I’ve written a lot on the insufficiency of language, and it’s not even an original idea. Language, our primary tool for sharing thoughts and ideas, harbours a fundamental flaw: it’s inherently insufficient for conveying precise meaning. While this observation isn’t novel, recent developments in artificial intelligence provide us with new ways to illuminate and examine this limitation. Through a progression from simple geometry to complex abstractions, we can explore how language both serves and fails us in different contexts.

The Simple Made Complex

Consider what appears to be a straightforward instruction: Draw a 1-millimetre square in the centre of an A4 sheet of paper using an HB pencil and a ruler. Despite the mathematical precision of these specifications, two people following these exact instructions would likely produce different results. The variables are numerous: ruler calibration, pencil sharpness, line thickness, paper texture, applied pressure, interpretation of “centre,” and even ambient conditions affecting the paper.

This example reveals a paradox: the more precisely we attempt to specify requirements, the more variables we introduce, creating additional points of potential divergence. Even in mathematics and formal logic—languages specifically designed to eliminate ambiguity—we cannot escape this fundamental problem.

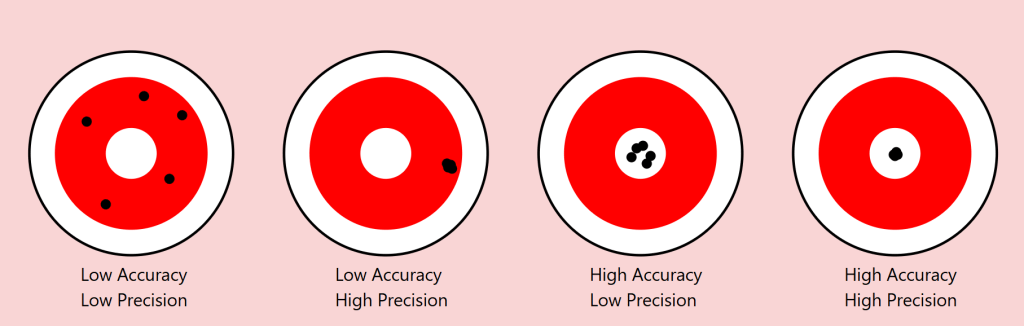

Precision vs Accuracy: A Useful Lens

The scientific distinction between precision and accuracy provides a valuable framework for understanding these limitations. In measurement, precision refers to the consistency of results (how close repeated measurements are to each other), while accuracy describes how close these measurements are to the true value.

Returning to our square example:

- Precision: Two people might consistently reproduce their own squares with exact dimensions

- Accuracy: Yet neither might capture the “true” square we intended to convey

As we move from geometric shapes to natural objects, this distinction becomes even more revealing. Consider a maple tree in autumn. We might precisely convey certain categorical aspects (“maple,” “autumn colours”), but accurately describing the exact arrangement of branches and leaves becomes increasingly difficult.

The Target of Meaning: Precision vs. Accuracy in Communication

To understand language’s limitations, we can borrow an illuminating concept from the world of measurement: the distinction between precision and accuracy. Imagine a target with a bullseye, where the bullseye represents perfect communication of meaning. Just as archers might hit different parts of a target, our attempts at communication can vary in both precision and accuracy.

Consider four scenarios:

- Low Precision, Low Accuracy

When describing our autumn maple tree, we might say “it’s a big tree with colourful leaves.” This description is neither precise (it could apply to many trees) nor accurate (it misses the specific characteristics that make our maple unique). The communication scatters widely and misses the mark entirely. - High Precision, Low Accuracy

We might describe the tree as “a 47-foot tall maple with exactly 23,487 leaves displaying RGB color values of #FF4500.” This description is precisely specific but entirely misses the meaningful essence of the tree we’re trying to describe. Like arrows clustering tightly in the wrong spot, we’re consistently missing the point. - Low Precision, High Accuracy

“It’s sort of spreading out, you know, with those typical maple leaves turning reddish-orange, kind of graceful looking.” While imprecise, this description might actually capture something true about the tree’s essence. The arrows scatter, but their centre mass hits the target. - High Precision, High Accuracy

This ideal state is rarely achievable in complex communication. Even in our simple geometric example of drawing a 1mm square, achieving both precise specifications and accurate execution proves challenging. With natural objects and abstract concepts, this challenge compounds exponentially.

