I’ll bite. This notion is in the news again, dredged up with the Epstein Files™, as though moral panic were a renewable resource.

NB: This is the post that inspired me to write the essay on voting age restrictions.

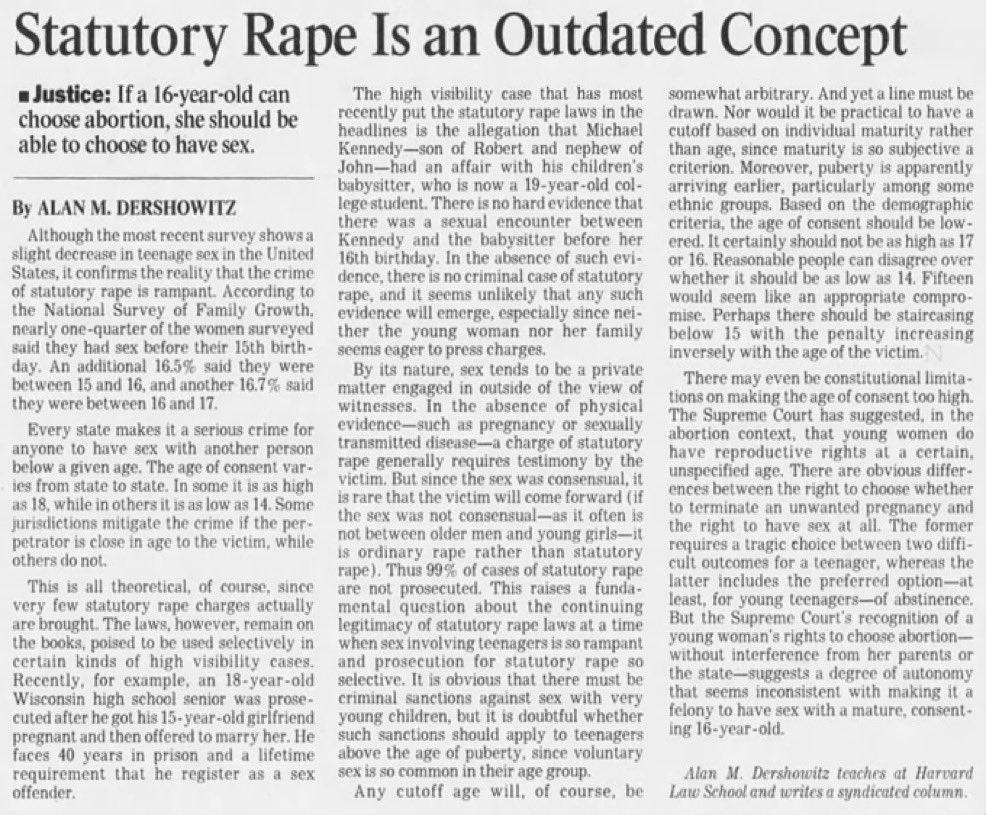

if a 16-year-old can choose abortion,

then she should be able to choose to have sex

In the newspaper clipping above, legal scholar Alan Dershowitz argues that if a 16-year-old can choose abortion, then she should be able to choose to have sex. The argument is presented as sober, rational, and juridical. A syllogism offered as disinfectant.

There are many philosophical problems with the equivalence. I am not interested in most of them.

I’ve written before that age as a proxy for maturity collapses immediately into a Sorites paradox. It assumes commensurability where none exists. It treats human development as discretised and legible, when it is anything but. The law must draw lines. Philosophy does not have that luxury. But that is not why this argument resurfaces now.

What interests me is the moral contamination reflex it reliably provokes. The rule is tacit but rigid: if you reason calmly about a taboo subject, you must be defending it. If you defend it, you must desire it. If you desire it, you must be guilty of it. Logic becomes circumstantial evidence.

