In the last post, I argued that the so-called ‘hard problem of consciousness‘ was never a problem with consciousness. It was a problem with language – specifically, the English language’s unfortunate habit of carving the world into neat little substances and then demanding to know why its own divisions won’t glue back together.

The response was predictable.

- ‘But what about subjective feel?’

- ‘What about emergence?’

- ‘What about ontology?’

- ‘What about Chalmers?’

- ‘What about that ineffable thing you can’t quite point at?’

All fair questions. All built atop the very framing that manufactures the illusion of a metaphysical gap.

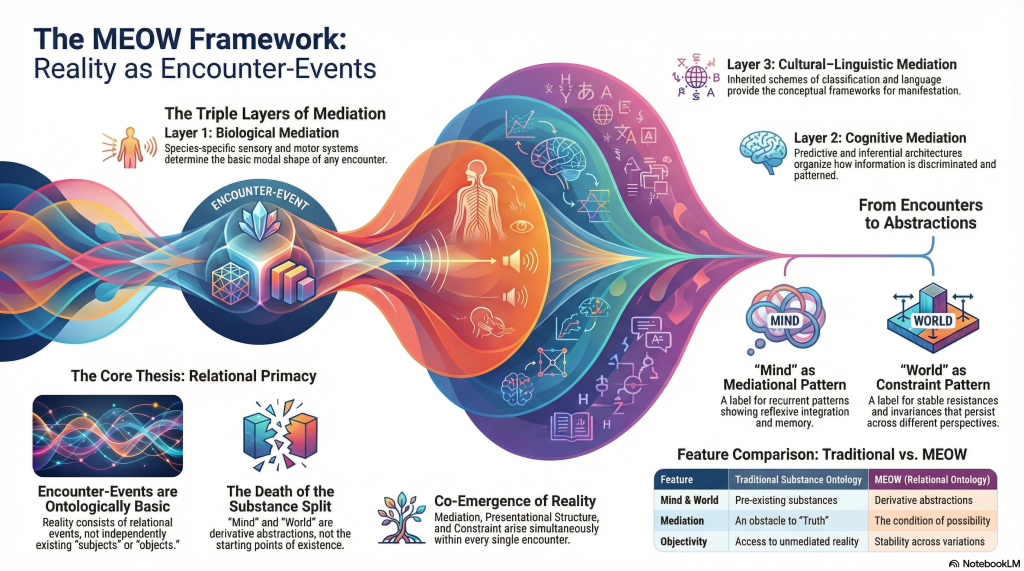

So here’s the promised demonstration: not yet a full essay (though it may evolve into one), but a clear application of MEOW – the Mediated Encounter Ontology of the World – to the hard problem itself. Consider this a field test of the framework. A tidy autopsy, not the funeral oration.

The Set-Up: Chalmers’ Famous Trick

Chalmers asks:

How do physical processes give rise to experience?

The question feels profound only because the terms ‘physical’ and ‘experience’ smuggle in the very metaphysics they pretend to interrogate. They look like opposites because the grammar makes them opposites. English loves a comforting binary.

But MEOW doesn’t bother with the front door. It doesn’t assume two substances – ‘mind’ over here, ‘world’ over there – and then panic when they refuse to shake hands. It treats experience as the way an encounter manifests under a layered architecture of mediation. There’s no bridge. Only layers.

