I recently encountered a kindred soul on Mastodon – figuratively, metaphorically, and within the usual constraints of online encounter – and it prompted a familiar line of thought.

This is not the first time I’ve ‘met’ someone in this way. The pattern repeats often enough to be worth naming. We find common ground outside orthodoxy, experience that alignment as a relief, and linger there for a time. Then, usually without conflict or drama, we discover that the overlap is partial. Our ontological or metaphysical commitments diverge. The conversation thins. We drift apart, sometimes reconnecting later when that same shared ground is encountered again from another angle.

I’ve also had several people tell me they appreciate my work and would like to integrate it into their own projects. These invitations are genuine and generous. But they often come with an unspoken expectation that my arguments can be extended toward metaphysical positions I do not share: panpsychism, animism, various forms of consciousness-first cosmology, or other reconstructive moves of that kind.

The refusal, when it comes, is not personal. It isn’t even oppositional. I’m generally open to building, extending, or synthesising. I’m not interested in bridging toward foundations I regard as doing a different kind of work altogether.

What interests me is that this scenario seems common among heterodox thinkers, regardless of where they ultimately stop. We recognise one another in the refusal of orthodoxy, assume a deeper alignment, and then encounter a quiet limit. The question is not who is right, but why this keeps happening.

That is what this post is about. If you’re heterodox, this pattern might feel uncomfortably familiar.

You encounter someone whose work resonates immediately. They reject the same orthodoxies, bristle at the same institutional pieties, and seem unimpressed by the same explanatory shortcuts. There is a brief sense of relief. Recognition. A feeling of intellectual companionship that is rare enough to feel precious. And then, quietly, the connexion thins.

Nothing collapses. No argument detonates. No offence is given or taken. One of you simply steps somewhere the other cannot or will not follow. A metaphysical claim is introduced. A moral anchor is asserted. A spiritual horizon appears. Or just as often, it doesn’t. From that point on, the conversation continues, but the current has changed. The sense of shared footing is gone.

What’s unsettling is not disagreement as such. It’s the near-miss. The sense that alignment was real, but provisional. That something connected and then slipped, without anyone doing anything wrong.

Many heterodox thinkers experience this repeatedly and interpret it as a failure: of communication, generosity, openness, or perhaps courage. It isn’t. It’s structural.

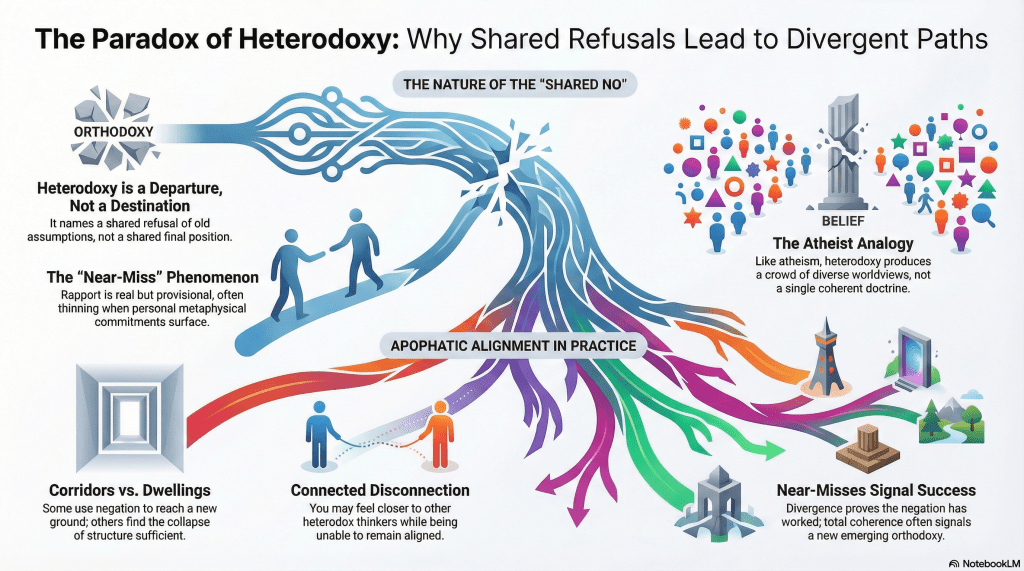

Heterodoxy Is a Departure, Not a Destination

The mistake is assuming heterodoxy names a shared position. It doesn’t. It names a shared refusal.

Heterodox thinkers do not leave orthodoxy in the same way or for the same reasons. They reject different assumptions, at different depths, under different pressures. The overlap happens because multiple escape routes pass through the same early terrain: scepticism about progress, discomfort with universalism, doubt about linguistic sufficiency, suspicion of institutional neutrality. The paths converge briefly. Then they diverge. What differs is not intelligence or seriousness, but where each thinker expects the process to terminate.

Some heterodoxies are transitional. They break the old frame in order to reach another one, however provisional, poetic, or mystical. Others are terminal. They break the frame to show that no final frame is forthcoming. The exposure of limits is the result. The connexion holds only as long as those expectations remain untested.

Apophatic Alignment

A useful way to understand this is apophatic. In apophatic traditions, alignment is achieved by negation. What matters is not what is affirmed, but what is refused. ‘Not this’ is the only stable common ground. Every positive claim risks rebuilding the very structure that was just dismantled.

Much heterodox thinking functions this way, whether it names itself as such or not. People gather around shared negations: not Enlightenment rationalism, not moral commensurability, not linguistic transparency, not institutional objectivity. There is relief in this shared stripping-away. A sense of clarity born of subtraction. The difficulty arises when negation is treated as incomplete.

Some experience the apophatic moment as a corridor, not a dwelling. They want a new ground, a new centre, a new synthesis. Consciousness, myth, the sacred, systems, emergence, vibes. Others experience the apophatic moment as sufficient. They stop where the structure collapses, without urgency to rebuild. Neither stance is an error. But they are not compatible for long.

The Atheist Problem

An analogy might help: Atheists often discover that atheism is the only thing they have in common. Remove belief in God, and what remains is not a worldview but a crowd. Libertarians, Marxists, humanists, nihilists, spiritual minimalists, scientistic optimists. The disappointment some feel is not a failure of atheism, but a misunderstanding of what a shared no can do. Heterodoxy works the same way.

Shared disbelief produces rapport. It does not produce coherence. Expecting it to is a category mistake inherited from the very universalising habits heterodoxy rejects.

Connected Disconnexion

This gives rise to a distinctive affect: connected disconnexion. You feel closer to other heterodox thinkers than to orthodox ones, yet you cannot remain aligned. You recognise their refusal, but not their resolution. Or their resolution, but not their refusal. The disconnection feels personal because the alignment felt rare. It isn’t personal. It’s ecological.

Heterodoxy does not form a community. It forms a pattern of overlapping partial alliances that dissolve as deeper commitments surface. These dissolutions are not betrayals. They are boundary conditions being discovered.

A Modest Reframe

If you find that no one quite ‘buys’ your full accounting, this need not be taken as failure or marginality. It may simply mean you are stopping at a different point of negation than most.

Heterodox work functions less like a manifesto and more like a sorting mechanism. It attracts those whose exclusion criteria overlap with yours and repels those who need different closures. That is not a defect. It is what apophatic alignment looks like in practice. If a heterodox space ever achieves total coherence, it has likely ceased to be heterodox and begun, quietly, to rebuild a doctrine.

For those of us who work by subtraction rather than synthesis, this can be oddly reassuring. The near-misses are not signs that something has gone wrong. They are signs that the negation has done its work. Shared refusals do not entail shared destinations.

They were never meant to. And that, too, is part of the heterodox condition.