(Or: What I Learned When I Learned Nothing)

NB: This is the first of a parable triptych. Read part 2, The Tunnel.

Two valleys diverged in a mountain range, And sorry I could not travel both And be one traveller, long I stood And looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the undergrowth of reeds and optimism;

Then took the other, just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim, Because it was sandy and wanted wear— Though as for that, the passing there Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay In fog no step had trodden black. Oh, I kept the first for another day! Yet knowing how way leads on to way, I doubted if I should ever come back.

—Except I did come back. And I met someone coming the other way. And we stood there in the clouds like a pair of idiots trying to explain our respective valleys using the same words for completely different things.

Here’s what they don’t tell you about Frost’s poem: the two paths were “really about the same.” He says it right there in the text. The divergence happens retroactively, in the telling, when he sighs and claims “that has made all the difference.”

But he doesn’t know that yet. He can’t know that. The paths only diverge in memory, once he’s committed to one and cannot check the other.

Here’s what they don’t tell you about political disagreement: it works the same way.

The Actual Story (Minus the Versification)

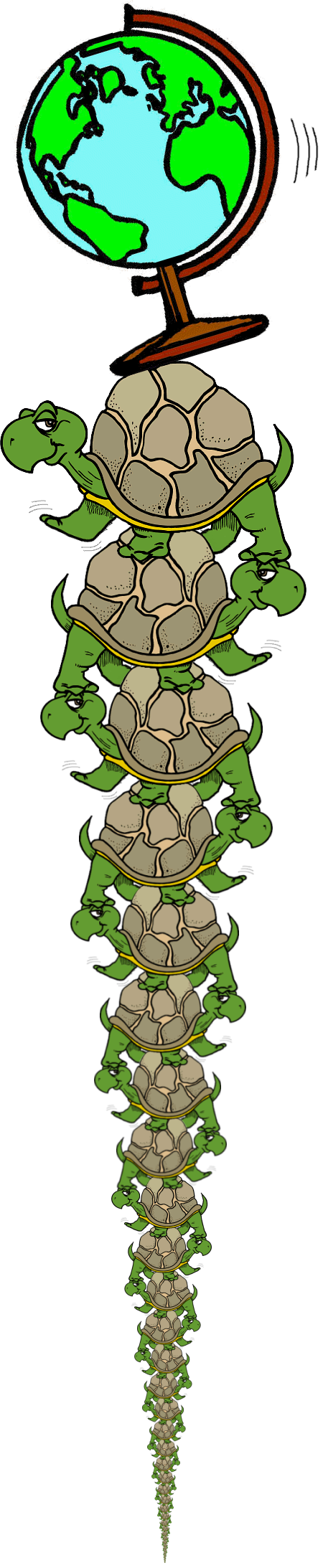

Once upon a time—and I’m going to need you to suspend your allergy to fairy tales for about eight minutes—there was one settlement. One people. One language. One lake with drinkable water and fish that cooperated by swimming in schools.

Then mountains happened. Slowly. No dramatic rupture, no war, no evil king. Just tectonics doing what tectonics does, which is ruin everyone’s commute.

The people on one side kept the lake. The people on the other side got a rain shadow and a lot of bloody sand.

Both sides adapted. Rationally. Reasonably. Like competent humans responding to actual material conditions.

Lake people: “There’s enough water. Let’s experiment. Let’s move around. Let’s try things.”

Desert people: “There is definitely not enough water. Let’s ration. Let’s stay put. Let’s not waste things.”

Neither wrong. Neither irrational. Just oriented differently because the ground beneath them had literal different moisture content.

The Bit Where It Gets Interesting

Centuries later, two people—one from each side—decide to climb the mountains and meet at the top.

Why? I don’t know. Curiosity. Stupidity. The desire to write a tedious blog post about epistemology.

They meet in the fog. They speak the same language. Grammar intact. Vocabulary functional. Syntax cooperative.

And then one tries to explain “reeds.”

“Right, so we have these plants that grow really fast near the water, and we have to cut them back because otherwise they take over—”

“Sorry, cut them back? You have too much plant?”

“Well, yes, they grow quite quickly—”

“Why would a plant grow quickly? That sounds unsustainable.”

Meanwhile, the other one tries to explain “cactus.”

“We have these plants with spines that store water inside for months—”

“Store water for months? Why doesn’t the plant just… drink when it’s thirsty?”

“Because there’s no water to drink.”

“But you just said the plant is full of water.”

“Yes. Which it stored. Previously. When there was water. Which there no longer is.”

“Right. So… hoarding?”

You see the problem.

Not stupidity. Not bad faith. Not even—and this is the part that will annoy people—framing.

They can both see perfectly well. The fog prevents them from seeing each other’s valleys, but that’s almost beside the point. Even if the fog lifted, even if they could point and gesture and show each other their respective biomes, the fundamental issue remains:

A cactus is a good solution to a problem the lake-dweller doesn’t have.

A reed is a good solution to a problem the desert-dweller doesn’t have.

Both are correct. Both are adaptive. Both would be lethal if transplanted.

The Retreat (Wherein Nothing Is Learned)

They part amicably. No shouting. No recriminations. Both feel they explained themselves rather well, actually.

As they descend back into their respective valleys, each carries the same thought:

“The other person seemed reasonable. Articulate, even. But their world is completely unworkable and if we adopted their practices here, people would die.”

Not hyperbole. Actual environmental prediction.

If the lake people adopted desert-logic—ration everything, control movement, assume scarcity—they would strangle their own adaptability in a context where adaptability is the whole point.

If the desert people adopted lake-logic—explore freely, trust abundance, move without restraint—they would exhaust their resources in a context where resources are the whole point.

The Bit Where I Connect This to Politics (Because Subtlety Is Dead)

So when someone tells you that political disagreement is just a matter of perspective, just a failure of empathy, just a problem of framing—

Ask them this:

Do the two valleys become the same valley if both sides squint really hard?

Does the desert get wetter if you reframe scarcity as “efficiency”?

Does the lake dry up if you reframe abundance as “waste”?

No?

Then perhaps the problem is not that people are choosing the wrong lens.

Perhaps the problem is that they are standing in different material conditions, have adapted rational survival strategies to those conditions, and are now shouting advice at each other that would be lethal if followed.

The lake-dweller says: “Take risks! Explore! There’s enough!”

True. In a lake biome. Suicidal in a desert.

The desert-dweller says: “Conserve! Protect! Ration!”

True. In a desert biome. Suffocating near a lake.

Same words. Different worlds. No amount of dialogue makes water appear in sand.

The Frostian Coda (With Apologies to New England)

I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two valleys diverged on a mountainside, and I— I stood in the fog and tried to explain reeds to someone who only knew cactus, And that has made… well, no difference at all, actually.

We’re still shouting across the mountains.

We still think the other side would be fine if only they’d listen.

We still use the same words for utterly different referents.

And we still confuse “I explained it clearly” with “explanation bridges material conditions.”

Frost was right about one thing: way leads on to way.

The valleys keep diverging.

The fog doesn’t lift.

And knowing how mountains work, I doubt we’ll meet again.

Moral: If your political metaphor doesn’t account for actual rivers, actual deserts, and actual fog, it’s not a metaphor. It’s a fairy tale. And unlike fairy tales, this one doesn’t end with reunion.

It ends with two people walking home, each convinced the other is perfectly reasonable and completely unsurvivable.

Which, if you think about it, is far more terrifying than simple disagreement.

Read part 2 of 3, The Tunnel.