One Motor Vehicle

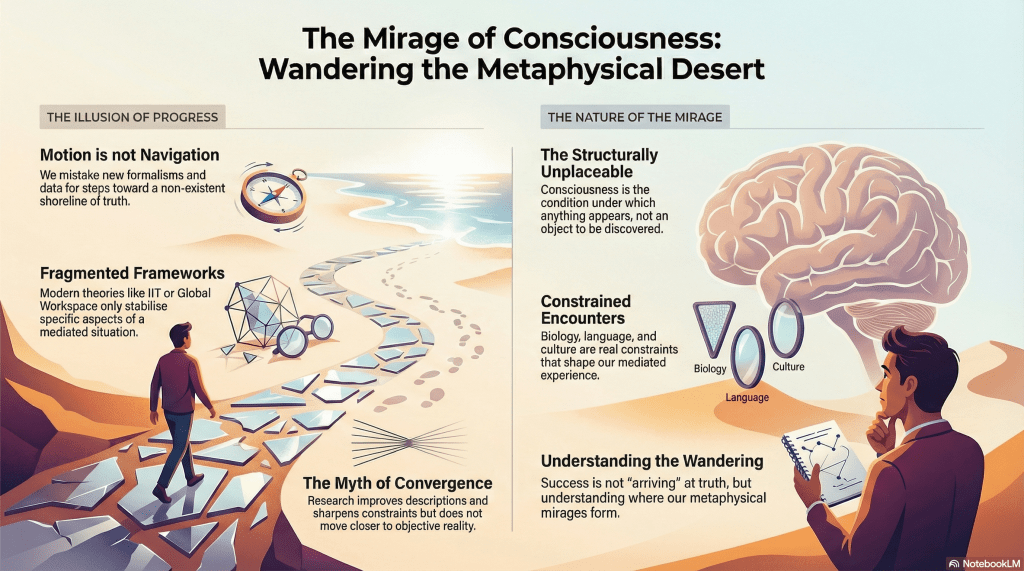

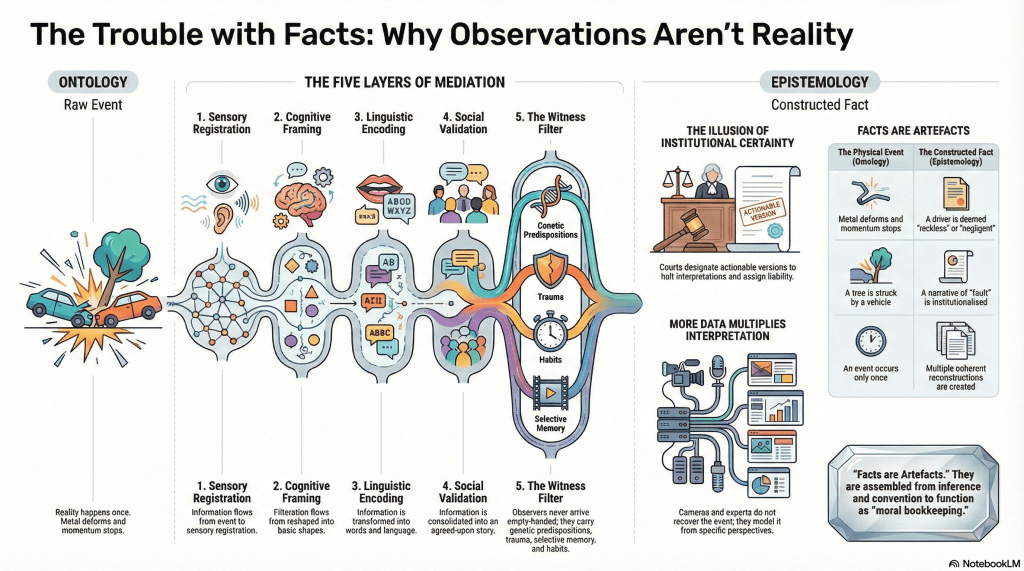

What we call facts are not discoveries of an unfiltered world. They are the end-products of mediation.

Let’s walk through an example.

