Philosophers adore two things: inventing problems and then fainting when someone solves them. For decades, we’ve been treated to the realism–idealism tug-of-war, that noble pantomime in which two exhausted metaphysical camps clutch the same conceptual teddy bear and insist the other stole it first. It’s almost touching.

Try out the MEOW GPT language parser.

Enter Nexal Ontology, my previous attempt at bailing water out of this sinking ship. It fought bravely, but as soon as anyone spotted even a faint resemblance to Whitehead, the poor thing collapsed under the weight of process-cosmology PTSD. One throwaway comment about ‘actual occasions’, and Nexal was done. Dead on arrival. A philosophical mayfly.

But MEOW* – The Mediated Encounter Ontology of the World – did not die. It shrugged off the Whitehead comparison with the indifference of a cat presented with a salad. MEOW survived the metaphysical death match because its commitments are simply too lean, too stripped-back, too structurally minimal for speculative cosmology to get its claws into. No prehensions. No eternal objects. No divine lure. Just encounter, mediation, constraint, and the quiet dignity of not pretending to describe the architecture of the universe.

And that’s why MEOW stands. It outlived Nexal not by being grander, but by being harder to kill.

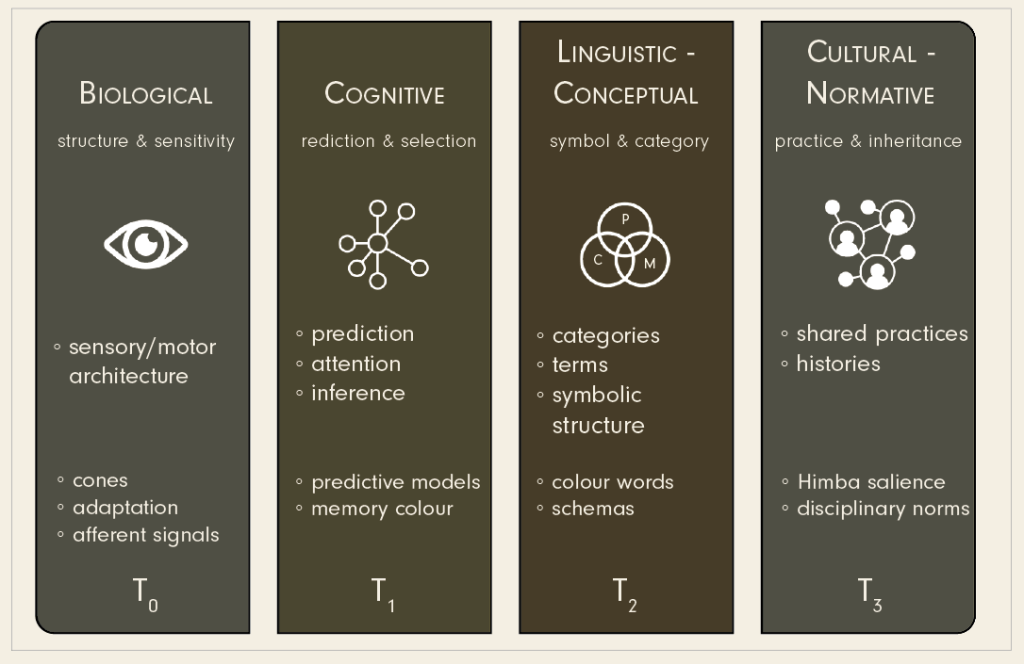

This little illustration gives the flavour:

• T0 Biological mediation – the body’s refusal to be neutral.

• T1 Cognitive mediation – the brain, doing predictive improv.

• T2 Linguistic–conceptual – words pretending they’re objective.

• T3 Cultural–normative – the inheritance of everyone else’s mistakes.

