I’ve long had a problem with Truth – or at least the notion of it. It gets way too much credit for doing not much at all. For a long time now, philosophers have agreed on something uncomfortable: Truth isn’t what we once thought it was.

Truth isn’t what we once thought it was

The grand metaphysical picture, where propositions are true because they correspond to mind-independent facts, has steadily eroded. Deflationary accounts have done their work well. Truth no longer looks like a deep property hovering behind language. It looks more like a linguistic device: a way of endorsing claims, generalising across assertions, and managing disagreement. So far, so familiar.

What’s less often asked is what happens after we take deflation seriously. Not halfway. Not politely. All the way.

That question motivates my new paper, Truth After Deflation: Why Truth Resists Stabilisation. The short version is this: once deflationary commitments are fully honoured, the concept of Truth becomes structurally unstable. Not because philosophers are confused, but because the job we keep asking Truth to do can no longer be done with the resources we allow it.

The core diagnosis: exhaustion

The paper introduces a deliberately unromantic idea: truth exhaustion. Exhaustion doesn’t mean that truth-talk disappears. We still say things are true. We still argue, correct one another, and care about getting things right. Exhaustion means something more specific:

After deflation, there is no metaphysical, explanatory, or adjudicative remainder left for Truth to perform.

Truth remains grammatically indispensable, but philosophically overworked.

The dilemma

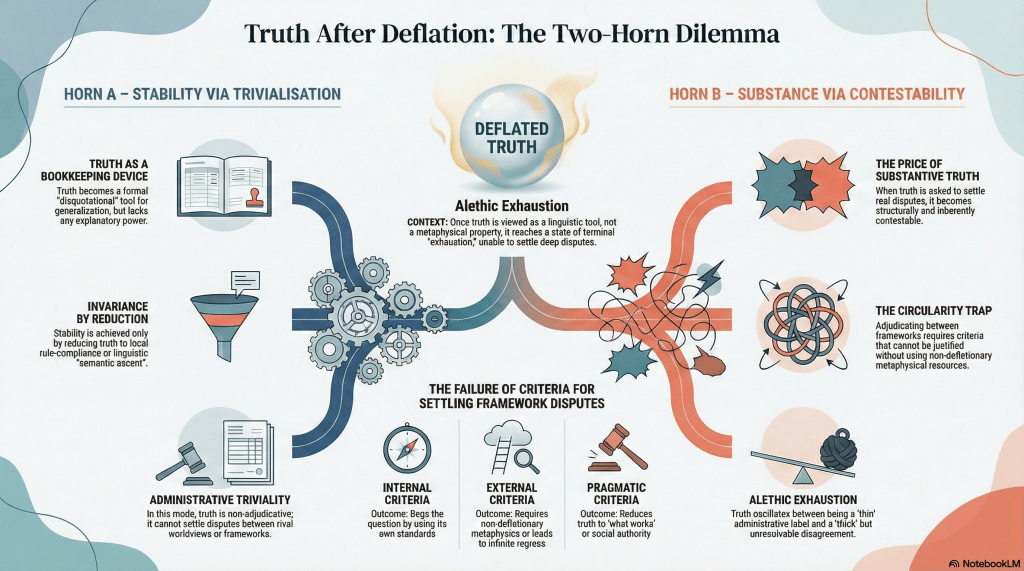

Once deflationary constraints are accepted, attempts to “save” Truth fall into a simple two-horn dilemma.

Horn A: Stabilise truth by making it invariant.

You can do this by disquotation, stipulation, procedural norms, or shared observation. The result is stable, but thin. Truth becomes administrative: a device for endorsement, coordination, and semantic ascent. It no longer adjudicates between rival frameworks.

Horn B: Preserve truth as substantive.

You can ask Truth to ground inquiry, settle disputes, explain success, or stand above practices. But now you need criteria. And once criteria enter, so do circularity, regress, or smuggled metaphysics. Truth becomes contestable precisely where it was meant to adjudicate.

Stability costs substance. Substance costs stability. There is no third option waiting in the wings.

Why this isn’t just abstract philosophy

To test whether this is merely a theoretical artefact, the paper works through three domains where truth is routinely asked to do serious work:

- Moral truth, where Truth is meant to override local norms and condemn entrenched practices.

- Scientific truth, where Truth is meant to explain success, convergence, and theory choice.

- Historical truth, where Truth is meant to stabilise narratives against revisionism and denial.

In each case, the same pattern appears. When truth is stabilised, it collapses into procedure, evidence, or institutional norms. When it is thickened to adjudicate across frameworks, it becomes structurally contestable. This isn’t relativism. It’s a mismatch between function and resources.

Why this isn’t quietism either

A predictable reaction is: isn’t this just quietism in better prose?

Not quite. Quietism tells us to stop asking. Exhaustion explains why the questions keep being asked and why they keep failing. It’s diagnostic, not therapeutic. The persistence of truth-theoretic debate isn’t evidence of hidden depth. It’s evidence of a concept being pushed beyond what it can bear after deflation.

The upshot

Truth still matters. But not in the way philosophy keeps demanding. Truth works because practices work. It doesn’t ground them. It doesn’t hover above them. It doesn’t adjudicate between them without borrowing authority from elsewhere. Once that’s accepted, a great deal of philosophical anxiety dissolves, and a great deal of philosophical labour can be redirected.

The question is no longer “What is Truth?” It’s “Why did we expect Truth to do that?”

The paper is now archived on Zenodo and will propagate to PhilPapers shortly. It’s long, unapologetically structural, and aimed squarely at readers who already think deflationary truth is right but haven’t followed it to its endpoint.

Read it if you enjoy watching concepts run out of road.