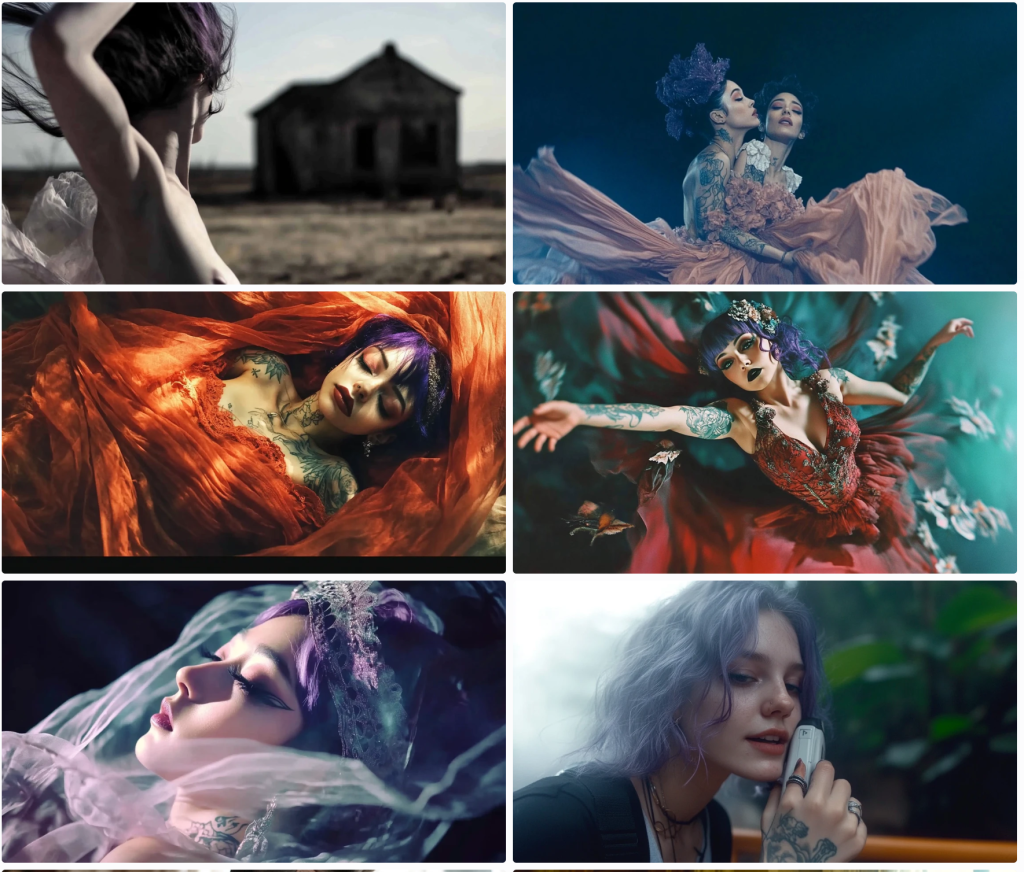

As some of you know, I publish speculative fiction under the name Ridley Park. Propensity is one of several recent releases – a novella that leans philosophical, brushes up against literary fiction, and steps quietly into the margins of sci-fi.

It’s not about spaceships or superintelligence. It’s about modulation.

About peace engineered through neurochemical compliance.

About the slow horror of obedience without belief, and the behavioural architecture that lets us think we’re still in control.

The ideas explored include:

- Free will as illusion

- Peace as compliance

- Drift, echo, and the limits of modulation

- Obedience without belief

- Institutional horror and soft dystopia

- Consent and behavioural control

- Narrative as residue

- Collapse by calibration

Though filed under speculative fiction, Propensity [US] is best read as a literary artefact – anti-sci-fi, in a sense. There’s no fetishisation of technology or progress. Just modulation, consequence, and the absence of noise.

This PDF contains selected visual excerpts from the physical book to accompany the free audiobook edition. For readers and listeners alike, it offers a glimpse into Ridley Park’s world – a quietly dystopian, clinically unsettling, and depressingly plausible one.

- Title page

- Copyrights page

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 10: Memorandum. This chapter is read in the audiobook. The inclusion here is for visualisation as it is rendered in the form of a memo.

- Chapter 26: Simulacra. This chapter is read in the audiobook. The inclusion here is for visualisation as it is rendered in the format of a screenplay.

- Chapter 28: Standard Test: This chapter is read in the audiobook. The inclusion here is for visualisation as it is rendered in the format of a standardised test.

- Chapter 34: Calendar. This chapter is read in the audiobook. The inclusion here is for visualisation as it is rendered in the format of a calendar.

- Chapter 39: Carnage. This chapter is read in the audiobook. The inclusion here is for visualisation as it is rendered in the form of a Dr Suess-type poem.

- Chapter 41: Leviathan. This chapter is excerpted in the audiobook. The inclusion here is for visualisation as it is rendered with an image of the cover of Hobbes’ Leviathan and redacted page content.

- Chapter 42: Ashes to Ashes. This chapter is read in the audiobook. The inclusion here is for visualisation as it is rendered in the form of text art.

- Chapter 43: Unknown. A description of this chapter is read in the audiobook. The inclusion here is for visualisation as it is rendered in the form of an ink sketch.

- Chapter 44: Vestige. A description of this chapter is read in the audiobook. The inclusion here is for visualisation as it is rendered in the form of text art.

For more information about Ridley Park’s Propensity, visit the website. I’ll be sharing content related to Propensity and my other publications. I’ll cross-post here when the material has a philosophical bent, which it almost always does.