The struggle is real. Last night, rather about 3 AM, I awakened with a thousand thoughts. This happens often enough. Some were creative ideas. Some were ideas for topics to write about here. Not just topics, but content as well. Then came the internal debate—whether to wake up and capture these ideas or to hope they’d remain in cache until the morning. All I can say it at least this one did. Well, the topic, at least.

The struggle is whether to lose sleep and risk not falling back to sleep to be able to awaken at a decent hour and not be dragging around the next day from lack of sleep. Or perhaps, at next notice, it would just be time to get up. All these scenarios have occurred at one time or another.

I tend to write a lot, whether for here, for work, for pleasure—whatever. I used to create visual art and certainly wrote a lot of songs or at least musical ideas that I hoped would develop into songs. The struggle was the same. The outcomes were as well.

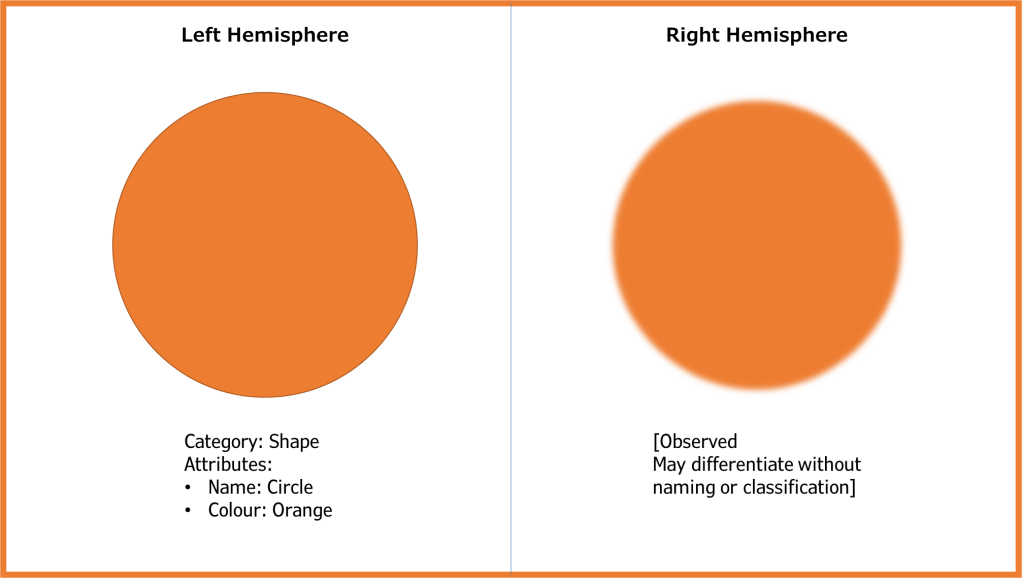

Having read as much as I have of McGilchrist, it starts to make sense. The right cerebral hemisphere is the font of creativity. It’s also the place for intuition and empathy. The left hemisphere is for symbols and categories. It’s the quarter for intellect. It’s also a bad roommate.

Whether or not one is creative does depend on the right hemisphere. Whether one can create depends on the left. Allow me to explain after laying out a relationship and three possibilities. For my purpose here, I can reduce the brain to three principal actors—the right hemisphere, the left hemisphere, and the frontal lobe.

As mentioned already, the right hemisphere generates creativity; the left hemisphere allows these ideas to be articulated symbolically, as in written and spoken words or art or music notation and so on; the frontal lobe acts as a mediator. Without getting too deep into neurology, a primary function of the frontal lobe is restrictive, which is to say it tells one or the other hemisphere to shut up and mind its business. Unfortunately, the hemispheres have this veto power of their own, so it’s difficult to fully understand the dynamics. This being said, let’s have a look at four scenarios that may illustrate why someone may or may not be able to create—in some cases even if they are otherwise creative.

I’ll start with the situation where the right hemisphere generates the creative ideas, and the other actors perform as expected. This is the brain of the creative person.

In the second scenario, the right hemisphere is simply weak. The person was just born with the bad luck of having a hemisphere that isn’t creative. In this case, there is nothing the left hemisphere or frontal lobe can do to compensate for this deficit. I’d like to think—like, perhaps being the wrong word—that this is where most non-creative people reside. They just don’t have that metaphorical creative gene.