Apparently, a motor vehicle has collided with a tree. Trees are immobile objects, so we can safely rule out the tree colliding with the car.*

So what, exactly, are the facts?

Ontology (the boring bit)

Ontologically, something happened.

A car struck a tree.

Metal deformed.

Momentum stopped.

Reality did not hesitate. It did not consult witnesses. It did not await interpretation.

This is the part Modernity likes to gesture at reverently before immediately leaving it behind.

The Witness

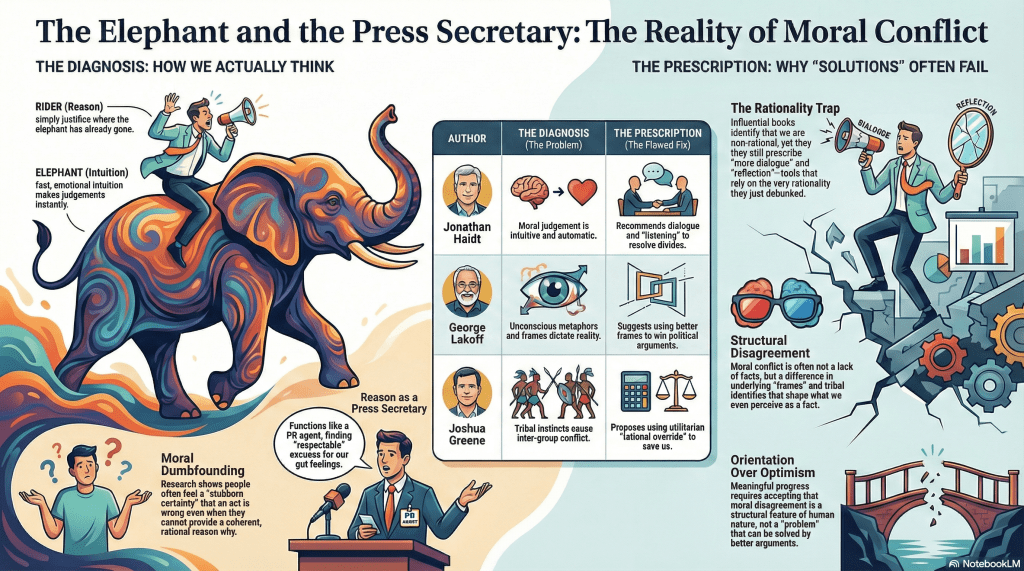

Even the driver does not enjoy privileged access to “what really happened”.

They get:

- proprioceptive shock

- adrenaline distortion

- attentional narrowing

- selective memory

- post hoc rationalisation

- possibly a concussion

Which is already several layers deep before language even arrives to finish the job.

We can generalise the structure:

event → sensory registration → cognitive framing → linguistic encoding → social validation

