The quickest way to derail any discussion of morality is to accuse someone of believing that ‘everything is relative’, so let’s start there. It’s a comforting accusation. It allows the accuser to stop thinking whilst feeling victorious. Unfortunately, it also misses the point almost entirely.

I am not claiming that everything is relative. I am claiming that ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are. More precisely, this particular binary pair does not track mind-independent properties of actions, but rather expresses subjective, relational, and power-inflected evaluations that arise within specific social contexts. That claim is not radical. It is merely inconvenient.

Good and Bad as Signals, Not Properties

When someone calls an action ‘bad’, they are not reporting a fact about the world in the way one might report temperature or velocity. They are signalling disapproval. Sometimes that disapproval is personal (subjective: ‘this sits badly with me’), sometimes social (relative: ‘people like us don’t do this’), and sometimes delegated (relative: ‘this violates the norms I’ve inherited and enforce’. The word does not describe. It acts.

The same applies to ‘good’. Approval, alignment, reassurance, permission. These terms function less like measurements and more like traffic signals. They coördinate behaviour. They reduce uncertainty. They warn, reward, and deter.

None of this requires moral scepticism, nihilism, or adolescent contrarianism. It requires only that we notice what the words are actually doing.

The Binary That Isn’t

Defenders of moral realism often retreat to a spectrum when pressed. Very well, they say, perhaps good and bad are not binary, but scalar. Degrees of goodness. Shades of wrongness. A neutral zone somewhere in the middle.

This is an improvement only in the most cosmetic sense. A single axis still assumes commensurability: that diverse considerations can be weighed on one ruler. Intuitively, this fails almost immediately. Good in what sense? Harm reduction? Loyalty? Legality? Survival? Compassion? Social order?

These dimensions do not line up. They cross-cut. They conflict. Which brings us to the example that refuses to die, for good reason.

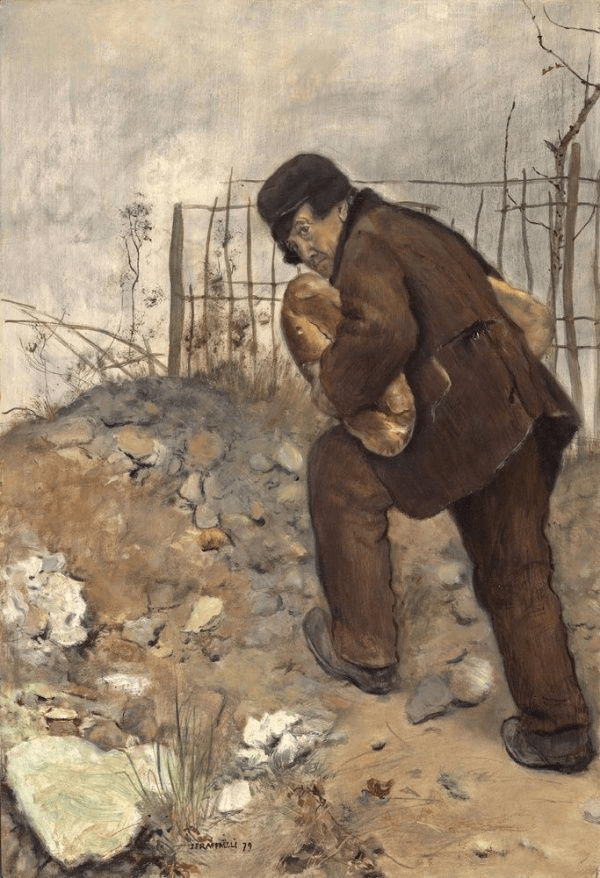

Stealing Bread

“I don’t mind stealing bread

From the mouths of decadence

But I can’t feed on the powerless

When my cup’s already overfilled”

— Hunger Strike, Temple of the Dog

Consider the theft of bread by a starving person. The act is simultaneously:

- bad relative to property norms

- good relative to survival

- bad relative to legal order

- good relative to care or compassion

- and neutral relative to anyone not implicated at all,

even if they were to form an opinion through exposure

There is no contradiction here. The act is multi-valent. What collapses this plurality into a single verdict is not moral discovery but authority. Law, religion, and institutional power do not resolve moral complexity. They override it.

What about ‘Mercy’?

When the law says, ‘Given the circumstances, you are free to go’, what it is not saying is: this act was not wrong. What it is saying is closer to:

We are exercising discretion this time.

Do not mistake that for permission.

The rule still stands.

The warning survives the mercy.

That’s why even leniency functions as discipline. You leave not cleansed, but marked. Grateful, cautious, newly calibrated. The system hasn’t revised its judgment; it has merely suspended its teeth for the moment. The shadow of punishment remains, doing quiet work in advance.

This is how power maintains itself without constant enforcement. Punishment teaches. Mercy trains.

You’re released, but you’ve learned the real lesson: the act is still classified as bad from the only perspective that ultimately matters. The next time, mitigation may not be forthcoming. The next time, the collapse will be final. So yes. Even when you ‘win’, the moral arithmetic hasn’t changed. Only the immediate invoice was waived.

Which is why legality is never a reliable guide to goodness, and acquittal is never absolution. It’s conditional tolerance, extended by an authority that never stopped believing it was right.

Power as the Collapse Mechanism

When the law says, ‘There may have been mitigating circumstances, but the act was wrong and must be punished’, it is not uncovering a deeper truth. It is announcing which perspective counts.

Mitigation is a courtesy, not a concession. Complexity is acknowledged, then flattened. The final judgment is scalar because enforcement demands it. A decision must be made. A sanction must follow. The plural is reduced to the singular by necessity, not insight.

Once this happens, the direction of explanation reverses. Punishment becomes evidence of wrongness rather than evidence of power. The verdict acquires moral weight retroactively.

From Ethics to Enforcement

At the local level, ‘good’ and ‘bad’ function as ethical shorthand. They help maintain relationships, minimise friction, and manage expectations. This is not morality in any grand sense. It is coordination under conditions of attachment and risk.

Problems arise when these local prescriptions harden into universal claims. When they are codified into rules, backed by sanctions, and insulated from challenge. At that point, the costs become real. Not morally real, but materially real. Fines. Exclusion. Imprisonment. Reputational death. Nothing metaphysical has changed. Only the consequences.

The God Upgrade

Religion intensifies this process by anchoring evaluative judgments to the structure of reality itself. What was once ‘bad here, among us’ becomes ‘bad everywhere, always’ is no longer a difference in perspective but a rebellion against the order of being. This is not ethical refinement. It is power laundering through eternity.

Not Everything Is Relative

To be clear, this is not an argument that facts do not exist, or that all distinctions dissolve into mush. It is an argument that ‘good’ and ‘bad’ do not behave like factual predicates, and that pretending otherwise obscures how judgments are actually made and enforced.

What is not relative is the existence of power, the reality of sanctions, or the psychological mechanisms through which norms are internalised and reproduced. What is relative is the evaluative overlay we mistake for moral truth once power has done its work.

Why This Is Ignored

None of this is new. It has been said, in various forms, for centuries. It is ignored because it offers no programme, no optimisation strategy, no moral high ground. It explains without redeeming. It clarifies without consoling.

And because it is difficult to govern people who understand that moral certainty usually arrives after authority, not before.