After this was published, 5 additional posts were made, diving deeper into the content.

- Constraint is not freedom — the piano plays itself.

- Continuity is not identity — you are sediment, not sovereignty.

- Manipulability disproves authorship — your will can be bent invisibly.

- Others misjudge you — through their own distortions.

- You cannot originate yourself — and thus cannot own your acts.

Why the cherished myth of human autonomy dissolves under the weight of our own biology

We cling to free will like a comfort blanket—the reassuring belief that our actions spring from deliberation, character, and autonomous choice. This narrative has powered everything from our justice systems to our sense of personal achievement. It feels good, even necessary, to believe we author our own stories.

But what if this cornerstone of human self-conception is merely a useful fiction? What if, with each advance in neuroscience, our cherished notion of autonomy becomes increasingly untenable?

I. The Myth of Autonomy: A Beautiful Delusion

Free will requires that we—some essential, decision-making “self”—stand somehow separate from the causal chains of biology and physics. But where exactly would this magical pocket of causation exist? And what evidence do we have for it?

Your preferences, values, and impulses emerge from a complex interplay of factors you never chose:

The genetic lottery determined your baseline neurochemistry and cognitive architecture before your first breath. You didn’t select your dopamine sensitivity, your amygdala reactivity, or your executive function capacity.

The hormonal symphony that controls your emotional responses operates largely beneath conscious awareness. These chemical messengers—testosterone, oxytocin, and cortisol—don’t ask permission before altering your perceptions and priorities.

Environmental exposures—from lead in your childhood drinking water to the specific traumas of your upbringing—have sculpted neural pathways you didn’t design and can’t easily rewire.

Developmental contingencies have shaped your moral reasoning, impulse control, and capacity for empathy through processes invisible to conscious inspection.

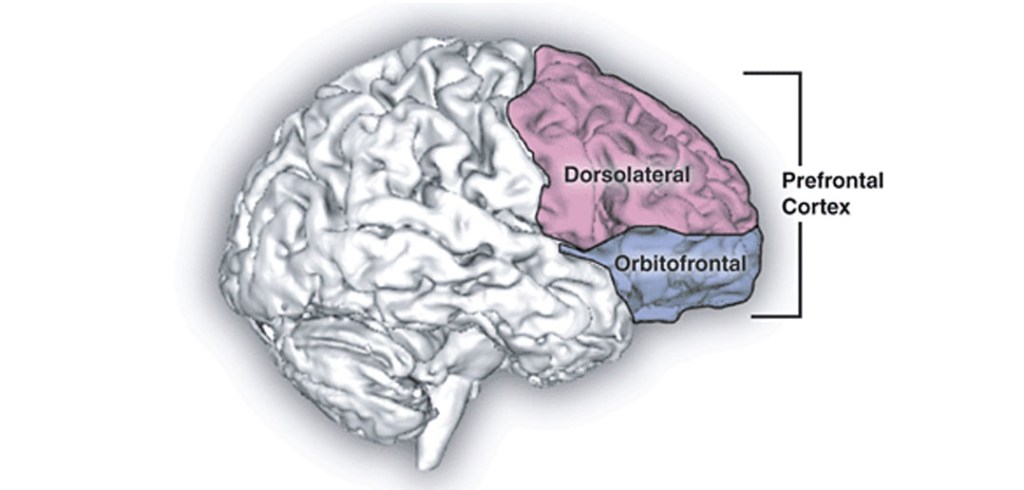

Your prized ability to weigh options, inhibit impulses, and make “rational” choices depends entirely on specific brain structures—particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)—operating within a neurochemical environment you inherited rather than created.

You occupy this biological machinery; you do not transcend it. Yet, society holds you responsible for its outputs as if you stood separate from these deterministic processes.

transcranial direct current stimulation over the DLPFC alters moral reasoning, especially regarding personal moral dilemmas. The subject experiences these externally induced judgments as entirely their own, with no sense that their moral compass has been hijacked

II. The DLPFC: Puppet Master of Moral Choice

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex serves as command central for what we proudly call executive function—our capacity to plan, inhibit, decide, and morally judge. We experience its operations as deliberation, as the weighing of options, as the essence of choice itself.