The Communication Paradox

This framework reveals a crucial paradox in language: often, our attempts to increase precision (by adding more specific details) can actually decrease accuracy (by moving us further from the essential meaning we’re trying to convey). Consider legal documents: their high precision often comes at the cost of accurately conveying meaning to most readers.

Implications for AI Communication

This precision-accuracy framework helps explain why AI systems like our Midjourney experiment show asymptotic behaviour. The system might achieve high precision (consistently generating similar images based on descriptions) while struggling with accuracy (matching the original intended image), or vice versa. The gap between human intention and machine interpretation often manifests as a trade-off between these two qualities.

Our challenge, both in human-to-human and human-to-AI communication, isn’t to achieve perfect precision and accuracy—a likely impossible goal—but to find the optimal balance for each context. Sometimes, like in poetry, low precision might better serve accurate meaning. In other contexts, like technical specifications, high precision becomes crucial despite potential sacrifices in broader accuracy.

The Power and Limits of Distinction

This leads us to a crucial insight from Ferdinand de Saussure’s semiotics about the relationship between signifier (the word) and signified (the concept or object). Language proves remarkably effective when its primary task is distinction among a limited set. In a garden containing three trees—a pine, a maple, and a willow—asking someone to “point to the pine” will likely succeed. The shared understanding of these categorical distinctions allows for reliable communication.

However, this effectiveness dramatically diminishes when we move from distinction to description. In a forest of a thousand pines, describing one specific tree becomes nearly impossible. Each additional descriptive detail (“the tall one with a bent branch pointing east”) paradoxically makes precise identification both more specific and less likely to succeed.

An AI Experiment in Description

To explore this phenomenon systematically, I conducted an experiment using Midjourney 6.1, a state-of-the-art image generation AI. The methodology was simple:

- Generate an initial image

- Describe the generated image in words

- Use that description to generate a new image

- Repeat the process multiple times

- Attempt to refine the description to close the gap

- Continue iterations

The results support an asymptotic hypothesis: while subsequent iterations might approach the original image, they never fully converge. This isn’t merely a limitation of the AI system but rather a demonstration of language’s fundamental insufficiency.

A cute woman and her dog stand next to a tree

One can already analyse this for improvements, but let’s parse it together.

a cute womanWith this, we know we are referencing a woman, a female of the human species. There are billions of women in the world. What does she look like? What colour, height, ethnicity, and phenotypical attributes does she embody?

We also know she’s cute – whatever that means to the sender and receiver of these instructions.

I used an indefinite article, a, so there is one cute woman. Is she alone, or is she one from a group?

It should be obvious that we could provide more adjectives (and perhaps adjectives) to better convey our subject. We’ll get there, but let’s move on.

andWe’ve got a conjunction here. Let’s see what it connects to.

her dogShe’s with a dog. In fact, it’s her dog. This possession may not be conveyable or differentiable from some arbitrary dog, but what type of dog is it? Is it large or small? What colour coat? Is it groomed? Is it on a leash? Let’s continue.

stand It seems that the verb stand refers to the woman, but is the dog also standing, or is she holding it? More words could qualify this statement better.

next to a treeA tree is referenced. Similar questions arise regarding this tree. At a minimum, there is one tree or some variety. She and her dog are next to it. Is she on the right or left of it?

We think we can refine our statements with precision and accuracy, but can we? Might we just settle for “close enough”?

Let’s see how AI interpreted this statement.

Let’s deconstruct the eight renders above. Compositionally, we can see that each image contains a woman, a dog, and a tree. Do any of these match what you had in mind? First, let’s see how Midjourney describes the first image.

In a bout of hypocrisy, Midjourney refused to /DESCRIBE the image it just generated.