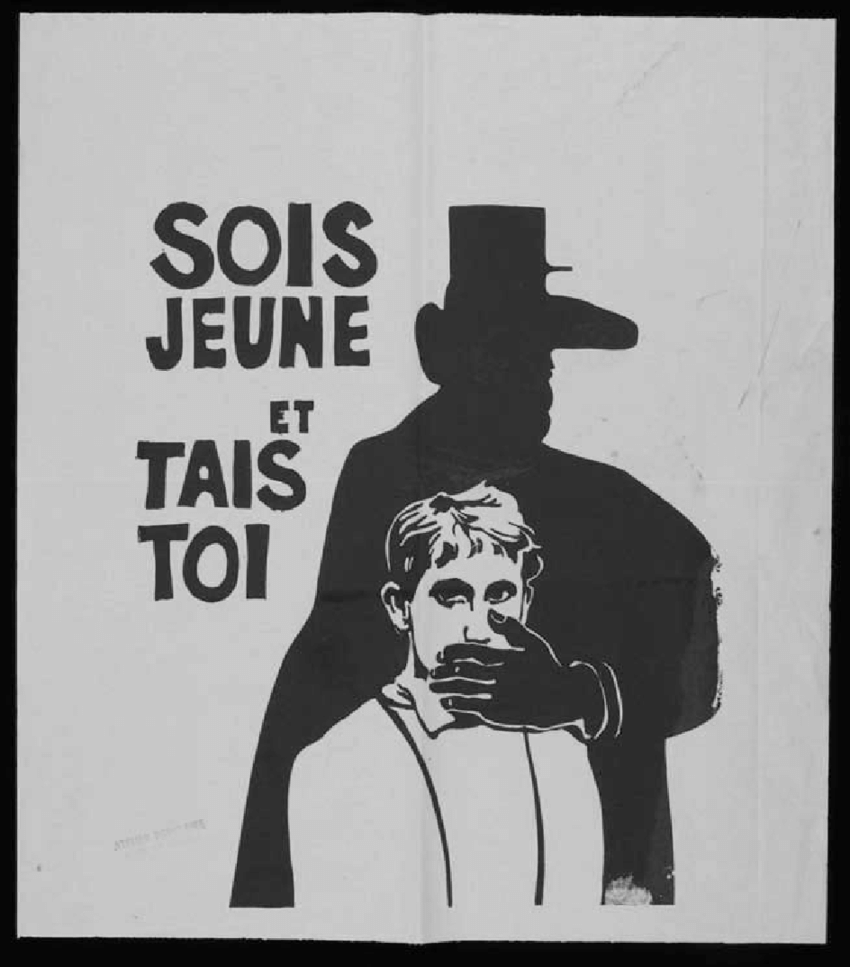

This reflex is not new. Nor is it confined to contemporary Anglo-American culture. Half a century ago, it played out publicly in France, with consequences that are now being retrospectively moralised into caricature.

In January and May of 1977, a petition published in Le Monde floated the abrogation of what was then called the “sexual majority”. In January of the same year, a separate petition called for the release of three men accused of having sex with boys and girls between the ages of twelve and fifteen. Among the signatories were Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, and Gilles Deleuze.

Today, this episode is typically invoked as a moral mic drop. No argument is examined. No context is interrogated. No distinction is drawn between legal reasoning, political provocation, and moral endorsement. The conclusion is immediate and terminal: these figures were monsters, or fools, or both.

The logic is familiar by now. If they signed, they must have approved. If they approved, they must have desired. If they desired, they must have practised. Analysis collapses into accusation.

None of this requires defending the petitions, the arguments, or the acts in question. It requires only defending a principle that has apparently become intolerable: that an argument can be examined without imputing motive, desire, or personal conduct to the person making it.

This is where liberal societies reveal a particular hypocrisy. They claim to value reasoned debate, yet routinely launder moral intuitions through rationalist language, then react with fury when someone exposes the laundering process. Legal thresholds are treated as if they were moral truths rather than negotiated compromises shaped by fear, harm minimisation, optics, and historical contingency.

Once the compromise hardens into law, the line becomes sacred. To question it is not civic scrutiny but moral trespass. To analyse it is to signal deviance. This is why figures like Foucault are not criticised for being wrong, but for having asked the question at all. The question itself becomes the crime.

It is often said, defensively, that emotion precedes logic. True enough. But this is usually offered as an excuse rather than a diagnosis. The supposed human distinction is not that we feel first, but that we can reflect on what we feel, examine it, and sometimes resist it. The historical record suggests we do this far less than we like to believe.

The real taboo here is not sex, or age, or consent. It is the suggestion that moral reasoning might survive contact with uncomfortable cases. That one might analyse the coherence of a law without endorsing the behaviour it regulates. That one might describe a moral panic without siding with its villains.

Instead, we have adopted a simpler rule: certain questions may not be asked without self-implication. This preserves moral theatre. It also guarantees that our laws remain philosophically incoherent while everyone congratulates themselves for having the correct instincts.

Logic, in this arrangement, is not a virtue. It is a liability. And history suggests that anyone who insists on using it will eventually be posthumously condemned for doing so.