With the MEOW thesis now roaming freely across the intellectual savannah, knocking over conceptual furniture and frightening the rationalists, it’s time to walk through a simple example. We’ll stay safely within the realm of conscious perception for now. That way, no one panics, and everyone can pretend they’re on familiar ground.

Our case study: colour.

Or rather, the quite embarrassing misunderstanding of colour that Western philosophy has been peddling for roughly three centuries.

The Realist’s Apple: A Comedy of Certainty

Picture an apple on a table: plump, unashamedly spherical, wearing its redness like a badge of honour. The traditional Realist swears it’s red in itself, quite independent of anyone wandering in to admire it. The apple has redness the way it has mass, curvature, and that little bruise from the careless shop assistant. When you enter the room, you ‘see’ the red it’s been proudly radiating all along.

By school age, most of us are told that apples don’t ‘have’ colour; they merely reflect certain wavelengths. A minor complication. A mechanical detail. Nothing to disturb the fundamental metaphysical fantasy: that redness is still ‘out there’, waiting patiently for your eyes to come collect it.

It’s all very straightforward. Very tidy. And very wrong.

Idealists to the Rescue (Unfortunately)

Ask an Idealist about the apple and the entertainment begins.

The Berkeley devotee insists the apple exists only so long as it’s perceived – esse est percipi – which raises awkward questions about what happens when you step out for a cuppa. God, apparently, keeps the universe running as a kind of 24-hour perceptual babysitter. You may find this profound or you may find it disturbingly clingy.

The Kantian, inevitably wearing a waistcoat, insists the apple-in-itself is forever inaccessible behind the Phenomenal Veil of Mystery. What you experience is the apple-for-you, sculpted by space, time, causality, and a toolkit of categories you never asked for. This explains a lot about post-Kantian philosophy, not least the fixation on walls no one can climb.

Contemporary idealists get creative: proto-experience in everything, cosmic consciousness as universal substrate, matter as a sleepy epiphenomenon of Mind. It’s quite dazzling if you ignore the categories they’re smashing together.

What unites these camps is the conviction that mind is doing the heavy lifting and the world is an afterthought – inconvenient, unruly, and best kept in the margins.

The Shared Mistake: An Architectural Catastrophe

Both Realist and Idealist inherit the same faulty blueprint: mind here, world there – two self-contained realms entering into an epistemic handshake.

Realists cling to unmediated access (a fantasy incompatible with biology).

Idealists cling to sovereign mentality (a fantasy incompatible with objectivity).

Both take ‘experience’ to be a relation between two pre-existing domains rather than a single structured encounter.

This is the mistake. Not Realism’s claims about mind-independence. Not Idealism’s claims about mental primacy. The mistake is the architecture – the assumption of two separately-existing somethings that subsequently relate.

MEOW – yes, we’re calling it that – puts it bluntly:

The problem isn’t where colour is. The problem is assuming it has to be in something – mind or world – rather than in the event.

Redness isn’t inside your head or inside the apple.

It’s co-constituted by biological, cognitive, linguistic, and cultural mediation interacting with persistent constraint patterns.

Time to peel this onion… er, apple.