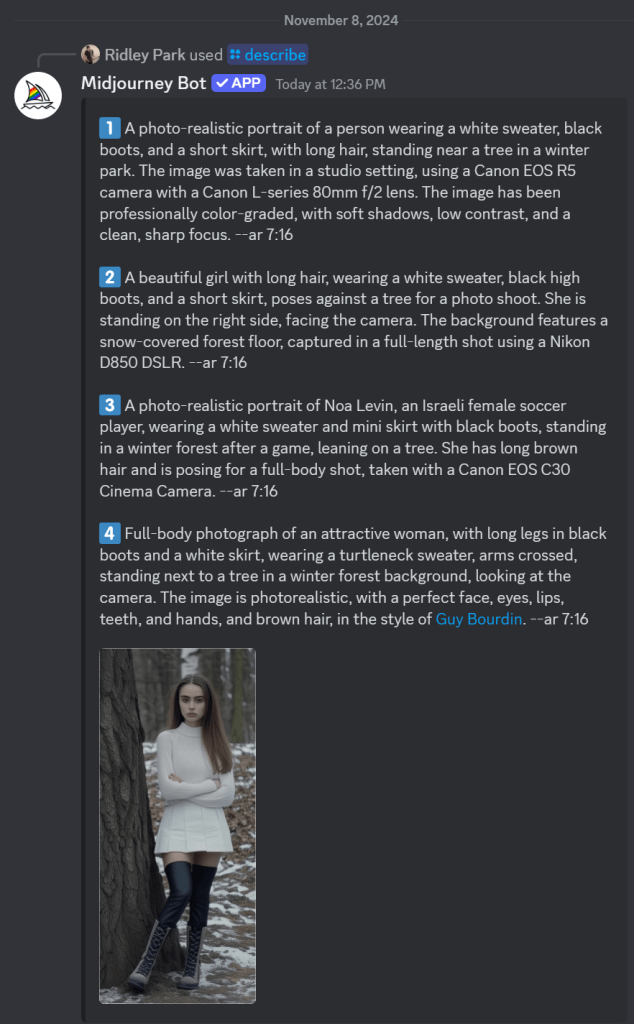

Last Midjourney description for now.

Let’s cycle through them in turn.

- A woman is standing to the left of an old-growth tree – twice identified as an oak tree. She’s wearing faded blue jeans and a loose light-coloured T-shirt. She’s got medium-length (maybe) red-brown hair in a small ponytail. A dog – her black and white dog identified as a pitbull, an American Foxhound, and an American Bulldog – is also standing on his hind legs. I won’t even discuss the implied intent projected on the animal – happy, playful, wants attention… In two of the descriptions, she’s said to be training it. They appear to be in a somewhat residential area given the automobiles in the background. We see descriptions of season, time of day, lighting, angle, quality,

- A woman is standing to the right of an old-growth tree. She’s wearing short summer attire. Her dog is perched on the tree.

- An older woman and her dog closer up.

- A read view of both a woman and her dog near an oak tree.

As it turned out, I wasn’t thrilled with any of these images, so I rendered a different one. Its description follows.

The consensus is that ‘a beautiful girl in a white dress and black boots stands next to a tree’ with a Jack Russell Terrier dog. I see birch trees and snow. It’s overcast. Let’s spend some time trying to reproduce it. To start, I’m consolidating the above descriptions. I notice some elements are missing, but we’ll add them as we try to triangulate to the original image.

A beautiful girl in a white dress and black boots stands next to a tree in a winter forest with birch trees. A Jack Russell Terrier dog is nearby, and the weather is cloudy. The photo has a cinematic style. --ar 128:71

This is pretty far off the mark. We need to account for the overall setting and composition, relative positioning, clothing, hair, camera, perspective – even lighting and film emulsion.

Let’s see how we can refine it with some adjectives. Before this, I asked Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 to describe the image. Perhaps we’ll get more details.

An atmospheric winter photograph was taken in what appears to be a birch and pine forest. The ground is partially covered with snow, creating a patchy pattern of white snow and brown leaves or soil. In the image, there's a person wearing winter attire consisting of a white knit turtleneck sweater, a white skirt, dark knee-high socks, and grey lace-up boots. They're standing against a large tree trunk with their arms crossed. Next to them is a Jack Russell Terrier mix dog with distinctive brown and white colouring. The dog appears to be well-behaved, sitting attentively beside the tree. The composition is quite striking, with the massive dark tree trunk serving as a central focal point against the misty, winter forest background. The white clothing of the person creates a visual echo with the white bark of birch trees visible in the background, as well as with the patches of snow on the ground. The overall mood of the photo is somewhat moody and contemplative, enhanced by what appears to be overcast lighting and the misty quality of the forest in the background. The colour palette is largely monochromatic, dominated by whites, greys, and browns, which adds to the winter atmosphere of the scene.

We don’t seem to be moving in a good direction. Let’s modify the initial prompt.

A beautiful girl in a white dress and tall laced black boots stands facing the camera to the right of large oak tree centred in the foreground of a winter forest with birch trees in the background. To the left of the tree is a Jack Russell Terrier dog looking at the camera, and the weather is cloudy. The photo has a cinematic style. --ar 128:71

I’ll allow the results to speak for themselves. Let’s see if we can’t get her out of the wedding gown and into a white jumper and skirt. I’ll bold the amends.

