I wouldn’t eat or sleep if I didn’t have to. Let’s talk about eating.

I eat to survive. Some people live to eat; I eat to live. I don’t like food, and I don’t like to eat. These sentiments may share something in common.

I think about my food preferences on a normal curve. Most dishes score a 5 (a T score of 50; just divide by 10 to lose the zero)—give or take. Quite a few are 4s and 6s. A few are 3s and 7s. Even fewer are 2s and 8s, which are virtually indistinguishable from 1s and 9s or 0s and 10s. Ninety-five per cent of all foods fall between 3 and 7; eighty-five per cent fall between 4 and 6, where six is barely OK. My personal favourites tap out at about 7.

On the low end, once I get to 3, it might as well be a zero. Perhaps if I were at risk of dying, I’d partake. On the high end, an 8, 9, or 10? I wouldn’t know. I’m not sure I’ve ever eaten better than an 8, and that was just once.

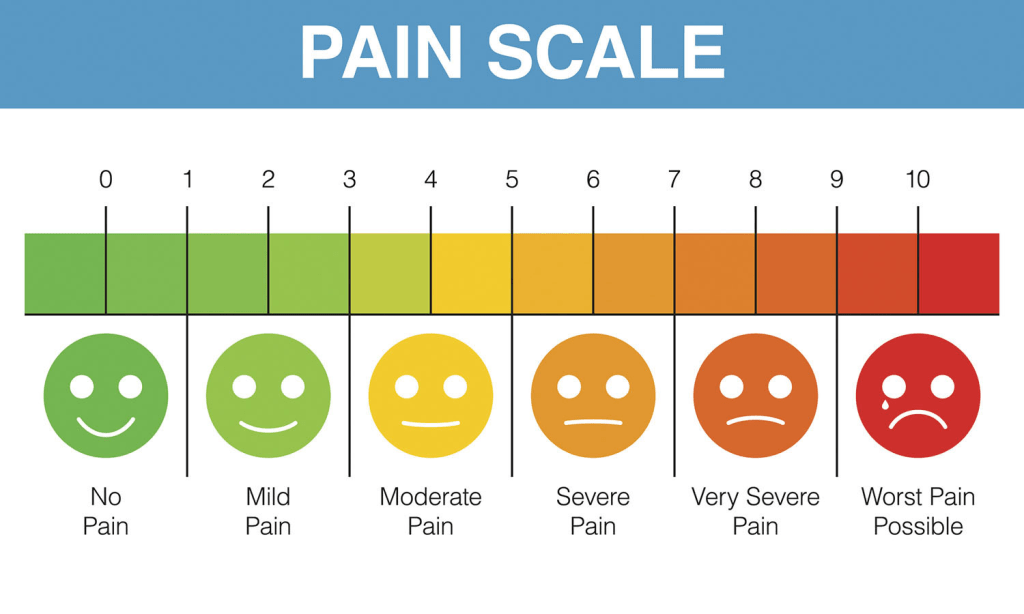

You might say my scale isn’t calibrated. Maybe. I think of the food scale as I do the pain scale but in reverse because 10 is worse. It’s difficult to frame the boundaries. Actually, the pain scale is easier.

I was hospitalized for months in 2023. It didn’t so much make me reassess my pain scale as to confirm it. Prior to this visit, on a scale of 0 to 10, I had never subjectively experienced pain above a 4, save for dental nerve pain. During this visit, I had pain approaching if not equaling dental pain—8s and 9s. The 9 might have been a 10, but I was leaving headroom to allow for something worse still.

An instructive story involves my wife delivering a pregnancy. She wanted to be wholly natural—no drugs. It only took one contraction to toss that idea aside. She realized that the pain she had registered was beyond her perceived boundaries. Perhaps food is like that for me. I’m not sure I’ll ever experience an analogous event to find out.

Since my typical intake is a 5, it’s not something I look forward to or enjoy. I have no interest in extending the experience. This leads us to mealtimes—another time sink. I dislike mealtime as much as eating. I’m a mindful introvert. I don’t mind people one-on-one, but I want to be mindful. If I’m eating, I want to be mindful of eating. If I am talking, I want to focus on that. I get no pleasure from mealtime banter.

I’ve once experienced a memorable meal, a meal that felt above all the rest. It was at a French restaurant in Beverly Hills. When I returned some months later, it had converted into a bistro with a different menu. The experience was not to be repeated. Besides, chasing happiness is a fool’s errand. I wouldn’t have likely had the same experience even if the second meal was identical to the first, given diminishing marginal returns on pleasure.

Does this mean I don’t like anything? No. It means I might like, say, some pizza more than a burger. For me, most meat is a 5 or below. Chicken might be a 6. Fish is a 3 at best. Chicken prepared a certain way might even break 7, but that’s pretty much the cap—except for that one time I’ve already mentioned.

Most people I’ve spoken with about this can’t imagine not loving food. When I lived in Chicago, with its foodie culture, they thought I was borderline insane. Does anyone else have a disinterested relationship with food? Let’s defer the sleep topic to another day.