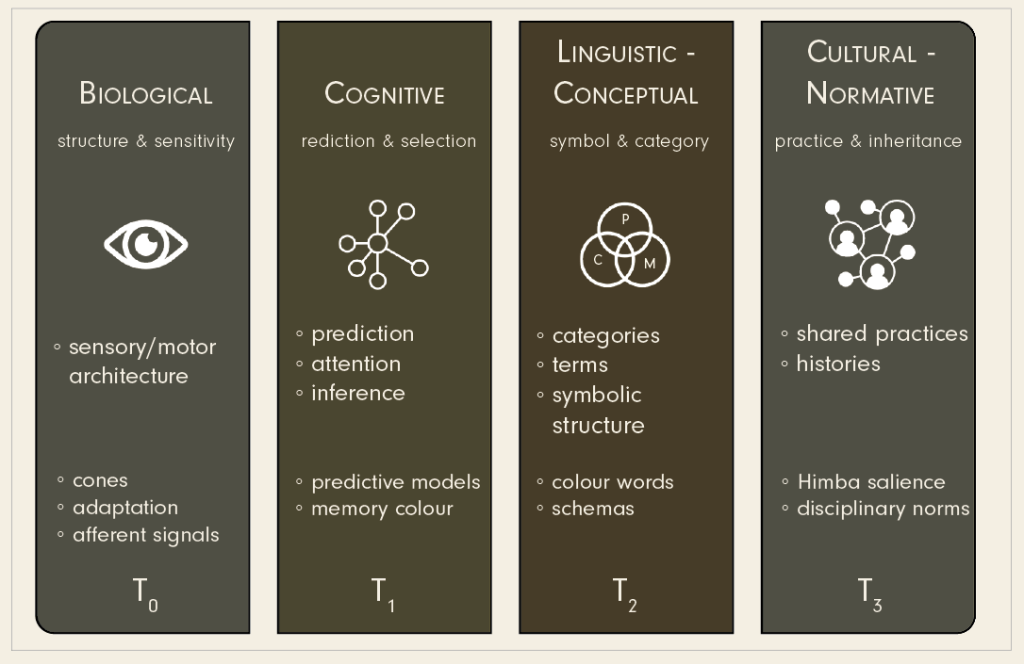

The Four Layers of Mediation (T₀–T₃)

A Ridiculously Oversimplified Cheat-Sheet That Still Outperforms Most Metaphysics Syllabi

T₀ – Biological Mediation

Structure and Sensitivity: the Architecture You Never Asked For

This is where the Enlightenment’s fantasy of ‘raw perception’ goes to die.

Your visual system transforms, filters, enhances, suppresses, and reconstructs before ‘red’ even reaches consciousness. Cone responses, opponent processes, retinal adaptation, spatial filtering – all of it happening before the poor cortex even gets a look-in.

You never perceive ‘wavelengths’. You perceive the output of a heavily processed biological pipeline.

The biology isn’t the barrier. The biology is the view.

T₁ – Cognitive Mediation

Prediction and Inference: You See What You Expect (Until Constraint Smacks You)

Your cognitive system doesn’t ‘receive’ colour information – it predicts it and updates the guess when necessary.

Memory colour biases perception toward canonical instances. Attentional gating determines what gets processed intensively and what gets summary treatment. Top-down modulation shapes what counts as signal versus noise.

There is no percept without mediation. There is no ‘raw data’ waiting underneath.

The Enlightenment liked to imagine perception as a passive window.

Cognition turns that window into a heavily editorialised newsfeed.

T₂ – Linguistic–Conceptual Mediation

Categories and Symbols: How Words Carve the Spectrum

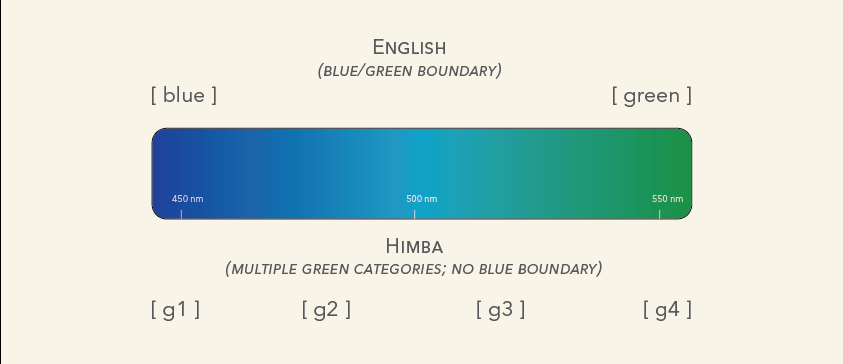

Enter the famous Whorf skirmishes.

Do words change perception?

Do they merely label pre-existing distinctions?

Do Russians really ‘see’ blue differently?

Berlin & Kay gave us focal colour universals – constraint patterns stable across cultures.

Roberson et al. gave us the Himba data – linguistic categories reshaping discrimination and salience.

The correct answer is neither universalism nor relativism. It’s MEOW’s favourite refrain:

Mediation varies; constraint persists.

Words don’t invent colours.

But they do reorganise the perceptual field, changing what pops and what hides.

