I’ve been working through the opening chapters of Octavia Butler’s Dawn. At one point, the alien Jdahya tells Lilith, “We watched you commit mass suicide.”*

The line unsettles not because of the apocalypse itself, but because of what it presumes: that “humanity” acted as one, as if billions of disparate lives could be collapsed into a single decision. A few pulled triggers, a few applauded, some resisted despite the odds, and most simply endured. From the alien vantage, nuance vanishes. A species is judged by its outcome, not by the uneven distribution of responsibility that produced it.

This is hardly foreign to us. Nationalism thrives on the same flattening. We won the war. We lost the match. A handful act; the many claim the glory or swallow the shame by association. Sartre takes it further with his “no excuses” dictum, even to do nothing is to choose. Howard Zinn’s “You can’t remain neutral on a moving train” makes the same move, cloaked in the borrowed authority of physics. Yet relativity undermines it: on the train, you are still; on the ground, you are moving. Whether neutrality is possible depends entirely on your frame of reference.

What all these formulations share is a kind of metaphysical inflation. “Agency” is treated as a universal essence, something evenly spread across the human condition. But in practice, it is anything but. Most people are not shaping history; they are being dragged along by it.

One might sketch the orientations toward the collective “apple cart” like this:

- Tippers with a vision: the revolutionaries, ideologues, or would-be prophets who claim to know how the cart should be overturned.

- Sycophants: clinging to the side, riding the momentum of others’ power, hoping for crumbs.

- Egoists: indifferent to the cart’s fate, focused on personal comfort, advantage, or escape.

- Stabilisers: most people, clinging to the cart as it wobbles, preferring continuity to upheaval.

- Survivors: those who endure, waiting out storms, not out of “agency” but necessity.

The Stabilisers and Survivors blur into the same crowd, the former still half-convinced their vote between arsenic and cyanide matters, the latter no longer believing the story at all. They resemble Seligman’s shocked dogs, conditioned to sit through pain because movement feels futile.

And so “humanity” never truly acts as one. Agency is uneven, fragile, and often absent. Yet whether in Sartre’s philosophy, Zinn’s slogans, or Jdahya’s extraterrestrial indictment, the temptation is always to collapse plurality into a single will; you chose this, all of you. It is neat, rhetorically satisfying, and yet wrong.

Perhaps Butler’s aliens, clinical in their judgment, are simply holding up a mirror to the fictions we already tell about ourselves.

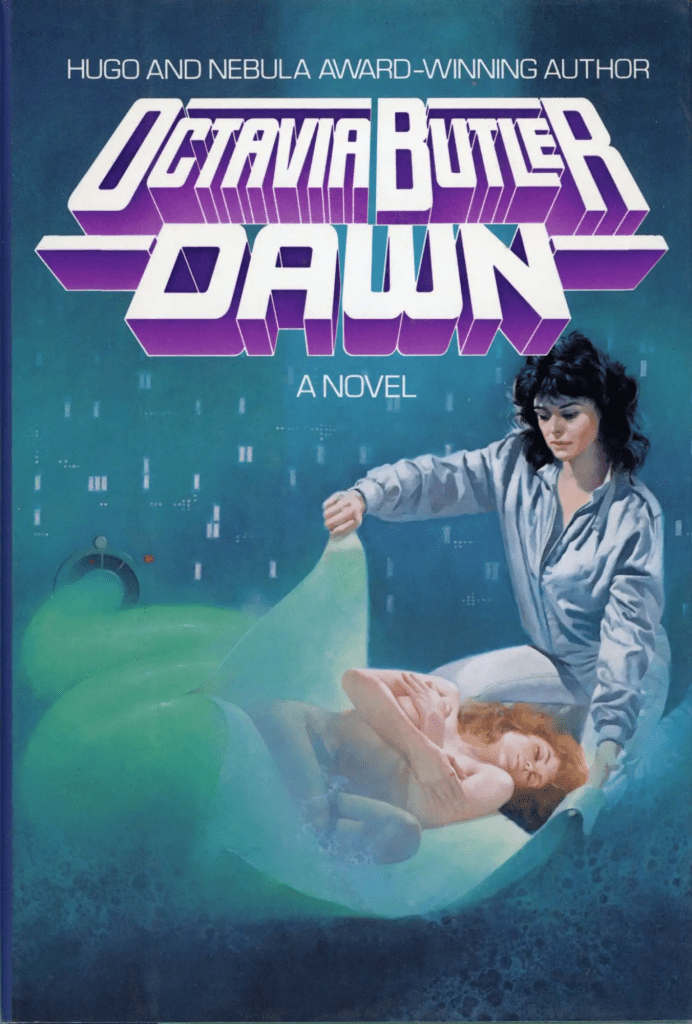

As an aside, this version of the book cover is risible. Not to devolve into identity politics, but Lilith is a dark-skinned woman, not a pale ginger. I can only assume that some target science fiction readers have a propensity to prefer white, sapphic adjacent characters.

I won’t even comment further on the faux 3D title treatment, relic of 1980s marketing.

* Spoiler Alert: As this statement about mass suicide is a Chapter 2 event, I am not inclined to consider it a spoiler. False alarm.