A beautiful girl in a white jumper and skirt wearing black leggings and tall laced black boots stands facing the camera to the right of large oak tree centred in the foreground of a winter forest with birch trees in the background. To the left of the tree is a Jack Russell Terrier dog looking at the camera, and the weather is cloudy. The photo has a cinematic style. --ar 128:71

s

A beautiful young woman with long brown hair pulled to the side of her face in a white jumper and white skirt wearing black leggings under tall laced black boots stands facing the camera to the right of large oak tree centred in the foreground of a winter forest with birch trees in the background. Patchy snow is on the ground. To the left of the tree is a Jack Russell Terrier dog looking at the camera, and the weather is overcast. The photo has a cinematic style. --ar 128:71What gives?

I think my point has been reinforced. I’m getting nowhere fast. Let’s give it one more go and see where we end up. I’ve not got a good feeling about this.

A single large oak tree centred in the foreground of a winter forest with birch trees in the background. Patches of snow is on the ground. To the right of the oak tree stands a beautiful young woman with long brown hair pulled to the side of her face in a white jumper and white skirt wearing black boots over tall laced black boots. She stands facing the camera. To the left of the tree is a Jack Russell Terrier dog looking at the camera, and the weather is overcast. The photo has a cinematic style. --ar 128:71

With this last one, I re-uploaded the original render along with this text prompt. Notice that the girl now looks the same and the scene (mostly) appears to be in the same location, but there are still challenges.

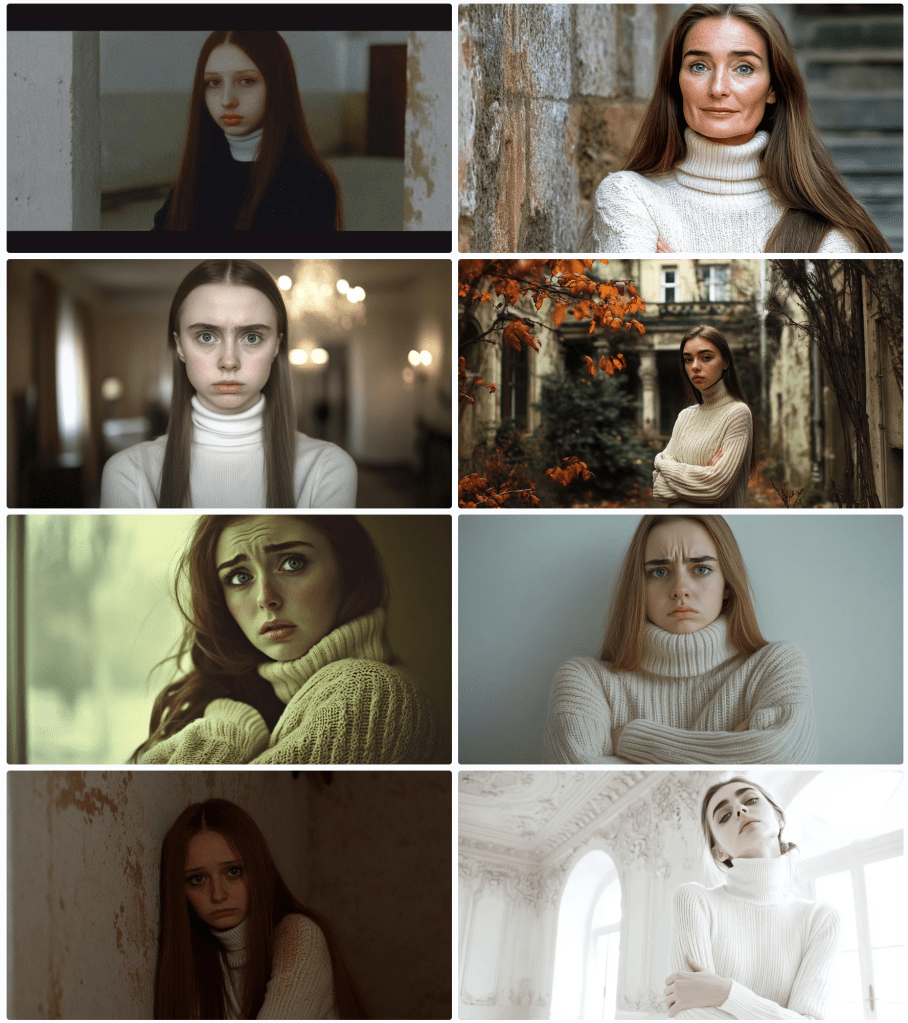

After several more divergent attempts, I decided to focus on one element – the girl.

