So sad, really. Not tragic in the noble Greek sense, just pathetically engineered. Our collective addiction to money isn’t even organic – it’s fabricated, extruded like a synthetically flavoured cheese product. At least fentanyl has the decency to offer a high. Money promises only more money, like a Ponzi scheme played out on the global stage, with no exit strategy but death – or worse, a lifestyle brand.

We’re told money is a tool. Sure. So’s a knife. But when you start sleeping with it under your pillow, stroking it for comfort, or stabbing strangers for your next fix, you’re not using it as a “tool” – you’re a junkie. And the worst part? It’s socially sanctioned. Applauded, even. We don’t shame the addict – we give him equity and a TED Talk.

The Chemical Romance of Currency

Unlike drugs, money doesn’t scramble your neurons – it rewires your worldview. You don’t feel high. You feel normal. Which is exactly what makes it so diabolical. Cocaine users might have delusions of grandeur, but capitalists have Excel sheets to prove theirs. It’s the only addiction where hoarding is a virtue and empathy is an obstacle to growth.

“We used to barter goods. Now we barter souls for subscriptions.”

The dopamine hit of a pay rise. The serotonin levels swell when your bank app shows four digits instead of three. These are chemical kicks masquerading as success. It’s not money itself – it’s the psychic sugar rush of “having” it, and the spiritual rot of needing it just to exist.

And oh, how they’ve gamified that need. You want to eat? Pay. You want shelter? Pay. You want healthcare? Pay – and while you’re at it, pay for the privilege of existing inside a system that turns your own exhaustion into a business model. You are the product. The addict. The asset. The mark.

The Fabrication of Need

Nobody needs money in the abstract. You need food. You need air. You need dignity, love, and maybe the occasional lie-in. Money only enters the picture because we’ve designed a world where nothing gets through the gates without it. Imagine locking the pantry, then charging your children rent for their own sandwiches. That’s civilisation.

“Money isn’t earned—it’s rationed. And you’re gaslit into thinking it’s your fault you’re hungry.”

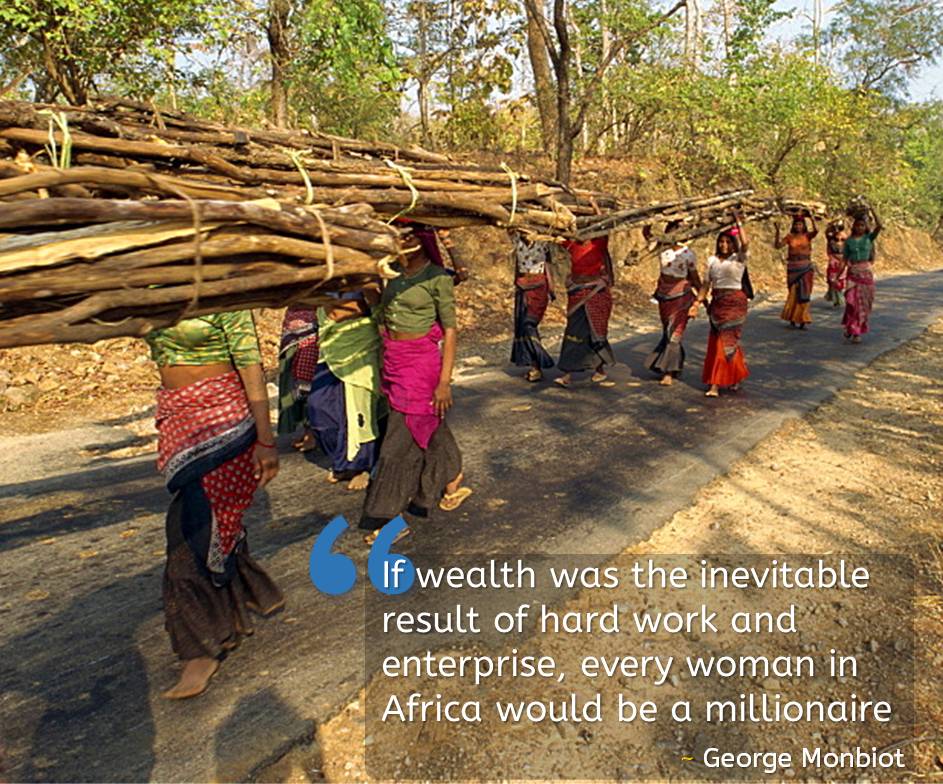

They say money is freedom. That’s cute. Tell that to the nurse working double shifts while Jeff Bezos experiments with zero-gravity feudalism. In reality, money is a filtering device—who gets to be human, and who stays stuck being labour.

Crypto was supposed to be liberation. Instead, it became a libertarian renaissance fair for the hyper-online, still pegged to the same logic: hoard, pump, dump, repeat. The medium changed, but the pathology remained the same.

Worshipping the Golden Needle

Let’s be honest: we’ve built temples to this thing. Literal towers. Financial cathedrals made of mirrored glass, each reflecting our collective narcotic fantasy of “more.” We measure our worth in net worth. We rank our lives by percentile. A person’s death is tragic unless they were poor, in which case it becomes a morality tale about poor decisions and not grinding hard enough.

“You’re not broke—you’re just not ‘optimising your earning potential.’ Now go fix your mindset and buy this online course.”

We no longer have citizens; we have consumers. No neighbours – just co-targeted demographics. Every life reduced to its purchasing power, its brand affiliations, its potential for monetisation. The gig economy is just Dickensian poverty with a better UI.

Cold Turkey for the Soul

The worst part? There is no rehab. No twelve-step programme for economic dependency. You can’t detox from money. Try living without it and see how enlightened your detachment feels on an empty stomach. You’ll find that society doesn’t reward transcendence – it punishes it. Try opting out and watch how quickly your saintliness turns into homelessness.

So we cope. We moralise the hustle. We aestheticise the grind. We perform productivity like good little addicts, jonesing for a dopamine hit in the shape of a direct deposit.

“At least fentanyl kills you quickly. Money lets you rot in comfort—if you’re lucky.”

Exit Through the Gift Shop?

So what’s the answer? I’m not offering one. This isn’t a TEDx talk. There’s no keynote, no downloadable worksheet, no LinkedIn carousel with three bullet points and an aspirational sunset. The first step is admitting the addiction – and maybe laughing bitterly at the absurdity of it all.

Money, that sweet illusion. The fiction we’ve all agreed to hallucinate together. The god we invented, then forgot was a puppet. And now we kneel, transfixed, as it bleeds us dry one tap at a time.

Epilogue: The Omission That Says It All

If you need proof that psychology is a pseudoscience operating as a control mechanism, ask yourself this:

Why isn’t this in the DSM?

This rabid, irrational, identity-consuming dependency on money – why is it not listed under pathological behaviour? Why isn’t chronic monetisation disorder a clinical diagnosis? Because it’s not a bug in the system. It is the system. You can be obsessed with wealth, hoard it like a dragon, destroy families and ecosystems in pursuit of it, and not only will you escape treatment, you’ll be featured on a podcast as a “thought leader.”

“Pathology is what the poor get diagnosed with. Wealth is its own immunity.”

We don’t pathologise the addiction to money because it’s the operating principle of the culture. And psychology – like any well-trained cleric of the secular age – knows not to bite the gilded hand that feeds it.

And so it remains omitted. Undiagnosed. Unquestioned. The dirtiest addiction of all, hidden in plain sight, wearing a suit and handing out business cards.