I neither champion nor condemn tradition—whether it’s marriage, family, or whatever dusty relic society is currently parading around like a prize marrow at a village fête.

In a candid group conversation recently, I met “Jenny”, who declared she would have enjoyed her childhood much more had her father not “ruined everything” simply by existing. “Marie” countered that it was her mother who had been the wrecker-in-chief. Then “Lulu” breezed in, claiming, “We had a perfect family — we practically raised ourselves.”

“We had a perfect family; we practically raised ourselves.”

Now, here’s where it gets delicious:

Each of these women, bright-eyed defenders of “traditional marriage” and “traditional family” (cue the brass band), had themselves ticked every box on the Modern Chaos Bingo Card: children out of wedlock? Check. Divorces? Check. Performative, cold-marriage pantomimes? Absolutely—and scene.

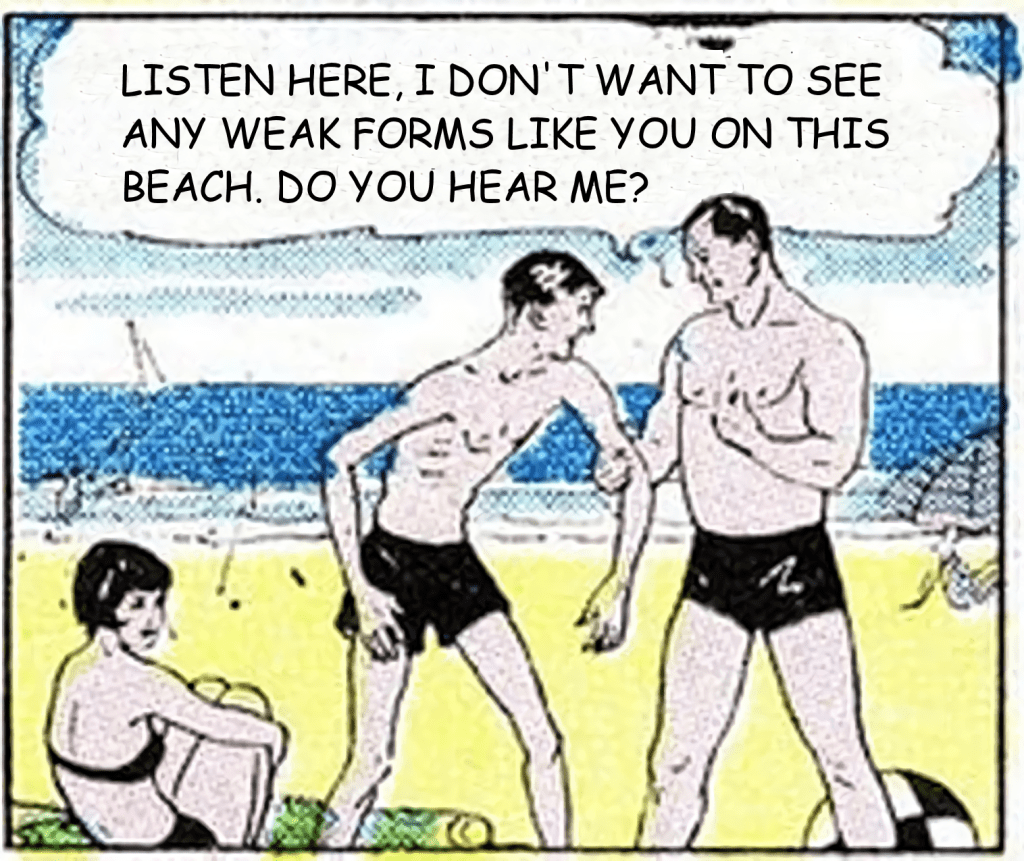

Their definition of “traditional marriage” is the vintage model: one cis-male, one cis-female, Dad brings home the bacon, Mum weeps quietly into the washing-up. Standard.

Let’s meet the players properly:

Jenny sprang from a union of two serial divorcées, each dragging along the tattered remnants of previous families. She was herself a “love child,” born out of wedlock and “forcing” another reluctant stroll down the aisle. Her father? A man of singular achievements: he paid the bills and terrorised the household. Jenny now pays a therapist to untangle the psychological wreckage.

Marie, the second of two daughters, was the product of a more textbook “traditional family”—if by textbook you mean a Victorian novel where everyone is miserable but keeps a stiff upper lip about it. Her mother didn’t want children but acquiesced to her husband’s demands (standard operating procedure at the time). Marie’s childhood was a kingdom where Daddy was a demigod and Mummy was the green-eyed witch guarding the gates of hell.

Lulu grew up in a household so “traditional” that it might have been painted by Hogarth: an underemployed, mostly useless father and a mother stretched thinner than the patience of a British Rail commuter. Despite—or because of—the chaos, Lulu claims it was “perfect,” presumably redefining the word in a way the Oxford English Dictionary would find hysterical. She, too, had a child out of wedlock, with the explicit goal of keeping feckless men at bay.

And yet—and yet—all three women cling, white-knuckled, to the fantasy of the “traditional family.” They did not achieve stability. Their families of origin were temples of dysfunction. But somehow, the “traditional family” remains the sacred cow, lovingly polished and paraded on Sundays.

Why?

Because what they’re chasing isn’t “tradition” at all — it’s stability, that glittering chimera. It’s nostalgia for a stability they never actually experienced. A mirage constructed from second-hand dreams, glossy 1950s propaganda, and whatever leftover fairy tales their therapists hadn’t yet charged them £150 an hour to dismantle.

Interestingly, none of them cared two figs about gay marriage, though opinions about gay parenting varied wildly—a kettle of fish I’ll leave splashing outside this piece.

Which brings us back to the central conundrum:

If lived experience tells you that “traditional family” equals trauma, neglect, and thinly-veiled loathing, why in the name of all that’s rational would you still yearn for it?

Societal pressure, perhaps. Local customs. Generational rot. The relentless cultural drumbeat that insists that marriage (preferably heterosexual and miserable) is the cornerstone of civilisation.

Still, it’s telling that Jenny and Marie were both advised by therapists to cut ties with their toxic families—yet in the same breath urged to create sturdy nuclear families for their own children. It was as if summoning a functional household from the smoking ruins of dysfunction were a simple matter of willpower and a properly ironed apron.

Meanwhile, Lulu—therapy-free and stubbornly independent—declares that raising oneself in a dysfunctional mess is not only survivable but positively idyllic. One can only assume her standards of “perfect” are charmingly flexible.

As the title suggests, this piece questions traditional families. I offer no solutions—only a raised eyebrow and a sharper question:

What is the appeal of clinging to a fantasy so thoroughly at odds with reality?

Your thoughts, dear reader? I’d love to hear your defences, your protests, or your own tales from the trenches.