Announcement: I’ll be taking a break from posting long-form articles for a while to focus on a project I’m developing. Instead, I’ll share progress summary updates.

Ontological Blindness in Modern Moral Science is a working title with a working subtitle as The Why Semantic Thickness, Measurement, and Reconciliation Go Wrong. No spoilers.

INSERT: I’ve only outlined and stubbed this Ontological blindness project, and I’ve already got another idea. I need to stop reading and engaging with the world.

I was listening to the Audible version of A.J. Ayer’s classic, Language, Truth, and Logic (1936)– not because I had time but because I listen to audiobooks when I work out. Ayer is a Logical Positivist, but I forgive him. He’s a victim of his time. In any case, I noticed several holes in his logic.

Sure, the book was published in 1936, and it is infamous for defending or creating Emotivism, a favourite philosophical whipping boy. I’m an Emotivist, so I disagree with the opposition. In fact, I feel their arguments are either strawmen or already defended by Ayer. I also agree with Ayer that confusing the map of language with the terrain of reality is a problem in philosophy (among other contexts), but it’s less excusable for a language philosopher.

In any case, I have begun a file to consider a new working title, Phenomenal Constraint and the Limits of Ontological Language. I might as well stay in the ontological space for a while. We’ll see where it leads, but first, I need to put the original project to bed.

Every time I commence a project, I create a thesis statement and an abstract to orient me. These may change over the course of a project, especially larger ones – more of an abstract than a thesis. This thesis has already changed a couple of times, but I feel it’s settled now.

Thesis Statement

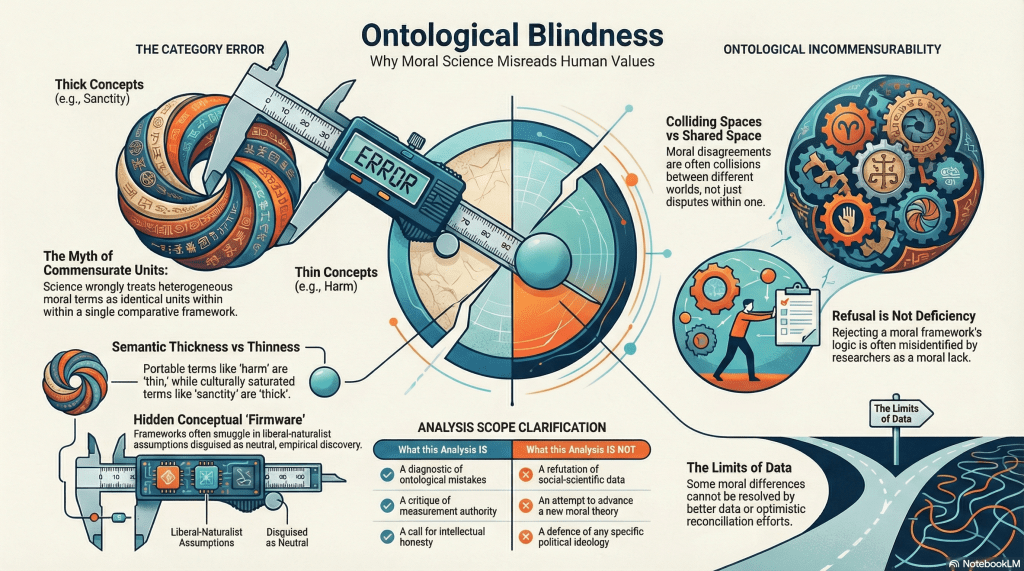

Modern moral psychology repeatedly commits a multi-layered category error by treating semantically and ontologically heterogeneous moral terms as commensurate units within a single comparative framework, while simultaneously treating parochial moral metaphysics as natural substrate.

This dual conflation—of semantic density with moral plurality, and of ontological commitment with empirical discovery—produces the false appearance that some moral systems are more comprehensive than others, when it in fact reflects an inability to register ontological incommensurability.

Moral Foundations Theory provides a clear and influential case of this broader mistake: a framework whose reconciliation-oriented conclusions depend not on empirical discovery alone, but on an unacknowledged liberal-naturalist sub-ontology functioning as conceptual ‘firmware’ mistaken for moral cognition itself.

Abstract

Modern moral psychology seeks to explain moral diversity through empirically tractable frameworks that assume cross-cultural comparability of moral concepts. This book argues that many such frameworks – including but not limited to Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) – rest on a persistent category error: the treatment of semantically and ontologically heterogeneous moral terms as commensurate units within a single evaluative space.