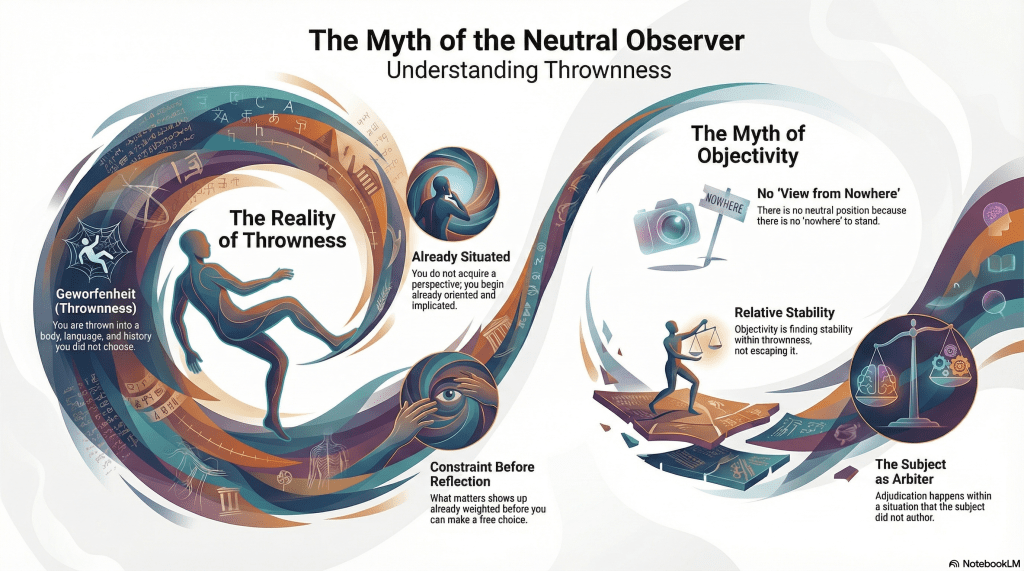

Ontology: events occur. States of affairs obtain. Something happens whether or not we notice.

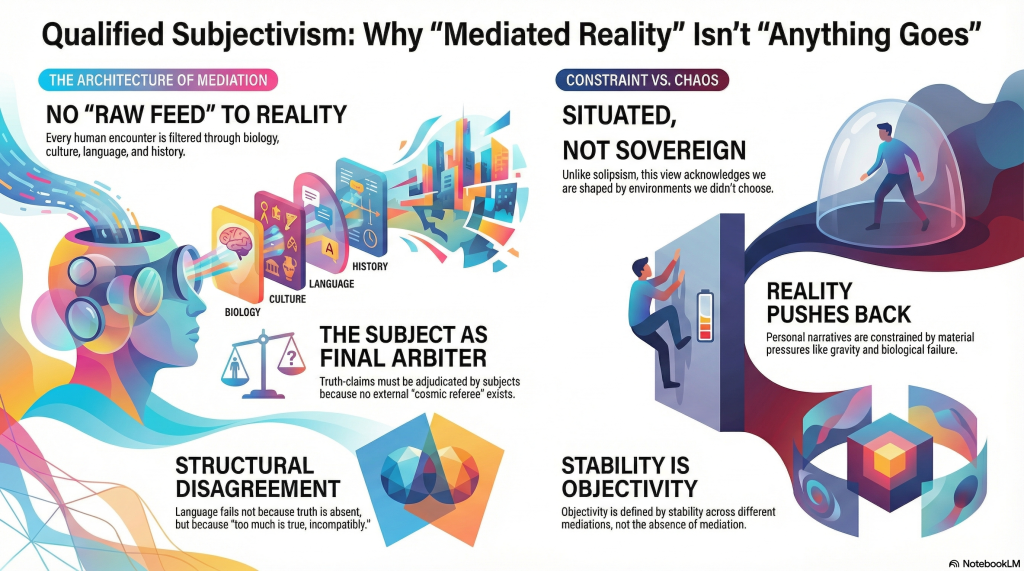

Epistemology: observation is always filtered through instruments, concepts, language, habits, and incentives.

Modern sleight of hand: collapse the second into the first and call the result the facts.

People love the phrase “hard facts”, as if hardness transfers from objects to propositions by osmosis. It doesn’t. The tree is solid. The fact is not.

Facts are artefacts. They are assembled from observation, inference, convention, and agreement. They function. They do not reveal essence.

Reality happens once. Facts happen many times, differently, depending on who needs them and why.

Filtration

An event occurred. A car struck a tree.

