…except, sometimes they are.

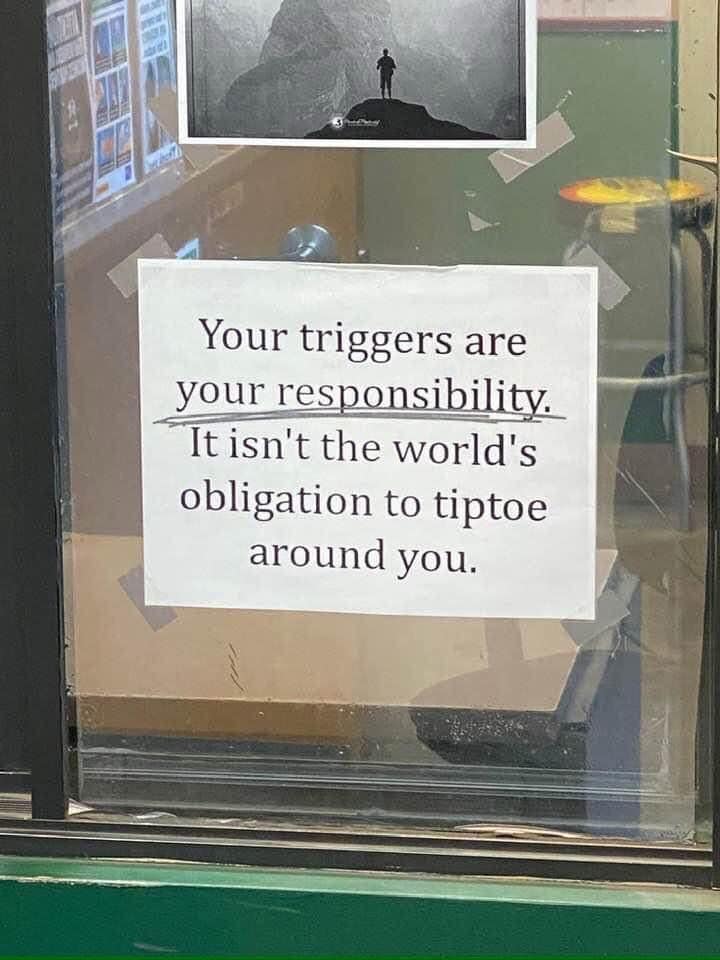

This came across my feed, the laminated wisdom of our times: Your triggers are your responsibility. It isn’t the world’s obligation to tiptoe around you. A phrase so crisp, so confident, it practically struts. You can imagine it on a mug, alongside slogans like Live, Laugh, Gaslight. These are the language games I love to hate.

Now, there’s a certain truth here. Life is hard, and people aren’t psychic. We can’t reasonably expect the world to read our mental weather reports—50% chance of anxiety, rising storms of existential dread. In an adult society, we are responsible for understanding our own emotional terrain, building the bridges and detours that allow us to navigate it. That’s called resilience, and it’s a good thing.

But (and it’s a big but) this maxim becomes far less admirable when you scratch at its glossy surface. What does triggers even mean here? Because trigger is a shape-shifter, what I term Shrödinger’s Weasels. For someone with PTSD, a trigger is not a metaphor; it’s a live wire. It’s a flashback to trauma, a visceral hijacking of the nervous system. That’s not just “feeling sensitive” or “taking offence”—it’s a different universe entirely.

Yet, the word has been kidnapped by the cultural peanut gallery, drained of precision and applied to everything from discomfort to mild irritation. Didn’t like that movie? Triggered. Uncomfortable hearing about your privilege? Triggered. This semantic dilution lets people dodge accountability. Now, when someone names harm—racism, misogyny, homophobia, you name it—the accused can throw up their hands and say, Well, that’s your problem, not mine.

And there’s the rub. The neat simplicity of Your triggers are your responsibility allows individuals to dress their cruelty as stoic rationality. It’s not their job, you see, to worry about your “feelings.” They’re just being honest. Real.

Except, honesty without compassion isn’t noble; it’s lazy. Cruelty without self-reflection isn’t courage; it’s cowardice. And rejecting someone’s very real pain because you’re too inconvenienced to care? Well, that’s not toughness—it’s emotional illiteracy.

Let’s be clear: the world shouldn’t have to tiptoe. But that doesn’t mean we’re free to stomp. If someone’s discomfort stems from bigotry, prejudice, or harm, then dismissing them as “too sensitive” is gaslighting, plain and simple. The right to swing your fist, as the old adage goes, ends at someone else’s nose. Likewise, the right to be “brutally honest” ends when your honesty is just brutality.

The truth is messy, as most truths are. Some triggers are absolutely our responsibility—old wounds, minor slights, bruised egos—and expecting the world to cushion us is neither reasonable nor fair. But if someone names harm that points to a broader problem? That’s not a trigger. That’s a mirror.

So yes, let’s all take responsibility for ourselves—our pain, our growth, our reactions. But let’s also remember that real strength is found in the space where resilience meets accountability. Life isn’t about tiptoeing or stomping; it’s about walking together, with enough care to watch where we step.