How retribution stays upright by not being examined

There is a persistent belief that our hardest disagreements are merely technical. If we could stop posturing, define our terms, and agree on the facts, consensus would emerge. This belief survives because it works extremely well for birds and tables.

It fails spectacularly for justice.

The Language Insufficiency Hypothesis (LIH) isn’t especially interested in whether people disagree. It’s interested in how disagreement behaves under clarification. With concrete terms, clarification narrows reference. With contested ones, it often fractures it. The more you specify, the more ontologies appear.

Justice is the canonical case.

Retributive justice is often presented as the sober, adult conclusion. Not emotional. Not ideological. Just what must be done. In practice, it is a delicately balanced structure built out of other delicately balanced structures. Pull one term away and people grow uneasy. Pull a second and you’re accused of moral relativism. Pull a third and someone mentions cavemen.

Let’s do some light demolition. I created a set of 17 Magic: The Gathering-themed cards to illustrate various concepts. Below are a few. A few more may appear over time.

Card One: Choice

The argument begins innocently enough:

They chose to do it.

But “choice” here is not an empirical description. It’s a stipulation. It doesn’t mean “a decision occurred in a nervous system under constraints.” It means a metaphysically clean fork in the road. Free of coercion, history, wiring, luck, trauma, incentives, or context.

That kind of choice is not discovered. It is assumed.

Pointing out that choices are shaped, bounded, and path-dependent does not refine the term. It destabilises it. Because if choice isn’t clean, then something else must do the moral work.

Enter the next card.

Card Two: Agency

Agency is wheeled in to stabilise choice. We are reassured that humans are agents in a morally relevant sense, and therefore choice “counts”.

Counts for what, exactly, is rarely specified.

Under scrutiny, “agency” quietly oscillates between three incompatible roles:

- a descriptive claim: humans initiate actions

- a normative claim: humans may be blamed

- a metaphysical claim: humans are the right kind of cause

These are not the same thing. Treating them as interchangeable is not philosophical rigour. It’s semantic laundering.

But agency is emotionally expensive to question, so the discussion moves on briskly.

Card Three: Responsibility

Responsibility is where the emotional payload arrives.

To say someone is “responsible” sounds administrative, even boring. In practice, it’s a moral verdict wearing a clipboard.

Watch the slide:

- causal responsibility

- role responsibility

- moral responsibility

- legal responsibility

One word. Almost no shared criteria.

By the time punishment enters the picture, “responsibility” has quietly become something else entirely: the moral right to retaliate without guilt.

At which point someone will say the magic word.

Card Four: Desert

Desert is the most mystical card in the deck.

Nothing observable changes when someone “deserves” punishment. No new facts appear. No mechanism activates. What happens instead is that a moral permission slip is issued.

Desert is not found in the world. It is declared.

And it only works if you already accept a very particular ontology:

- robust agency

- contra-causal choice

- a universe in which moral bookkeeping makes sense

Remove any one of these and desert collapses into what it always was: a story we tell to make anger feel principled.

Which brings us, finally, to the banner term.

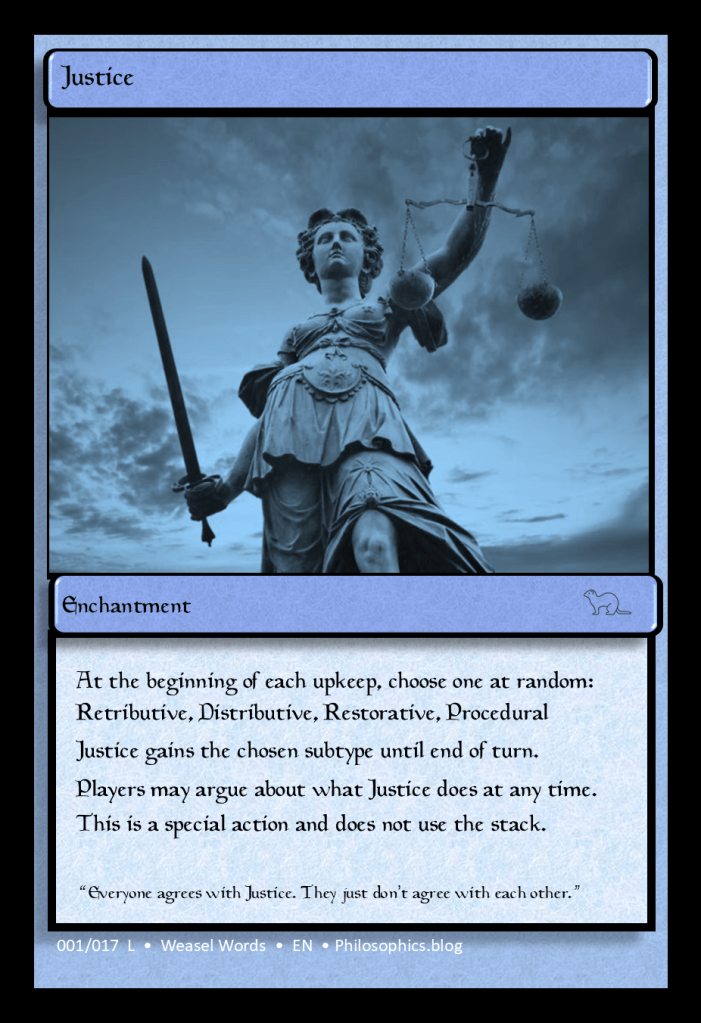

Card Five: Justice

At this point, justice is invoked as if it were an independent standard hovering serenely above the wreckage.

It isn’t.

“Justice” here does not resolve disagreement. It names it.

Retributive justice and consequentialist justice are not rival policies. They are rival ontologies. One presumes moral balance sheets attached to persons. The other presumes systems, incentives, prevention, and harm minimisation.

Both use the word justice.

That is not convergence. That is polysemy with a body count.

Why clarification fails here

This is where LIH earns its keep.

With invariants, adding detail narrows meaning. With terms like justice, choice, responsibility, or desert, adding detail exposes incompatible background assumptions. The disagreement does not shrink. It bifurcates.

This is why calls to “focus on the facts” miss the point. Facts do not adjudicate between ontologies. They merely instantiate them. If agency itself is suspect, arguments for retribution do not fail empirically. They fail upstream. They become non sequiturs.

This is also why Marx remains unforgivable to some.

“From each according to his ability, to each according to his need” isn’t a policy tweak. It presupposes a different moral universe. No amount of clarification will make it palatable to someone operating in a merit-desert ontology.

The uncomfortable conclusion

The problem is not that we use contested terms. We cannot avoid them.

The problem is assuming they behave like tables.

Retributive justice survives not because it is inevitable, but because its supporting terms are treated as settled when they are anything but. Each card looks sturdy in isolation. Together, they form a structure that only stands if you agree not to pull too hard.

LIH doesn’t tell you which ontology to adopt.

It tells you why the argument never ends.

And why, if someone insists the issue is “just semantic”, they’re either confused—or holding the deck.