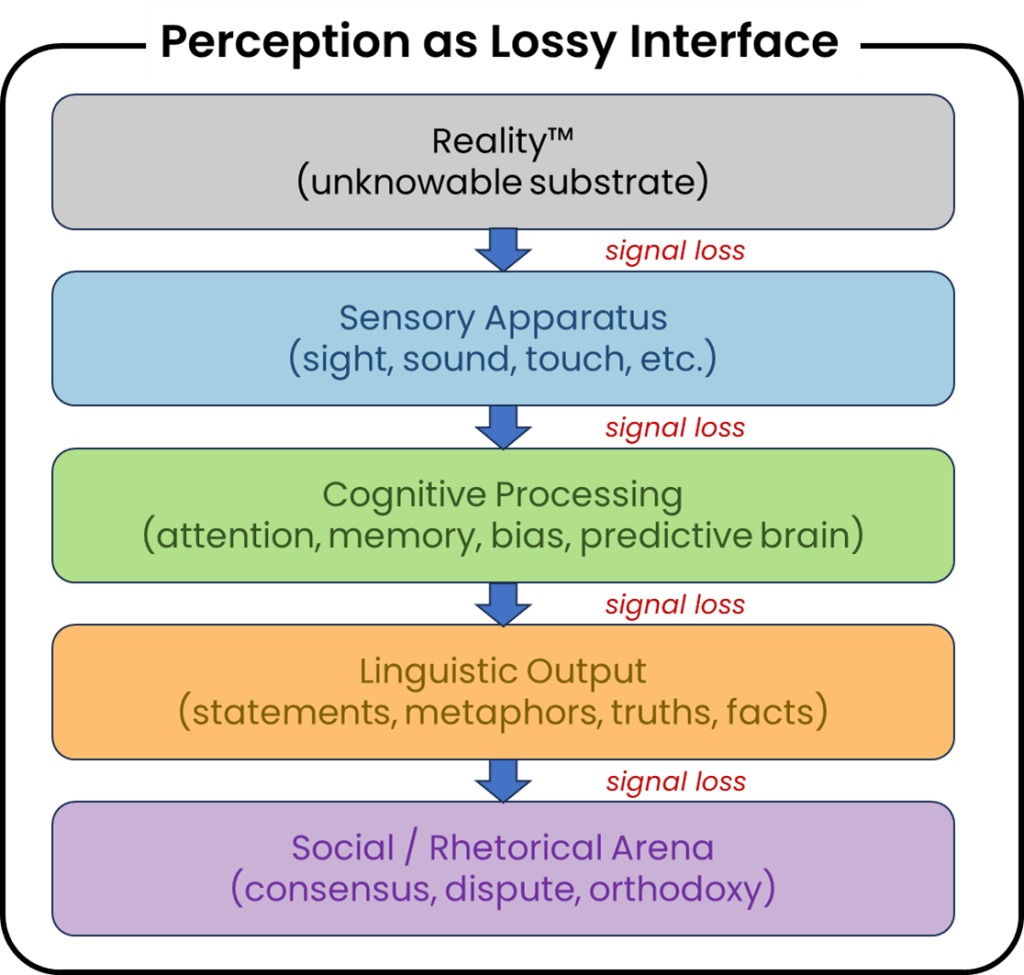

Cognitive science agrees, if in a different language: perception is predictive guesswork, riddled with biases, illusions, and shortcuts. Our minds don’t mirror reality; they generate useful fictions.

Archetypal Truth (Positive Proposal)

So where does that leave us? Not with despair, but with clarity.

Truth is best understood as archetypal – a construct humans rally around. It isn’t discovered; it is invoked. Its force comes not from correspondence but from resonance.

Here, my own Language Insufficiency Hypothesis bites hardest: all our truth-talk is approximation. Every statement is lossy compression, every claim filtered through insufficient words. We can get close enough for consensus, but never close enough for Reality.

Truth is rhetorical, communal, functional. Not absolute.

The Four Pillars (Manifesto Form)

- Archetypal – truth is a symbolic placeholder, not objective reality.

- Asymptotic – we gesture toward reality but never arrive.

- Rhetorical – what counts as truth is what persuades.

- Linguistically Insufficient – language guarantees slippage and error.

Closing

Nietzsche warned, Rorty echoed: stop fetishising Truth. Start interrogating the stories we tell in its name.

Every “truth” we now applaud may be tomorrow’s embarrassment. The only honest stance is vigilance – not over whether we’ve captured Reality™, but over who gets to decide what is called true, and why.

Truth has never been a mirror. It’s a mask. The only question worth asking is: who’s wearing it?