A Pollyanna Perspective

Chapter 5 of Yuval Noah Harari’s Nexus feels almost unlistenable, like polemic propaganda, painting cherry-picked anecdotes with a broad brush for maximal effect. If I hadn’t agreed to read this in advance, I’d have shelved the book long ago. It is as though Harari has never set foot on Earth and is instead relying on the optimistic narratives of textbooks and travel guides. His comparisons between democracy, dictatorship, and totalitarianism are so heavily spun and biased that they verge on risible. Harari comes across as an unabashed apologist for democracy, almost like he’s part of its affiliate programme. He praises Montesquieu’s separation of powers without noting how mistaken the idea as evidenced by modern-day United States of America. Not a fan. If you’re a politically Conservative™ American or a Torrey in the UK, you’ll feel right at home.

A Trivial Freedom – At What Cost?

Harari ardently defends the “trivial freedoms” offered by democracies whilst conveniently ignoring the shackles they impose. It’s unclear whether his Pollyanna, rose-coloured perspective reflects his genuine worldview or if he’s attempting to convince either himself or his audience of democracy’s inherent virtues. This uncritical glorification feels particularly out of touch with reality.

The Truth and Order Obsession

Once again, Harari returns to his recurring theme: the tradeoff between truth and order. His obsession with this dynamic overshadows more nuanced critiques. Listening to him defend the so-called democratic process that led to the illegal and immoral US invasion of Iraq in 2002 is nothing short of cringeworthy. Even more egregious is his failure to acknowledge the profound erosion of freedoms enacted by the PATRIOT Act, the compromised integrity of the offices of POTUS and SCOTUS, and the performative partisanship of Congress.

The Role of Media and Peer Review

Harari cites media and peer review as essential mechanisms for error correction, seemingly oblivious to the fallibility of these systems. His perception of their efficacy betrays a glaring lack of self-awareness. He overlooks the systemic biases, self-interest, and propaganda that permeate these supposed safeguards of democracy.

A Flimsy Narrative

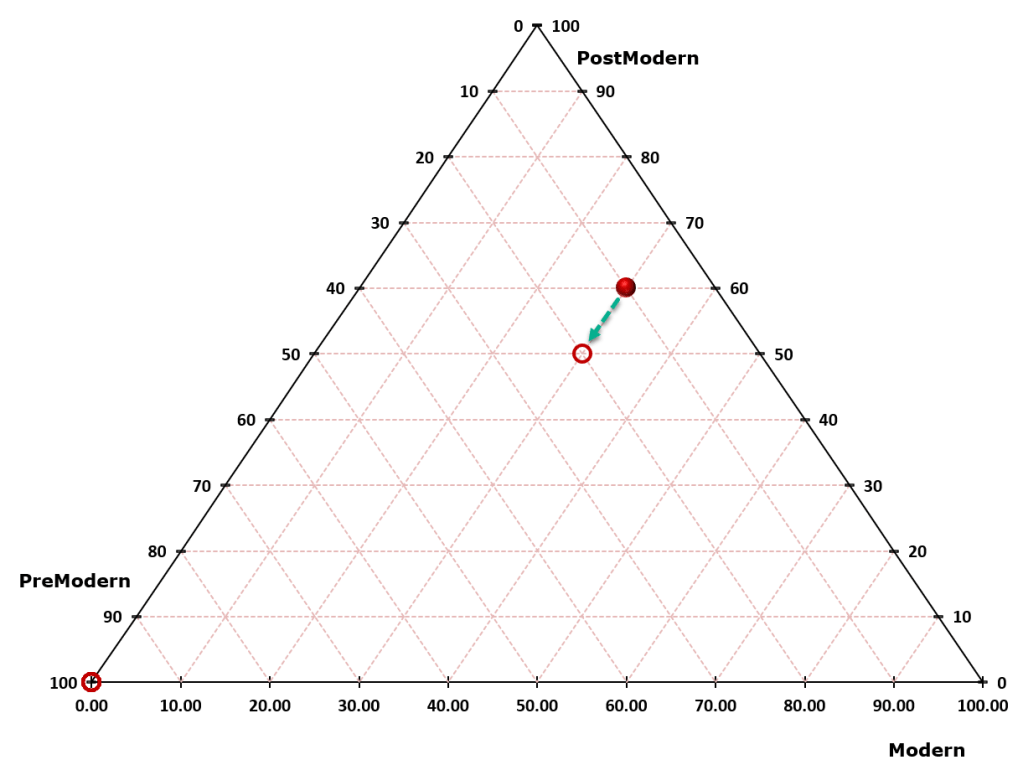

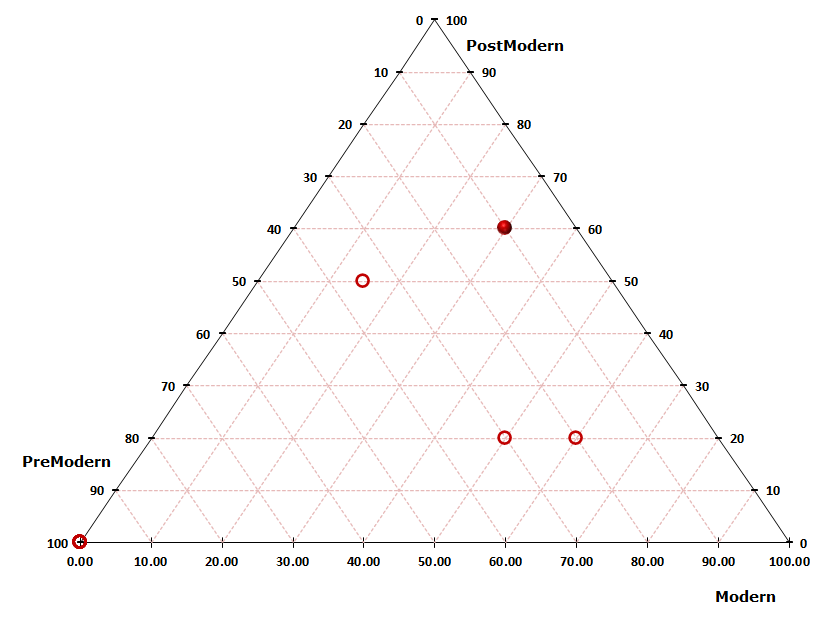

Whilst many Modernists might uncritically embrace Harari’s perspective, his argument’s veneer is barely a nanometre thick and riddled with holes. It’s not merely a question of critiquing metanarratives; the narrative itself is fundamentally flawed. By failing to engage with the complexities and contradictions inherent in democratic systems, Harari’s defence feels more like a sales pitch than a rigorous examination.

Final Thoughts

Harari’s Chapter 5 is a glaring example of uncritical optimism, where the faults of democracy are brushed aside in favour of a curated narrative of its virtues. This chapter does little to inspire confidence in his analysis and leaves much to be desired for those seeking a balanced perspective.