The modern search for the truth of consciousness has the unmistakable smell of a desert expedition gone wrong.

Everyone agrees the elephant is real. Everyone insists it’s important. No one agrees what it is, where it’s going, or whether it’s moving in circles. Still, the caravan marches on, convinced that the next dune will finally reveal solid ground.

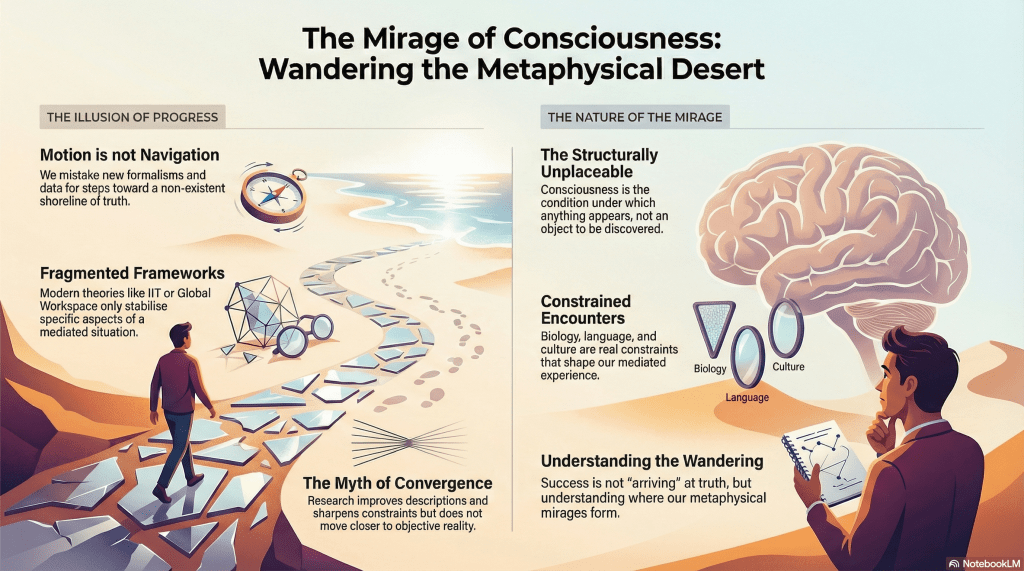

This confidence rests on a familiar Modern assumption: motion equals progress. We may not know where the shoreline of Truth lies, but surely we’re heading toward it. Each new theory, each new scan, each new formalism feels like a step forward. Bayesian updates hum reassuringly in the background. The numbers go up. Understanding must be improving.

But deserts are littered with travellers who swore the same thing.

The problem with consciousness is not that it is mysterious. It’s that it is structurally unplaceable. It is not an object in the world alongside neurons, fields, or functions. It is the mediated condition under which anything appears at all. Treating it as something to be discovered “out there” is like looking for the lens inside the image.

MEOW puts its finger exactly here. Consciousness is not a hidden substance waiting to be uncovered by better instruments. It is a constrained encounter, shaped by biology, cognition, language, culture, technology. Those constraints are real, binding, and non-negotiable. But they do not add up to an archetypal Truth of consciousness, any more than refining a map yields the territory itself.

Modern theories of consciousness oscillate because they are stabilising different aspects of the same mediated situation. IIT formalises integration. Global workspace models privilege broadcast. Predictive processing foregrounds inference. Illusionism denies the furniture altogether. Each feels solid while inhabited. Each generates the same phenomenology of arrival: now we finally see what consciousness really is.

Until the next dune.

Cognitively, we cannot live inside a framework we believe to be false. So every new settlement feels like home. Retrospectively, it becomes an error. Progress is narrated backwards. Direction is inferred after the fact. Motion is moralised.

Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.

— Søren Kierkegaard

The elephant keeps walking.

None of this means inquiry is futile. It means the myth of convergence is doing far more work than anyone admits. Consciousness research improves descriptions, sharpens constraints, expands applicability. What it does not do is move us measurably closer to an observer-independent Truth of consciousness, because no such bearing exists.

The elephant is not failing to reach the truth.

The desert is not arranged that way.

Once you stop mistaking wandering for navigation, the panic subsides. The task is no longer to arrive, but to understand where circles form, where mirages recur, and which paths collapse under their own metaphysical optimism.

Consciousness isn’t an elephant waiting to be found.

It’s the condition under which we keep mistaking dunes for destinations.