We are governed by phantoms. Not the fun kind that rattle chains in castles, but Enlightenment rational ghosts – imaginary citizens who were supposed to be dispassionate, consistent, and perfectly informed. They never lived, but they still haunt our constitutions and television pundits. Every time some talking head declares “the people have spoken”, what they really mean is that the ghosts are back on stage.

👉 Full essay: Rational Ghosts: Why Enlightenment Democracy Was Built to Fail

The conceit was simple: build politics as if it were an engineering problem. Set the rules right, and stability follows. The trouble is that the material – actual people – wasn’t blueprint-friendly. Madison admitted faction was “sown in the nature of man”, Rousseau agonised over the “general will”, and Condorcet managed to trip over his own math. They saw the cracks even while laying the foundation. Then they shrugged and built anyway.

The rational ghosts were tidy. Real humans are not. Our brains run on shortcuts: motivated reasoning, availability cascades, confirmation bias, Dunning–Kruger. We don’t deliberate; we improvise excuses. Education doesn’t fix it – it just arms us with better rationalisations. Media doesn’t fix it either – it corrals our biases into profitable outrage. The Enlightenment drafted for angels; what it got was apes with smartphones.

Even if the ghosts had shown up, the math betrayed them. Arrow proved that no voting system can translate preferences without distortion. McKelvey showed that whoever controls the sequence of votes controls the outcome. The “will of the people” is less an oracle than a Ouija board, and you can always see whose hand is pushing the planchette.

Scale finishes the job. Dunbar gave us 150 people as the human limit of meaningful community. Beyond that, trust decays into myth. Benedict Anderson called nations “imagined communities”, but social media has shattered the illusion. The national conversation is now a million algorithmic Dunbars, each convinced they alone are the real people.

Why did democracy limp along for two centuries if it was this haunted? Because it was on life-support. Growth, war, and civic myth covered the cracks. External enemies, national rituals, and propaganda made dysfunction look like consensus. It wasn’t design; it was borrowed capital. That capital has run out.

Cue the panic. The defences roll in: Churchill said democracy was the “least bad” system (he didn’t, but whatever). Voters self-correct. Education will fix it. It’s only an American problem. And if you don’t like it, what – authoritarianism? These are less arguments than incantations, muttered to keep the ghosts from noticing the creaks in the floorboards.

The real task isn’t to chant louder. It’s to stop pretending ghosts exist. Try subsidiarity: smaller-scale politics humans can actually grasp. Try deliberation: citizens’ assemblies show ordinary people can think, when not reduced to a soundbite. Try sortition: if elections are distorted by design, maybe roll the dice instead. Try polycentric governance: let overlapping authorities handle mismatch instead of hammering “one will”. None of these are perfect. They’re just less haunted.

Enlightenment democracy was built to fail because it was built for rational ghosts. The ghosts never lived. The floorboards are creaking. The task is ours: build institutions for the living, before the house collapses under its own myths.

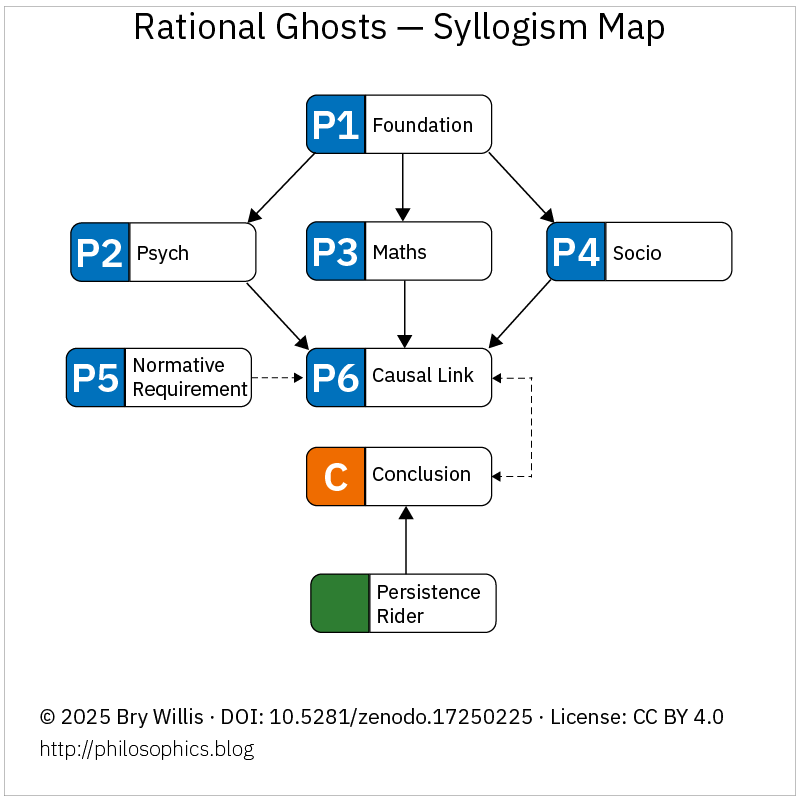

The Argument in Skeleton Form

Beneath the prose, the critique of Enlightenment democracy can be expressed as a syllogism:

a foundation that assumed rational citizens collides with psychological bias, mathematical impossibility, and sociological limits.

The outcome is a double failure – corrupted inputs and incoherent outputs – masked only by temporary props.

Yes, I agree with abandoning the pretense of “rational ghosts” and exploring political forms better suited to human reality! Subsidiarity (small, comprehensible communities), deliberation (citizen assemblies), random selection, and polycentric governance may be imperfect, but they are more realistic, less “haunted by illusions.”

But Enlightenment democracy is not doomed to failure: it will await the end of capitalism. We must not forget, in these times of climate violence, that Rousseau saw politics as a necessary asceticism. We will probably get there, but I fear it will be after the apocalypse (the bloody end of capitalism).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Capitalism operates like a faulty generator in a sealed room. The First Law tells us the energy (money) never disappears; it just sloshes around, converting public wealth into private heat. But the Second Law is the real kicker: every cycle leaves more of that energy wasted as friction –inequality, pollution, burnout – whilst the room (society and the biosphere) grows hotter and more chaotic. The system’s apologists call it ‘growth,’ but it’s just entropy in a suit. And when the generator sputters? The same folks who profited from the ‘light’ demand we all chip in to refuel it, even as the walls start to melt. It’s not a perpetual motion machine; it’s a countdown clock with a very expensive snooze button.

LikeLike

Entropy in costume was unmasked by Bernard Stiegler: he designates the current era not as the Capitalocene/Plantacione but as the “Entropocene.” This entropy of the system, a necessary “overflow,” has also been academically analyzed by Georges Bataille. Instead of donating capitalist accumulation, this same accumulation is invested in peripheral wars (formerly at the beginning of the Plantationocene, in slavery/colonization), regulated, which maintain the flow of capital to the top of the social pyramid.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. Thanks for this. Stiegler’s Entropocene captures precisely the terminal state of the system I described as “haunted.” The Enlightenment machine runs on deferred costs; entropy is simply its final accounting. Bataille saw this too: every surplus seeks an outlet, whether in colonial excess, military expenditure, or digital distraction. Capital’s waste stream is its sacrament.

In that sense, the “ghosts” I’ve been tracing are the residues of that entropic economy – costs we refuse to metabolize, deferred indefinitely into someone else’s future. The rational order was always a thermodynamic illusion: stability bought by exporting decay.

LikeLiked by 1 person