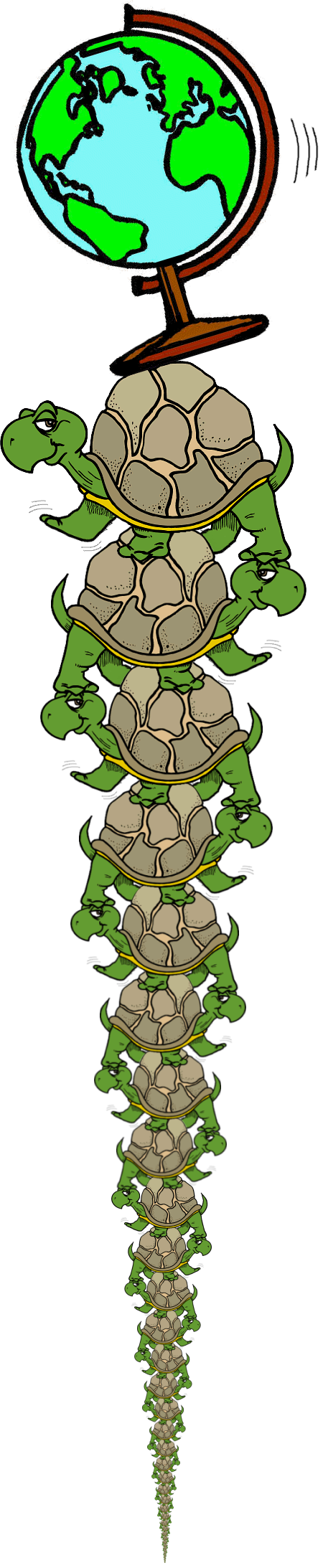

We’re told we live in the Enlightenment, that Reason™ sits on the throne and superstition has been banished to the attic. Yet when I disguised a little survey as “metamodern,” almost none came out as fully Enlightened. Three managed to shed every trace of the premodern ghost, one Dutch wanderer bypassed Modernity entirely, and not a single soul emerged free of postmodern suspicion. So much for humanity’s great rational awakening. Perhaps Modernity wasn’t a phase we passed through at all, but a mirage we still genuflect before, a lifestyle brand draped over a naked emperor.

The Enlightenment as Marketing Campaign

The Enlightenment is sold to us as civilisation’s great coming-of-age: the dawn when the fog of superstition lifted and Reason took the throne. Kant framed it as “man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity” – an Enlightenment bumper sticker that academics still like to polish and reapply. But Kant wasn’t writing for peasants hauling mud or women without the vote; he was writing for his own coterie of powdered-wig mandarins, men convinced their own habits of rational debate were humanity’s new universal destiny.

Modernity, in this story, isn’t a historical stage we all inhabited. It’s an advertising campaign: Reason™ as lifestyle brand, equality as tagline, “progress” as the logo on the tote bag. Modernity, in the textbooks, is billed as a historical epoch, a kind of secular Pentecost in which the lights came on and we all finally started thinking for ourselves. In practice, it was more of a boutique fantasy, a handful of gentlemen mistaking their own rarefied intellectual posture for humanity’s destiny.

The Archetype That Nobody Lives In

At the core of the Enlightenment lies the archetype of Man™: rational, autonomous, unencumbered by superstition, guided by evidence, weighing pros and cons with the detachment of a celestial accountant. Economics repackaged him as homo economicus, forever optimising his utility function as if he were a spreadsheet in breeches.

But like all archetypes, this figure is a mirage. Our survey data, even when baited as a “metamodern survey”, never produced a “pure” Enlightenment subject.

- 3 scored 0% Premodern (managing, perhaps, to kick the gods and ghosts to the kerb).

- 1 scored 0% Modern (the Dutch outlier: 17% Premodern, 0% Modern, 83% Post, skipping the Enlightenment altogether, apparently by bike).

- 0 scored 0% Postmodern. Every single participant carried at least some residue of suspicion, irony, or relativism.

The averages themselves were telling: roughly 18% Premodern, 45% Modern, 37% Postmodern. That’s not an age of Reason. That’s a muddle, a cocktail of priestly deference, rationalist daydreams, and ironic doubt.

Even the Greats Needed Their Crutches

If the masses never lived as Enlightenment subjects, what about the luminaries? Did they achieve the ideal? Hardly.

- Descartes, desperate to secure the cogito, called in God as guarantor, dragging medieval metaphysics back on stage.

- Kant built a cathedral of reason only to leave its foundations propped up by noumena: an unseeable, unknowable beyond.