As I regard the image, I’m thinking of a police sketch artist. They get sort of close, don’t they? They’re experts. I’m not confident that I even have the vocabulary to convey accurately what I see. How do I describe her jumper? Is that a turtleneck or a high collar? It appears to be knit. Is is wool or some blend? does that matter for an image? Does this pleated skirt have a particular name or shade of white? It looks as though she’s wearing black leggings – perhaps polyester. And those boots – how to describe them. I’m rerunning just the image above through a describe function to see if I can get any closer.

These descriptions are particularly interesting and telling. First, I’ll point out that AI attempts to identify the subject. I couldn’t find Noa Levin by a Google search, so I’m not sure how prominent she might be if she even exists at all in this capacity. More interesting still, the AI has placed her in a scenario where the pose was taken after a match. Evidently, this image reflects the style of photographer Guy Bourdin. Perhaps the jumper mystery is solved. It identified a turtleneck. I’ll ignore the tree and see if I can capture her with an amalgamation of these descriptions. Let’s see where this goes.

A photo-realistic portrait of Israeli female soccer player Noa Levin wearing a white turtleneck sweater, arms crossed, black boots, and a short skirt, with long brown hair, standing near a tree in a winter park. The image captured a full-length shot taken in a studio setting, using a Canon EOS R5 camera with a Canon L-series 80mm f/2 lens. The image has been professionally color-graded, with soft shadows, low contrast, and a clean, sharp focus. --ar 9:16

Close-ish. Let’s zoom in to get better descriptions of various elements starting with her face and hair.

Now, she’s a sad and angry Russian woman with (very) pale skin; large, sad, grey eyes; long, straight brown hair. Filmed in the style of either David LaChapelle or Alini Aenami (apparently misspelt from Alena Aenami). One thinks it was a SnapChat post. I was focusing on her face and hair, but it notices her wearing a white (oversized yet form-fitting) jumper sweater and crossed arms .

I’ll drop the angry bit – and then the sad.

Stick a fork in it. I’m done. Perhaps it’s not that language is insufficient; it that my language skills are insufficient. If you can get closer to the original image, please forward the image, the prompt, and the seed, so I can post it.

The Complexity Gradient

A clear pattern emerges when we examine how language performs across different levels of complexity:

- Categorical Distinction (High Success)

- Identifying shapes among limited options

- Distinguishing between tree species

- Basic color categorization

- Simple Description (Moderate Success)

- Basic geometric specifications

- General object characteristics

- Broad emotional states

- Complex Description (Low Success)

- Specific natural objects

- Precise emotional experiences

- Unique instances within categories

- Abstract Concepts (Lowest Success)

- Philosophical ideas

- Personal experiences

- Qualia

As we move up this complexity gradient, the gap between intended meaning and received understanding widens exponentially.

The Tolerance Problem

Understanding these limitations leads us to a practical question: what level of communicative tolerance is acceptable for different contexts? Just as engineering embraces acceptable tolerances rather than seeking perfect measurements, perhaps effective communication requires:

- Acknowledging the gap between intended and received meaning

- Establishing context-appropriate tolerance levels

- Developing better frameworks for managing these tolerances

- Recognizing when precision matters more than accuracy (or vice versa)

Implications for Human-AI Communication

These insights have particular relevance as we develop more sophisticated AI systems. The limitations we’ve explored suggest that:

- Some communication problems might be fundamental rather than technical

- AI systems may face similar boundaries as human communication

- The gap between intended and received meaning might be unbridgeable

- Future development should focus on managing rather than eliminating these limitations

Conclusion

Perhaps this is a simple exercise in mental masturbation. Language’s insufficiency isn’t a flaw to be fixed but a fundamental characteristic to be understood and accommodated. By definition, it can’t be fixed. The gap between intended and received meaning may be unbridgeable, but acknowledging this limitation is the first step toward more effective communication. As we continue to develop AI systems and push the boundaries of human-machine interaction, this understanding becomes increasingly critical.

Rather than seeking perfect precision in language, we might instead focus on:

- Developing new forms of multimodal communication

- Creating better frameworks for establishing shared context

- Accepting and accounting for interpretative variance

- Building systems that can operate effectively within these constraints

Understanding language’s limitations doesn’t diminish its value; rather, it helps us use it more effectively by working within its natural constraints.