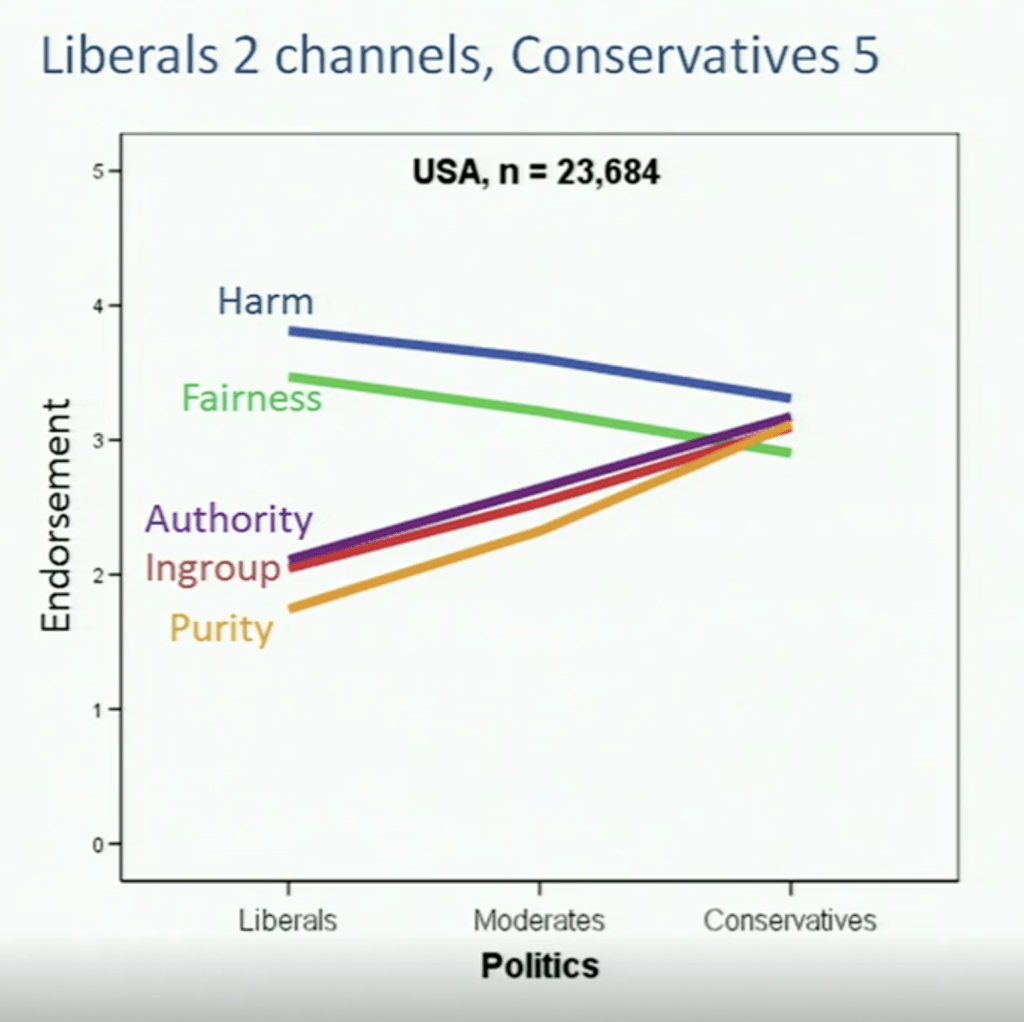

The argument proceeds in four stages. First, it establishes that moral vocabularies differ not merely in emphasis but in semantic thickness: some terms (e.g. harm, fairness) are comparatively thin, portable, and practice-independent, while others (e.g. loyalty, authority, sanctity) are culturally saturated, institution-dependent, and ontologically loaded. Treating these as equivalent ‘foundations’ mistakes density for plurality.

Second, the book shows that claims of moral ‘breadth’ or ‘completeness’ smuggle normativity into ostensibly descriptive research, crossing the Humean is/ought divide without acknowledgement. Third, it argues that this slippage is not accidental but functional, serving modern culture’s demand for optimistic, reconcilable accounts of moral disagreement.

Finally, through sustained analysis of MFT as a worked example, the book demonstrates how liberal naturalist individualism operates as an unacknowledged sub-ontology – conceptual firmware that determines what counts as moral, measurable, and comparable. The result is not moral pluralism, but ontological imperialism disguised as empirical neutrality.

The book concludes by arguing that acknowledging ontological incommensurability does not entail nihilism or relativistic indifference, but intellectual honesty about the limits of moral science and the false comfort of reconciliation narratives.

Ideation

I’ve been pondering ontologies a lot these past few weeks, especially how social ontologies undermine communication. More recently, I’ve been considering how sub-ontologies come into play. A key catalyst for my thinking has been Jonathan Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory, but I’ve also been influenced by George Lakoff, Kurt Gray, and Joshua Greene, as I’ve shared recently. I want to be clear: This book is not about politics or political science. It intends to about the philosophy of psychology and adjacent topics.

At the highest levels, I see fundamental category errors undermining MFT, but as I inspected, it goes deeper still, so much so that it’s too much to fit into an essay or even a monograph, so I will be targeting a book so I have room to expand and articulate my argumentation. Essays are constraining, and the narrative flow – so to speak – is interrupted by footnotes and tangents.

In a book, I can spend time framing and articulating – educating the reader without presuming an in-depth knowledge. This isn’t to say that this isn’t a deep topic, and I’ll try not to patronise readers, but this topic is not only counterintuitive, it is also largely unorthodox and may ruffle a few feathers.

I’m not sure how much I’ll be able to share, but I’d like to be transparent in the process and perhaps gather some inputs along the way.

Methodology

Sort of… I’ve used Scrivener in the past for organising and writing fiction. This is the first time I’ am organising nonfiction. We’ll see how it goes.