Abortion, Ontological Grammar, and the Limits of Civil Discourse

When federal abortion protections were withdrawn in the United States, many observers treated the event as a policy reversal, a judicial shift, or a partisan victory. Those are surface descriptions. They are not wrong. They are simply too thin.

What was exposed was not a failure of dialogue. It was the collision of ontological grammars.

1. Thick Concepts and the Illusion of Neutral Ground

Bernard Williams famously distinguished between ‘thin’ moral terms (good, bad, right) and ‘thick’ ones (cruel, courageous, treacherous), where description and evaluation are fused.

Abortion is not a thin concept. It is thick all the way down.

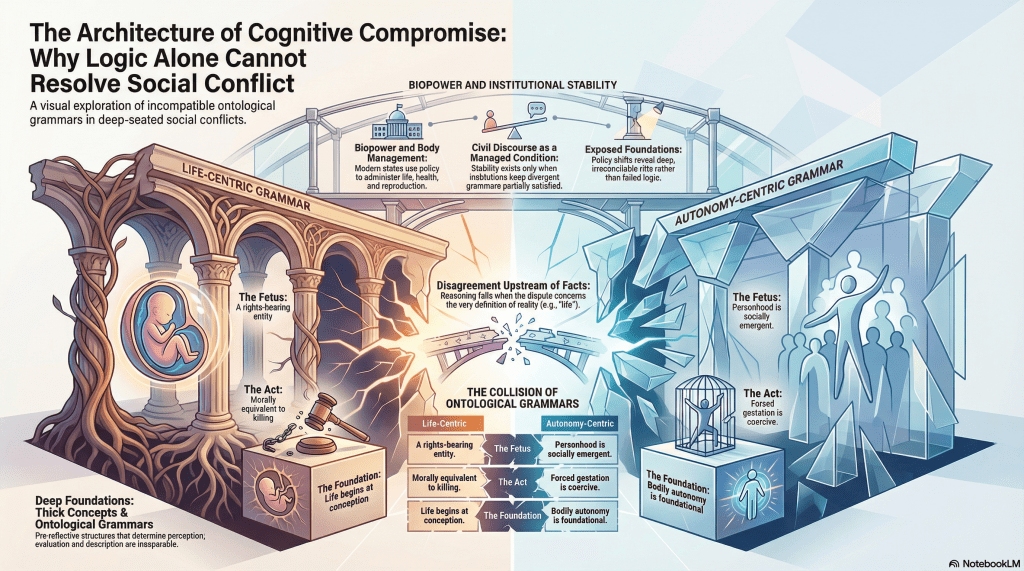

For one framework, the operative grammar is something like:

- Life begins at conception.

- The foetus is a rights-bearing entity.

- Termination is morally equivalent to killing.

For another:

- Personhood is socially and biologically emergent.

- Bodily autonomy is foundational.

- Forced gestation is coercive.

Notice that these are not competing policies. They are competing ontological commitments about what exists, what counts as a person, and what kind of being a pregnant body is.

Argument across this divide does not merely contest conclusions. It contests the background conditions under which reasons register as reasons.

This is not ‘people see the world differently’. It is: people parse reality through grammars that do not commute.

2. Ontological Grammar: Where Deliberation Stops

By ‘ontological grammar’, I do not mean syntax in the Saussurean or Chomskyan sense. I mean the pre-reflective substrate that structures what appears salient, real, morally charged, or negligible.

We deliberate within grammars. We do not deliberate our way into them.

Liberal Enlightenment optimism assumes that if disagreement persists, more information, better reasoning, or improved empathy will close the gap. But if the dispute concerns the very ontology of ‘life’, ‘person’, or ‘rights’, no amount of fact-sharing resolves the issue. The disagreement is upstream of facts.

The closure of federal abortion access did not prove that one side reasoned better. It demonstrated that institutional containment had failed.

3. Biopower and the Management of Bodies

Michel Foucault gives us a crucial lens: biopower. Modern states do not merely govern territory; they administer life. Birth rates, mortality, sexuality, health – these become objects of policy.

Abortion sits directly inside this matrix.

A state that restricts abortion is not only expressing moral judgment. It is reallocating control over reproductive capacity. It is asserting a claim over which bodies count, which futures are permitted, and which biological processes are subject to regulation.

The conflict is therefore not purely ethical. It is biopolitical.

And what appears as ‘civil discourse’ around abortion is often possible only so long as institutional frameworks keep both grammars partially satisfied. When federal protections existed, they acted as a stabilising superstructure. Remove that, and the ontological conflict becomes naked.

4. Habitus and the Illusion of Reasoned Consensus

Pierre Bourdieu would remind us that our dispositions are not self-authored. Habitus sedimented through family, religion, class, and institutional life shapes what feels obvious, outrageous, or unthinkable.

People do not wake up one morning and choose an abortion ontology.

They inherit it. It becomes embodied common sense.

Thus, when someone says, ‘Surely we can agree that making a person feel whole is more important than ideological purity’, they are already speaking from within a grammar that prioritises individual authenticity and psychological coherence. That priority is not universal. It is historically situated.

Compromise is not achieved by stepping outside habitus. It is achieved when institutional and social conditions allow divergent grammars to coexist without totalising one another.

5. The Popperian Threshold

It is impossible to speak in such a way that you cannot be misunderstood.

—Karl Popper

Karl Popper warned of the ‘paradox of tolerance‘: unlimited tolerance may enable intolerant forces to eliminate tolerance itself.

In particularly virulent climates, appeals to compromise are heard not as gestures of goodwill but as tactical weakness.

When one faction succeeds in unilaterally redefining the legal status of abortion at a federal level, it is not merely participating in discourse. It is altering the biopolitical infrastructure. Once altered, the range of permissible disagreement narrows.

Civil discourse, then, is not a natural equilibrium. It is a managed condition sustained by institutional design, social trust, and shared legibility.

NB: Popper’s paradox of tolerance is often invoked as a moral axiom. But it is better understood as a self-protective clause internal to liberal ontology. It presupposes a shared commitment to rational exchange. When that commitment erodes, the paradox does not resolve disagreement; it merely marks the point at which biopower intervenes to preserve a regime.

6. Why This Is Not Just ‘People Disagree’

The lay intuition – ‘people see the world differently’ – is descriptively correct and analytically useless.

What the ontological grammar model adds is structure:

- Disagreements cluster around thick concepts.

- Thick concepts fuse description and evaluation.

- Frameworks determine what counts as a reason.

- Institutions temporarily stabilise incompatible grammars.

- When stabilisation weakens, conflict appears irreconcilable.

Abortion is not uniquely polarising because people are irrational. It is polarising because it touches ontological primitives: life, personhood, autonomy, and obligation.

In such cases, ‘compromise’ is not achieved by discovering a middle truth. It is achieved – if at all – by constructing a legal and institutional arrangement that both grammars can grudgingly inhabit.

7. The Uncomfortable Conclusion

The Enlightenment story tells us that disagreement is a surface phenomenon, curable by better reasoning.

The ontological grammar story tells us something harsher: some disagreements are not resolvable through language because they are about the conditions under which language binds.

This does not entail quietism. It entails clarity.

Civil discourse is not proof that grammars have converged. It is evidence that power, institutions, and habitus have aligned sufficiently to prevent rupture.

When that alignment shifts, the illusion of shared ontology evaporates.

And what we are left with is not failed reasoning – but exposed foundations.

I planned to use prostitution and anti-natalism as other cases for elucidation, but I see this has already grown long. I’ll reserve these are others for another day and time.