In the third scenario, the right hemisphere generates plenty of creative thoughts, but the left hemisphere won’t “shut up”. If you’ve even had to think in a place with a lot of noise or distraction, you’ll get the gist. This is an imperfect analogy because creativity is precisely about not concentrating. Concentration is the enemy of creativity. So, in the case that the left hemisphere is interfering, it’s because it insists on concentrating, and that interrupts the creative process. In fact, it’s a misnomer to call something s creative process because creativity is precisely a lack of process. Like concentration, process kills creativity.

The right hemisphere is open and divergent.

The left hemisphere is closed and convergent.

In the fourth and last scenario, the right and left hemispheres are each playing their parts swimmingly, but the frontal lobe as moderator is deficient. In this case, the left is being itself and disrupting. Like the parable of the scorpion and the frog, it can’t help itself, but the frontal lobe isn’t telling it to be quiet and wait its turn. That’s the job of the frontal lobe. If you’ve ever witnessed a debate or mediated discussion where the moderator just lets the participants run rampant, you’ll know what I mean. Or perhaps you’ve been in a classroom or a meeting where the teacher or leader has no control of the class or the audience. It’s difficult to get anything accomplished.

Moving on. So, the actors each have their roles, but timing matters. The right hemisphere not only needs to generate thoughts or ideas, but it also needs time for them to incubate. Once they are ripe, only then is it ready to encounter the scrutiny of the left hemisphere and seek moderation for the frontal lobe.

If during the incubation process, the left hemisphere is continually asking, “Are we there yet? Are we there yet?” it’s unlikely one will ever get there.

If you are wondering how this works in the world of business and commerce—or better yet, you have already put together that this can’t possibly work in the realm of business and commerce—, I talk about that next. And I’ve got another segment on cerebral challenges in business in the works.

Creativity cannot be time-boxed. It can’t be summoned on demand. As already mentioned, it is not a process, and it can’t be tamed. Aside from the fickle public, have you ever wondered why so many musical artists are one-hit-wonders—if they have even been that lucky? These people had one idea—that happened to be an idea that would resonate in that moment—, but being told by the label to go generate some more hits is asking for creativity on demand.

Depending on your age and generation, some of you might be asking yourselves, “What about Taylor Swift or Ed Sheeran or the Beatles or Beethoven?” These people are clearly the exceptions. We could as well look at the Vincent van Gough of the world who didn’t experience acceptance until after his death. Clearly, his creativity was unrecognised by his contemporaries. Even in some of these exceptional cases, these people have found a voice and are applying a pattern. An example I like is that of Stephen King, who in an interview admitted that he has only had one good idea in his entire life, and he’s exploited it into a large number of books. So, he’s kept reskinning the same skeleton but with different dressings.

And as far as commerce goes, yes, these people are commercially successful. Some would argue about the actual talent. I’ve seen philosophy classes compare the ‘high art’ of Shakespeare with the ‘low art’ of Matt Groening’s The Simpsons. Certainly, The Simpsons are culturally creative and commercially successful, but how creative is it really? How does one actually measure degrees of creativity?

My point is that these exceptional people are generating output once a year or every few years. In business, so-called creatives may be asked to generate new ‘creative’ content daily, weekly, or perhaps monthly. Creativity doesn’t work like this. Even if you asked Mozart to generate a new piece each week, this mechanical process might yield paydirt, but most would just be a formulaic rehash. In fact, if you talk to any top artist, they’ll tell you that what you see or hear is less than one per cent of their ideas. Most are either partially formed or, upon reflection, just bad. They felt good at the time, but they couldn’t develop into something better, or they turned out to be derivative, which is hardly creative.

So business is a death sentence for creativity. The creative people I know, don’t get their creative jollies from their day jobs. They get it from their side projects, from their passion projects, and whether or not these projects are commercially viable.

In fact, I can also look at someone like Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain who was creative at the start—when they were under the radar—, but once they rose into view, he lost it, and then we lost him.

I hope this gives you a better feeling of how creativity works from the perspective of the brain and why we see so little creativity in the real world and even less in the business world. Do you find this surprising, or are you thinking, “man, this bloke must be dense if he’s just catching on to this now”?

Let me know in the comments.