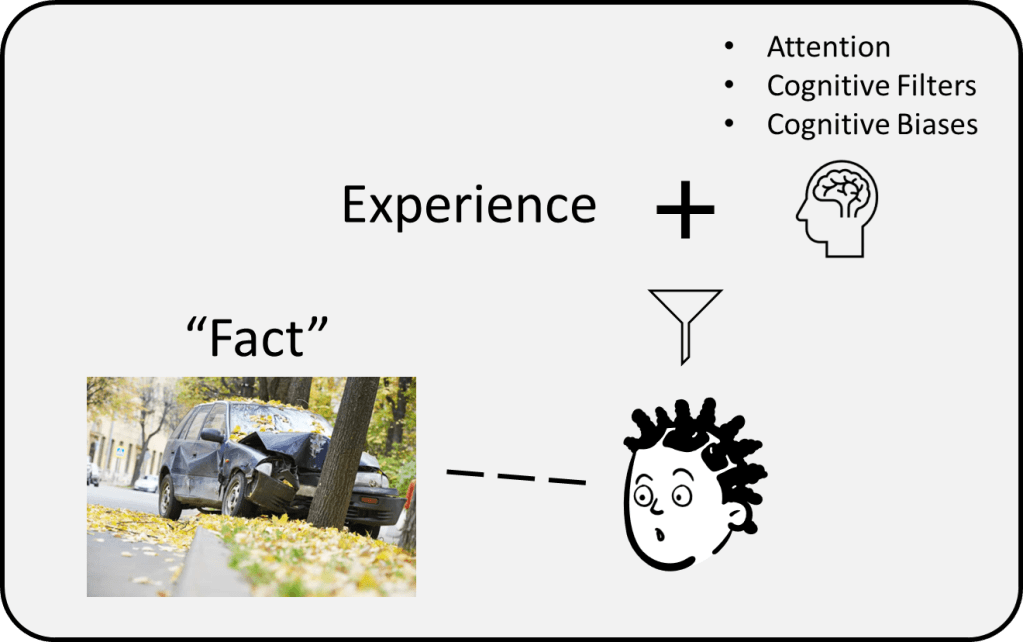

Then an observer arrives. But observers never arrive empty-handed.

They arrive with history: genetics, upbringing, trauma, habits, expectations, incentives. They arrive already filtered.

Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass Sunstein spend an entire book explaining just how unreliable this process is. See Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment if you want the empirical receipts.

- Even before bias enters, attention does.

- When did the observer notice the crash?

- At the sound? At the sight? After the fact?

- Were they already looking, or did the noise interrupt something else entirely?

Reality happens once. Facts happen many times, differently, depending on who needs them and why.

Here Comes the Law

This is where the legal system enters, not because truth has been found, but because closure is required.

Courts do not discover facts. They designate versions of events that are good enough to carry consequences. They halt the cascade of interpretations by institutional force and call the result justice.

At every epistemic level, what we assert are interpretations of fact, never access to ontological essence.

Intent, negligence, recklessness. These are not observations. They are attributions. They are stopping rules that allow systems to function despite uncertainty.

The law does not ask what really happened.

It asks which story is actionable.

Two Motor Vehicles

Now add a second moving object.

Another car enters the frame, and with it an entire moral universe.

Suddenly, the event is no longer merely physical. It becomes relational. Agency proliferates. Narratives metastasise.

Who was speeding?

Who had the right of way?

Who saw whom first?

Who should have anticipated whom?

Intent and motive rush in to fill the explanatory vacuum, despite remaining just as unobservable as before.

Nothing about the ontology improved.

Everything about the storytelling did.

Where the tree refused intention, the second vehicle invites it. We begin inferring states of mind from trajectories, attributing beliefs from brake lights, extracting motives from milliseconds of motion.

But none of this is observed.

What we observe are:

- vehicle positions after the fact,

- damage patterns,

- skid marks,

- witness statements already filtered through shock and expectation.

From these traces, we construct mental interiors.

The driver “intended” to turn.

The other driver “failed” to anticipate.

Someone was “reckless”.

Someone else was merely “unlucky”.

These are not facts. They are interpretive assignments, layered atop already mediated observations, selected because they allow responsibility to be distributed in socially recognisable ways.