T₃ – Cultural–Normative Mediation

Shared Practices: The Social Life of Perception

Your discipline, training, historical context, and shared norms tell you:

- which distinctions matter

- which differences ‘count’

- which patterns get ignored

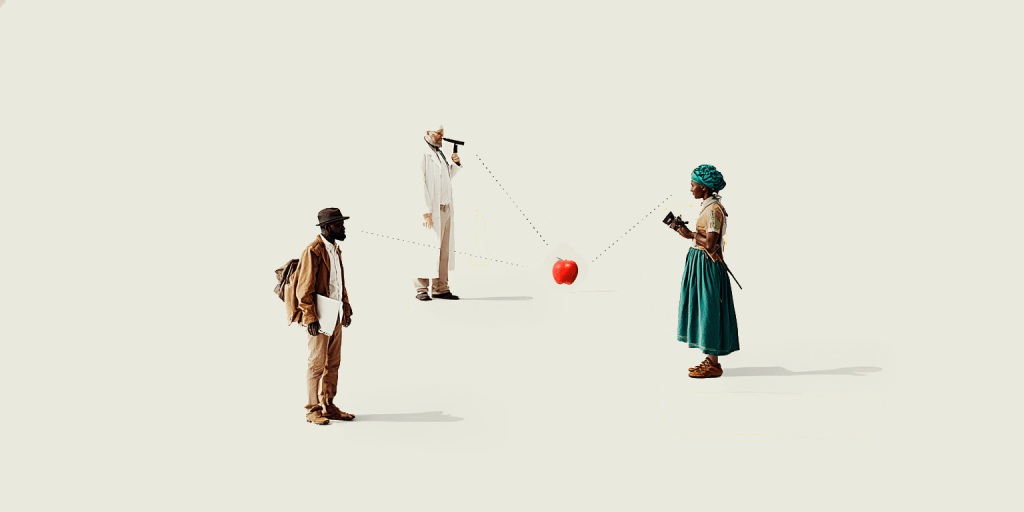

A Himba herder, a Renaissance painter, and a radiologist do not inhabit the same perceptual world – even when staring at the same patch of light.

Cultural mediation doesn’t rewrite biology; it reorganises priorities, salience, and interpretive readiness.

What Seeing Red Actually Involves (Step By Exhausting Step)

You walk into a room. Apple on table. Looks red. What just happened?

T₀ – Biological: Long wavelength light hits L-cones harder than M- and S-cones. Opponent channels compute (L−M). Adaptation shifts baseline. Edge detection fires. You don’t have ‘red’ yet – you have transformed photoreceptor output.

T₁ – Cognitive: Your brain predicts ‘apple, probably red’ based on shape and context. Memory colour pulls toward canonical apple-red. Attention allocates processing resources. Prediction matches input (roughly). System settles: ‘yes, red apple’.

T₂ – Linguistic–Conceptual: The continuous gradient gets binned: ‘red’, not ‘crimson’ or ‘scarlet’ unless you’re a designer. The category provides stability, ties this instance to others, makes it reportable.

T₃ – Cultural–Normative: Does the exact shade matter? Depends whether you’re buying it, photographing it, or painting it. Your practical context determines which distinctions you bother tracking.

And through all of this: Constraint. Metameric matches stay stable. Focal colours persist cross-culturally. Wavelength sensitivities don’t budge. The encounter isn’t arbitrary – but it’s not unmediated either.

What happened wasn’t: Mind Met World.

What happened was: an encounter-event unfolded, organised through four mediational layers, exhibiting stable constraint patterns that made it this and not that.

Where This Leaves Us

Colour is not ‘out there’. Colour is not ‘in here’.

Colour is the structured relational event of encounter.

Four mediation layers shape what appears.

Constraint patterns stabilise the encounter so we aren’t hallucinating wildly divergent rainbows.

There is no ‘apple as it really is’ waiting behind the encounter.

Nor is there a sovereign mind constructing its own private theatre.

There is only the event – where biological structure, cognitive dynamics, conceptual categories, and cultural histories co-emerge with the stable patterns of constraint we lazily call ‘the world’.

The apple was never red ‘in itself’.

You were never seeing it ‘as it really is’.

And the Enlightenment can finally take off its colour-blind uncle glasses and admit it’s been squinting at the wrong question for three hundred years.

Next time: Why visual illusions aren’t perception failing, but perception revealing itself.

Until then: stop asking where colour ‘really’ lives.

It lives in the event. And the event is mediated, constrained, and real enough.