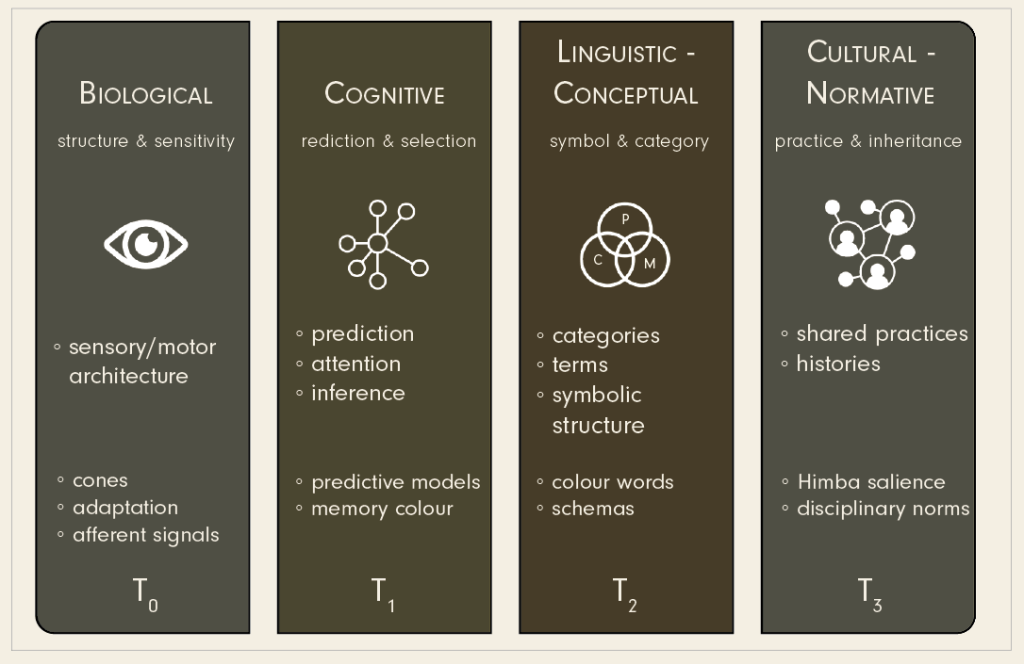

T₀ – Biological Mediation

The body is not a barrier. It is the encounter’s first architecture.

At T₀, the world is already transformed: transduction, gating, synchrony, inhibition, adaptation. Organisms don’t receive ‘raw’ physical inputs. They metabolise them. The form of contact is biological before it is anything else.

The hard problem begins by assuming there’s a realm of dumb physical mechanisms that somehow need to ‘produce’ experience. But organisms do not encounter dumb mechanism. They encounter structured contact –biological mediation – from the first millisecond.

If you insist on thinking in substances, T₀ looks like a problem.

If you think in mediations, it looks like the beginning of sense-making.

T₁ – Cognitive Mediation

Where the Enlightenment saw a window, cognition installs a newsroom.

Prediction, priors, memory, inference, attention – all shaping what appears and what never makes it into view. Experience at T₁ is not something ‘added’. It is the organisational structure of the encounter itself.

The hard problem treats ‘experience’ as a mysterious extra–something floating atop neural activity like metaphysical cream. But at T₁, what appears as experience is simply the organisation of biological contact through cognitive patterns.

There is no ‘what emerges from the physical’. There is the way the encounter is organised.

And all of this unfolds under resistance – the world’s persistent refusal to line up neatly with expectation. Prediction errors, perceptual limits, feedback misfires: this constraint structure prevents the entire thing from collapsing into relativist soup.

T₂ – Linguistic–Conceptual Mediation

Here is where the hard problem is manufactured.

This is the layer that takes an ordinary phenomenon and turns it into a metaphysical puzzle. Words like ‘experience’, ‘physical’, ‘mental’, ‘subjective’, and ‘objective’ pretend to be carved in stone. They aren’t. They slide, drift, and mutate depending on context, grammar, and conceptual lineage.

The hard problem is almost entirely a T₂ artefact – a puzzle produced by a grammar that forces us to treat ‘experience’ and ‘physical process’ as two different substances rather than two different summaries of different mediational layers.

If you inherit a conceptual architecture that splits the world into mind and matter, of course you will look for a bridge. Language hands you the illusion and then refuses to refund the cost of admission.

T₃ – Cultural–Normative Mediation

The Western problem is not the world’s problem.

The very idea that consciousness is metaphysically puzzling is the product of a specific cultural lineage: Enlightenment substance dualism (even in its ‘materialist’ drag), Cartesian leftovers, empiricist habits, and Victorian metaphysics disguised as objectivity.

Other cultures don’t carve the world this way. Other ontologies don’t need to stitch mind back into world. Other languages simply don’t produce this problem.

The hard problem is not a universal insight. It’s a provincial glitch.

Reassembling the Encounter

Once you run consciousness through the mediational layers, the hard problem dissolves:

- Consciousness is not an emergent property of neural complexity.

- Consciousness is not a fundamental property of the universe.

- Consciousness is the reflexive mode of certain mediated encounters, the form the encounter takes when cognition, language, and culture become part of what is appearing.

There is no gap to explain because the ‘gap’ is the product of a linguistic–conceptual framework that splits where the world does not.

As for the ever-mystical ‘what-it’s-like’: that isn’t a metaphysical jewel buried in the brain; it is the way a T₀–T₃ architecture manifests when its own structure becomes reflexively available.

A Brief Disclaimer Before the Internet Screams

Pointing out that Chalmers (and most of modern philosophy) operates within a faulty ontology is not to claim MEOW is flawless or final. It isn’t. But if Occam’s razor means anything, MEOW simply removes one unnecessary supposition — the idea that ‘mind’ and ‘world’ are independent substances in need of reconciliation. No triumphalism. Just subtraction.

Where This Leaves Chalmers

Chalmers is not wrong. He’s just asking the wrong question. The hard problem is not a metaphysical insight. It’s the moment our language tripped over its shoelaces and insisted the pavement was mysterious.

MEOW doesn’t solve the hard problem. It shows why the hard problem only exists inside a linguistic architecture that can’t model its own limitations.

This piece could easily grow into a full essay – perhaps it will. But for now, it does the job it needs to: a practical demonstration of MEOW in action.

And, arguably more important, it buys me one more day of indexing.