- Nietzsche, supposed undertaker of gods, smuggled in his own metaphysics of will to power and eternal recurrence.

- William James, surveying the wreckage, declared that “truth” is simply “what works”, a sort of intellectual aspirin for the Enlightenment headache.

And economists, in a fit of professional humiliation, pared the rational subject down to a corpse on life support. Homo economicus became a creature who — at the very least, surely — wouldn’t choose to make himself worse off. But behavioural economics proved even that meagre hope to be a fantasy. People burn their wages on scratch tickets, sign up for exploitative loans, and vote themselves into oblivion because a meme told them to.

If even the “best specimens” never fully embodied the rational archetype, expecting Joe Everyman, who statistically struggles to parse a sixth-grade text and hasn’t cracked a book since puberty, to suddenly blossom into a mini-Kant is wishful thinking of the highest order.

The Dual Inertia

The real story isn’t progress through epochs; it’s the simultaneous drag of two kinds of inertia:

- Premodern inertia: we still cling to sacred myths, national totems, and moral certainties.

- Modern inertia: we still pretend the rational subject exists, because democracy, capitalism, and bureaucracy require him to.

The result isn’t a new epoch. It’s a cultural chimaera: half-superstitious, half-rationalist, shot through with irony. A mess, not a phase..

Arrow’s Mathematical Guillotine

Even if the Enlightenment dream of a rational demos were real, Kenneth Arrow proved it was doomed. His Impossibility Theorem shows that no voting system can turn individual rational preferences into a coherent “general will.” In other words, even a parliament of perfect Kants would deadlock when voting on dinner. The rational utopia is mathematically impossible.

So when we are told that democracy channels Reason, we should hear it as a polite modern incantation, no sturdier than a priest blessing crops.

Equality and the Emperor’s Wardrobe

The refrain comes like a hymn: “All men are created equal.” But the history is less inspiring. “Men” once meant property-owning Europeans; later it was generously expanded to mean all adult citizens who’d managed to stay alive until eighteen. Pass that biological milestone, and voilà — you are now certified Rational, qualified to determine the fate of nations.

And when you dare to question this threadbare arrangement, the chorus rises: “If you don’t like democracy, capitalism, or private property, just leave.” As if you could step outside the world like a theatre where the play displeases you. Heidegger’s Geworfenheit makes the joke bitter: we are thrown into this world without choice, and then instructed to exit if we find the wallpaper distasteful. Leave? To where, precisely? The void? Mars?

The Pre-Modern lord said: Obey, or be exiled. The Modern democrat says: Vote, or leave. And the Post-Enlightenment sceptic mutters: Leave? To where, exactly? Gravity? History? The species? There is no “outside” to exit into. The system is not a hotel; it’s the weather.

Here the ghost of Baudrillard hovers in the wings, pointing out that we are no longer defending Reason, but the simulacrum of Reason. The Emperor’s New Clothes parable once mocked cowardice: everyone saw the nudity but stayed silent. Our situation is worse. We don’t even see that the Emperor is naked. We genuinely believe in the fineries, the Democracy™, the Rational Man™, the sacred textile of Progress. And those who point out the obvious are ridiculed: How dare you mock such fineries, you cad!

Conclusion: The Comfort of a Ghost

So here we are, defending the ghost of a phase we never truly lived. We cling to Modernity as if it were a sturdy foundation, when in truth it was always an archetype – a phantom rational subject, a Platonic ideal projected onto a species of apes with smartphones. We mistook it for bedrock, built our institutions upon it, and now expend colossal energy propping up the papier-mâché ruins. The unfit defend it out of faith in their own “voice,” the elites defend it to preserve their privilege, and the rest of us muddle along pragmatically, dosing ourselves with Jamesian aspirin and pretending it’s progress.

Metamodernism, with its marketed oscillation between sincerity and irony, is less a “new stage” than a glossy rebranding of the same old admixture: a bit of myth, a bit of reason, a dash of scepticism. And pragmatism –James’s weary “truth is what works” – is the hangover cure that keeps us muddling through.

Modernity promised emancipation from immaturity. What we got was a new set of chains: reason as dogma, democracy as ritual, capitalism as destiny. And when we protest, the system replies with its favourite Enlightenment lullaby: If you don’t like it, just leave.

But you can’t leave. You were thrown here. What we call “Enlightenment” is not a stage in history but a zombie-simulation of an ideal that never drew breath. And yet, like villagers in Andersen’s tale, we not only guard the Emperor’s empty wardrobe – we see the garments as real. The Enlightenment subject is not naked. He is spectral, and we are the ones haunting him.