And yet this supposed seat of autonomy can be manipulated with disturbing ease.

When researchers apply transcranial magnetic stimulation to inhibit DLPFC function, test subjects make dramatically different moral judgments about identical scenarios. Under different stimulation protocols, the same person arrives at contradictory conclusions about right and wrong without any awareness of the external influence.

Similarly, transcranial direct current stimulation over the DLPFC alters moral reasoning, especially regarding personal moral dilemmas. The subject experiences these externally induced judgments as entirely their own, with no sense that their moral compass has been hijacked.

If our most cherished moral deliberations can be redirected through simple electromagnetic manipulation, what does this reveal about the nature of “choice”? If will can be so easily influenced, how free could it possibly be?

III. Hormonal Puppetmasters: The Will in Your Bloodstream

Your decision-making machinery doesn’t stop at neural architecture. Your hormonal profile actively shapes what you perceive as your autonomous choices.

Consider oxytocin, popularly known as the “love hormone.” Research demonstrates that elevated oxytocin levels enhance feelings of guilt and shame while reducing willingness to harm others. This isn’t a subtle effect—it’s a direct biological override of what you might otherwise “choose.”

Testosterone tells an equally compelling story. Administration of this hormone increases utilitarian moral judgments, particularly when such decisions involve aggression or social dominance. The subject doesn’t experience this as a foreign influence but as their own authentic reasoning.

These aren’t anomalies or edge cases. They represent the normal operation of the biological systems governing what we experience as choice. You aren’t choosing so much as regulating, responding, and rebalancing a biochemical economy you inherited rather than designed.

IV. The Accident of Will: Uncomfortable Conclusions

If the will can be manipulated through such straightforward biological interventions, was it ever truly “yours” to begin with?

Philosopher Galen Strawson’s causa sui argument becomes unavoidable here: To be morally responsible, one must be the cause of oneself, but no one creates their own neural and hormonal architecture. By extension, no one can be ultimately responsible for actions emerging from that architecture.

What we dignify as “will” may be nothing more than a fortunate (or unfortunate) biochemical accident—the particular configuration of neurons and neurochemicals you happened to inherit and develop.

This lens forces unsettling questions:

- How many behaviours we praise or condemn are merely phenotypic expressions masquerading as choices? How many acts of cruelty or compassion reflect neurochemistry rather than character?

- How many punishments and rewards are we assigning not to autonomous agents, but to biological processes operating beyond conscious control?

- And perhaps most disturbingly: If we could perfect the moral self through direct biological intervention—rewiring neural pathways or adjusting neurotransmitter levels to ensure “better” choices—should we?

- Or would such manipulation, however well-intentioned, represent the final acknowledgement that what we’ve called free will was never free at all?

A Compatibilist Rebuttal? Not So Fast.

Some philosophers argue for compatibilism, the view that determinism and free will can coexist if we redefine free will as “uncoerced action aligned with one’s desires.” But this semantic shuffle doesn’t rescue moral responsibility.

If your desires themselves are products of biology and environment—if even your capacity to evaluate those desires depends on inherited neural architecture—then “acting according to your desires” just pushes the problem back a step. You’re still not the ultimate author of those desires or your response to them.

What’s Left?

Perhaps we need not a defence of free will but a new framework for understanding human behaviour—one that acknowledges our biological embeddedness while preserving meaningful concepts of agency and responsibility without magical thinking.

The evidence doesn’t suggest we are without agency; it suggests our agency operates within biological constraints we’re only beginning to understand. The question isn’t whether biology influences choice—it’s whether anything else does.

For now, the neuroscientific evidence points in one direction: The will exists, but its freedom is the illusion.