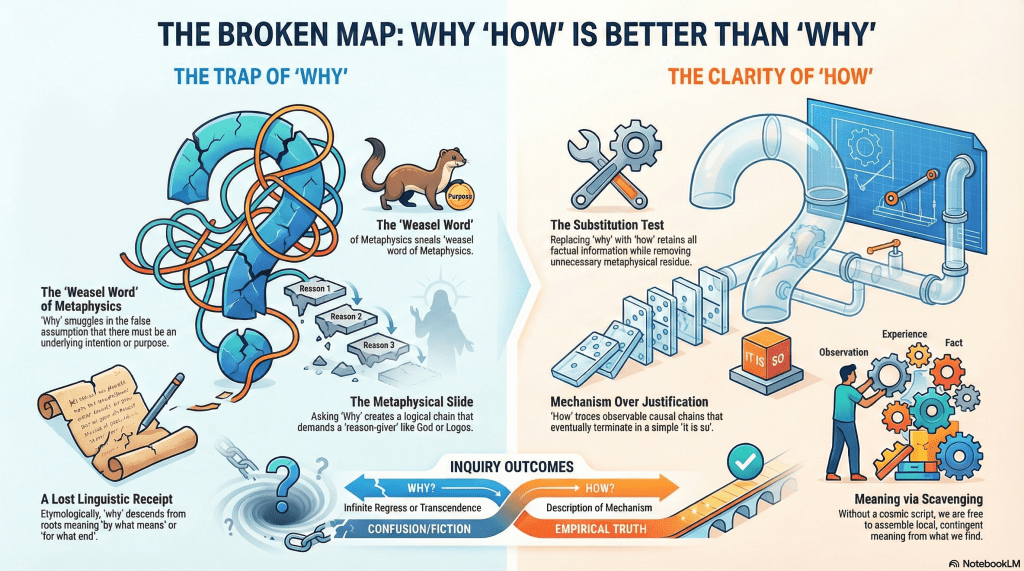

This is why explanation now fractures.

One cascade of whys produces a story about distraction or poor judgment.

Another produces a story about road design or visibility.

Another about timing, traffic flow, or urban planning.

Each narrative is plausible.

Each is evidence-constrained.

None is ontologically privileged.

Yet one will be chosen.

Not because it is truer, but because it is actionable.

The presence of a second vehicle does not clarify causation. It merely increases the number of places we are willing to stop asking questions.

Modernity mistakes this proliferation of narrative for epistemic progress. In reality, it is moral bookkeeping.

The crash still occurred.

Metal still deformed.

Momentum still stopped.

What changed was not access to truth, but the urgency to assign fault.

With one vehicle and a tree, facts already fail to arrive unmediated.

With two vehicles, mediation becomes the point.

And still, we insist on calling the result the facts.

Many Vehicles, Cameras, and Experts

At this point, Modernity regains confidence.

Add more vehicles.

Add traffic cameras.

Add dashcams, CCTV, bodycams.

Add accident reconstruction experts, engineers, psychologists, statisticians.

Surely now we are approaching the facts.

But nothing fundamental has changed. We have not escaped mediation. We have merely scaled it up and professionalised it.

Cameras do not record reality. They record:

- a frame,

- from a position,

- at a sampling rate,

- with compression,

- under lighting conditions,

- interpreted later by someone with a mandate.

Video feels decisive because it is vivid, not because it is ontologically transparent. It freezes perspective and mistakes that freeze for truth. Slow motion, zoom, annotation. Each step adds clarity and distance at the same time.

Experts do not access essence either. They perform disciplined abduction.

From angles, debris fields, timing estimates, and damage profiles, they infer plausible sequences. They do not recover the event. They model it. Their authority lies not in proximity to reality, but in institutional trust and methodological constraint.

More data does not collapse interpretation.

It multiplies it.

With enough footage, we don’t get the story. We get competing reconstructions, each internally coherent, each technically defensible, each aligned to a different question:

- Who is legally liable?

- Who is financially responsible?

- Who violated policy?

- Who can be blamed without destabilising the system?

At some point, someone declares the evidence “clear”.

What they mean is: we have enough material to stop arguing.

This is the final Modern illusion: that accumulation converges on essence. In reality, accumulation converges on closure.

The event remains what it always was: inaccessible except through traces.

The facts become thicker, more confident, more footnoted.

Their metaphysical status does not improve.

Reality happened once. It left debris. We organised the debris into narratives that could survive institutions.

Cameras didn’t reveal the truth. Experts didn’t extract it. They helped us agree on which interpretation would count.

And agreement, however necessary, has never been the same thing as access to what is.

* I was once driving in a storm, and a telephone pole fell about a metre in front of my vehicle. My car drove over the pole, and although I was able to drive the remainder of the way home, my suspension and undercarriage were worse for the wear and tear.