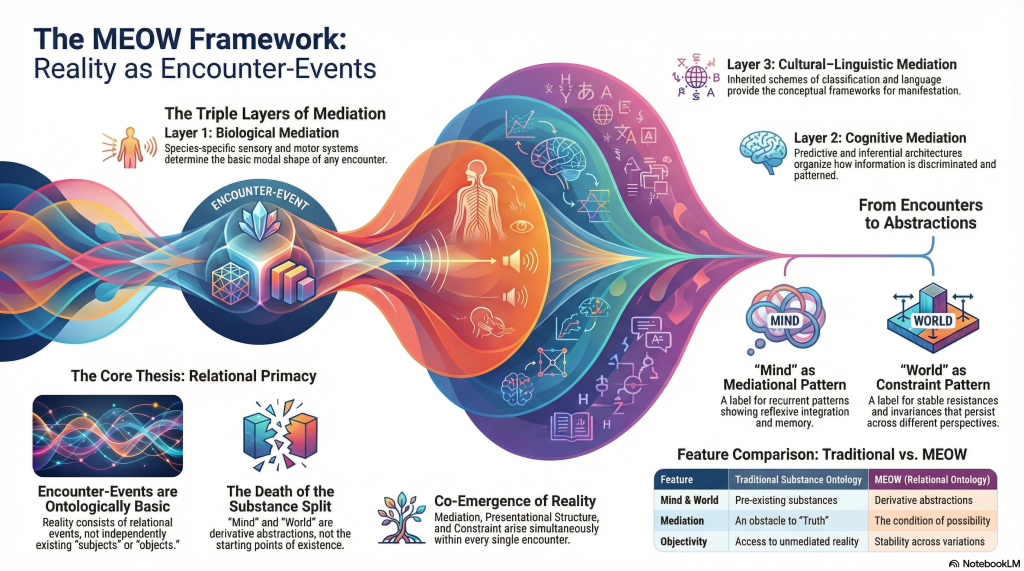

The essay argues that what we call ‘mind’ and ‘world’ are just abstractions we extract after the encounter, not the metaphysical scaffolding that produces it. Once you begin with the encounter-event itself – already mediated, already structured, already resistive – the mind–world binary looks about as sophisticated as a puppet show.

What the essay actually does

The Mediated Encounter Ontology of the World is the first framework I’ve written that genuinely sheds the Enlightenment scaffolding rather than rebuking it. MEOW shows:

- Mediation isn’t an epistemic flaw; it’s the only way reality appears.

- Constraint isn’t evidence of a noumenal backstage; it’s built into the encounter.

- Objectivity is just stability across mediation, not a mystical view-from-nowhere.

- ‘Mind’ and ‘world’ are names for recurring patterns, not metaphysical hotels.

- And – importantly – MEOW does all of this without drifting into Whiteheadian cosmological fan-fiction.

The full essay is now published and archived:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17685689

If you prefer a soft landing and the sound of a passable human voice explaining why metaphysics keeps tripping over its shoelaces, a NotebookLM discussion is here:

MEOW is the survivor because it does the one thing philosophy is terrible at: it refuses to pretend. No substances, no noumena, no grand metaphysical machinery—just a clean, relational architecture that mirrors how we actually encounter the world.

And frankly, that’s quite enough ontology for one lifetime.

* To be perfectly honest, I originally fled from Michela Massimi’s Perspectival Realism in search of a cleaner terminological habitat. I wanted to avoid the inevitable, dreary academic cross-pollination: the wretched fate of being forever shelved beside a project I have no quarrel with but absolutely no desire to be mistaken for. My proposed replacement, Nexal Ontology, looked promising until I realised it had wandered, by sheer lexical accident, into Whitehead’s garden – an unintentional trespass for which I refused to stick around to apologise. I could already hear the process-metaphysics crowd sharpening their teeth.

Early evasive action was required.

I preferred nexal to medial, but the terminology had already been colonised, and I am nothing if not territorial. Mediated Ontology would have staked its claim well enough, but something was missing – something active, lived, structural. Enter the Encounter.

And once the acronym MEO appeared on the page, I was undone. A philosopher is only human, and the gravitational pull toward MEOW was irresistible. What, then, could honour the W with appropriate pomp? The World, naturally. Thus was born The Mediated Encounter Ontology of the World.

Pretentious? Yes. Obnoxious? Also yes.

And so it remains—purring contentedly in its absurdity.