I have acquired a minor but persistent defect. When I try to type enough, my fingers often produce anough. Not always. Often enough to notice. Enough to be, regrettably, anough.

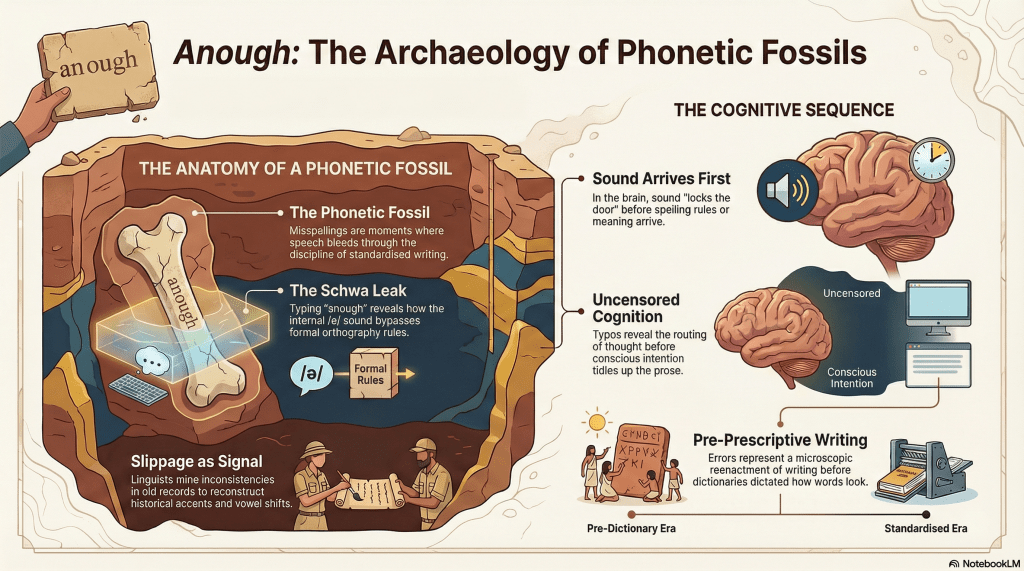

This is not a simple typo. The e and a keys are not conspirators with shared borders. This is not owned → pwned, where adjacency and gamer muscle memory do the heavy lifting. This is something more embarrassing and more interesting: a quasi-phonetic leak. A schwa forcing its way into print without permission. A clue for how I pronounce the word – like Depeche Mode’s I can’t get enough.

Internally, the word arrives as something like ənuf, /əˈnʌf/. English, however, offers no schwa key. So the system improvises. It grabs the nearest vowel that feels acoustically honest and hopes orthography won’t notice. Anough slips through. Language looks the other way.

Is this revelatory?

Not in the heroic sense. No breakthroughs, no flashing lights. But it is instructive in the way cracked pottery is instructive. You don’t learn anything new about ceramics, but you learn a great deal about how the thing was used.

This is exactly how historians and historical linguists treat misspellings in diaries, letters, and court records. They don’t dismiss them as noise. They mine them. Spelling errors are treated as phonetic fossils, moments where the discipline of standardisation faltered, and speech bled through. Before spelling became prescriptive, it was descriptive. People wrote how words sounded to them, not how an academy later insisted they ought to look.

That’s how vowel shifts are reconstructed. That’s how accents are approximated. That’s how entire sound systems are inferred from what appear, superficially, to be mistakes. The inconsistency is the data. The slippage is the signal.

Anough belongs to this lineage. It’s a microscopic reenactment of pre-standardised writing, occurring inside a modern, over-educated skull with autocorrect turned off. For a brief moment, sound outranks convention. Orthography lags. Then the editor arrives, appalled, to tidy things up.

What matters here is sequence. Meaning is not consulted first. Spelling rules are not consulted first. Sound gets there early, locks the door, and files the paperwork later. Conscious intention, as usual, shows up after the event and claims authorship. That’s why these slips are interesting and why polished language is often less so. Clean prose has already been censored. Typos haven’t. They show the routing. They reveal what cognition does before it pretends to be in charge.

None of this licenses forensic grandstanding. We cannot reconstruct personalities, intentions, or childhood trauma from rogue vowels. Anyone suggesting otherwise is repackaging graphology with better fonts. But as weak traces, as evidence that thought passes through sound before it passes through rules, they’re perfectly serviceable.

Language doesn’t just record history. It betrays it. Quietly. Repeatedly. In diaries, in marginalia, and occasionally, when you’re tired and trying to say you’ve had enough. Or anough.

I’ll spare you a rant on ghoti.