I mentioned in my last post about how Artificial Intelligence discovered a new variable—or, as the claim suggests, a new physics. This was a tie-in to the possible missing dimensions of human perception models.

Without delving too deep, the idea is that we can predict activity within dynamic systems. For example, we are all likely at least familiar with Newtonian physics—postulates such as F = ma [Force equals mass times acceleration or d = vt [distance equals velocity times time] and so on. In these cases, there are three variables that appear to capture everything we need to predict one thing given the other two that need to remain constant. Of course, we’d need to employ calculus instead of algebra if these are not constant. A dynamic system may require linear algebra instead.

When scientists represent the world, they tend to use maths. As such, they need to associate variables as proxies for physical properties and interactions in the world. Prominent statistician, George Box reminds us that all models are wrong, but some are useful. He repeated this sentiment many times, instructing us to ‘remember that models are wrong: the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful‘. But no matter how hard we try, a model will never be the real thing. The map cannot become the terrain, no matter how much we might expect it to be. By definition, a model is always an approximation.

All models are wrong but some are useful

George Box

In the Material Idealism post, the embedded video featuring Bernardo Kastrup equated human perception to the instrumentation panels of an aeroplane. Like the purported observer in a brain, the pilot can view the instruments and perform all matters of actions to manipulate the plane, including taking off, navigating through the environment, avoiding obstacles, and then landing. But this instrumentation provides only a representation of what’s ‘really’ outside.

Like mechanisms in the body, instrumentation can be ‘wired’ to trigger all sorts of warnings and alerts, whether breached thresholds or predictions. The brain serves the function of a predictive difference engine. It’s a veritable Bayesian inference calculator. Anil Seth provides an accessible summary in Being You. It relies on the senses to deliver input. Without these sense organs, the brain would be otherwise unaware and blinded from external goings on.

The brain cannot see or hear. It interprets inputs from eyes and ears to do so. Eyes capture light-oriented events, which are transmitted to the brain via optic nerves, and brain functions interpret this information into colour and shape, polarisation and hue, depth and distance, and so on. It also differentiates these data into friend or foe signals, relative beauty, approximate texture, and such. Ears provide a similar function within their scope of perception.

As mentioned, some animals have different sense perception capabilities and limitations, but none of these captures data not also accessible to humans via external mechanisms.

Some humans experience synesthesia, where they interpret certain stimuli differently, perhaps hearing colours or smelling music. We tend to presume that they are the odd ones out, but this assumption does not make it so. Perhaps these people are actually ahead of the rest of us on an evolutionary scale. I suppose time might sort that one out.

But here’s the point. Like the pilot, we can only experience what we are instrumented to experience, as limited to our sense perception and cognition faculties. If there are events not instrumented, it will be as if they don’t exist to the pilot. Can the pilot hear what’s happening outside?

This is the point of the AI experiment referenced above. Humans modelled some dynamic process that was presumed to be ‘good enough’, with the difference written off as an error factor. Artificial Intelligence, not limited to human cognitive biases, found another variable to significantly reduce the error factor.

According to the theory of evolution, humans are fitness machines. Adapt or perish. This is over-indexed on hereditary transmission and reproduction, but we are more vigilant for things that may make us thrive or perish versus aspects irrelevant to survival. Of course, some of these may be benign and ignored now but become maleficent in future. Others may not yet exist in our realm.

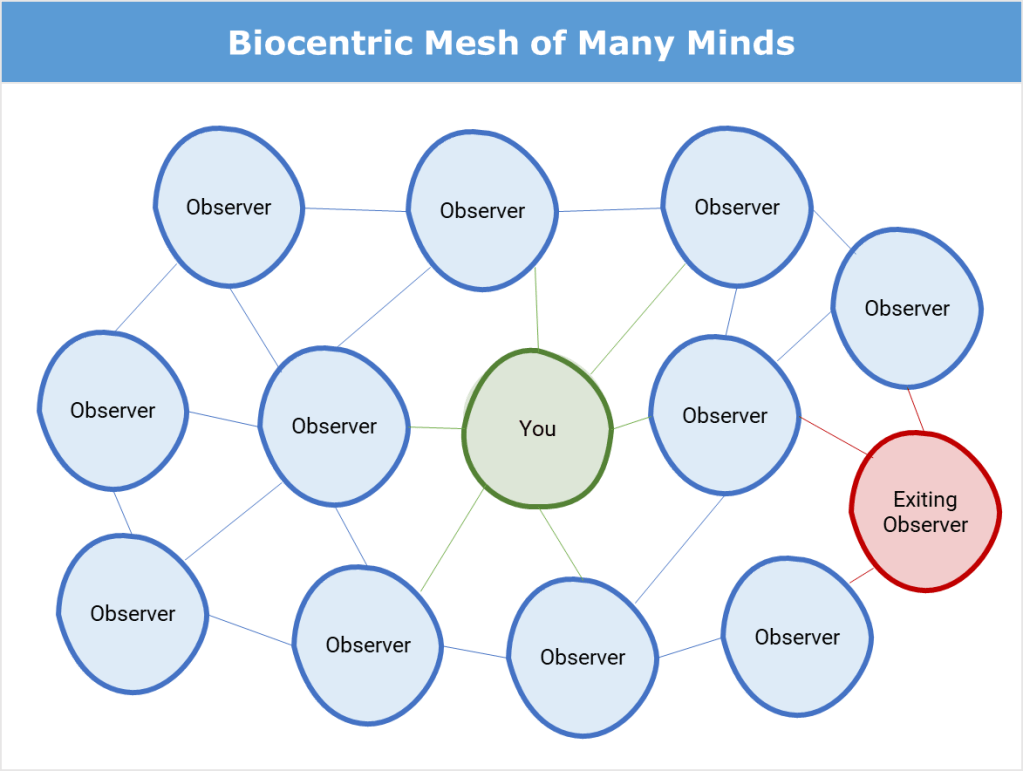

In either case, we can’t experience what we can’t perceive. And as Kastrup notes, some things not only evade perception but cannot even be conceived of.

I am not any more privileged than the next person to what these missing factors are nor the ramifications, but I tend to agree that there may be unknown unknowns forever unknowable. I just can’t conceive what and where.

I can’t wait to get back to my Agency focus.