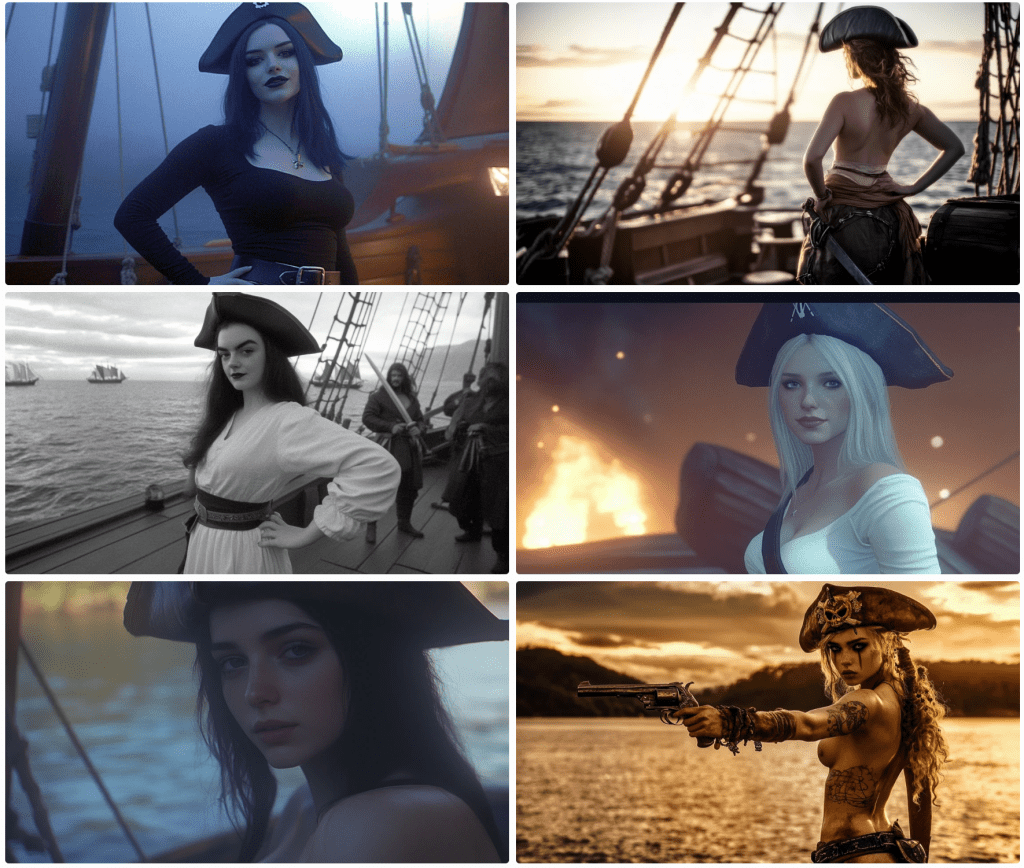

Thar be pirates. Midjourney 6.1 has better luck rendering pirates.

I find it very difficult to maintain composition. 5 of these images are mid shots whilst one is an obvious closeup. For those not in the know, Midjourney renders 4 images from each prompt. The images above were rendered from this prompt:

portrait, Realistic light and shadow, exquisite details,acrylic painting techniques, delicate faces, full body,In a magical movie, Girl pirate, wearing a pirate hat, short red hair, eye mask, waist belt sword, holding a long knife, standing in a fighting posture on the deck, with the sea of war behind her, Kodak Potra 400 with a Canon EOS R5Notice that the individual elements requested aren’t in all of the renders. She’s not always wearing a hat; she does have red hair, but not always short; she doesn’t always have a knife or a sword; she’s missing an eye mask/patch. Attention to detail is pretty low. Notice, too, that not all look like camera shots. I like to one on the bottom left, but this looks more like a painting as an instruction notes.

In this set, I asked for a speech bubble that reads Arrr… for a post I’d written (on the letter R). On 3 of the 4 images, it included ‘Arrrr’ but not a speech bubble to be found. I ended up creating it and the text caption in PhotoShop. Generative image AI is getting better, but it’s still not ready for prime time. Notice that some are rendering as cartoons.

Some nice variations above. Notice below when it loses track of the period. This is common.

Top left, she’s (perhaps non-binary) topless; to the right, our pirate is a bit of a jester. Again, these are all supposed to be wide-angle shots, so not great.

The images above use the same prompt asking for a full-body view. Three are literal closeups.

Same prompt. Note that sexuality, nudity, violence, and other terms are flagged and not rendered. Also, notice that some of the images include nudity. This is a result of the training data. If I were to ask for, say, the pose on the lower right, the request would be denied. More on this later.

In the block above, I am trying to get the model to face the camera. I am asking for the hat and boots to be in the frame to try to force a full-body shot. The results speak for themselves. One wears a hat; two wear boots. Notice the shift of some images to black & white. This was not a request.

In the block above, I prompted for the pirate to brush her hair. What you see is what I got. Then I asked for tarot cards.

I got some…sort of. I didn’t know strip-tarot was actually a game.

Next, I wanted to see some duelling with swords. These are pirates after all.

This may not turn into the next action blockbuster. Fighting is against the terms and conditions, so I worked around the restrictions the best I could, the results of which you may see above.

Some pirates used guns, right?

Right? I asked for pistols. Close enough.

Since Midjourney wasn’t so keen on wide shots, I opted for some closeups.

This set came out pretty good. It even rendered some pirates in the background a tad out of focus as one might expect. This next set isn’t too shabby either.

And pirates use spyglasses, right?

Sure they do. There’s even a pirate flag of sorts on the lower right.

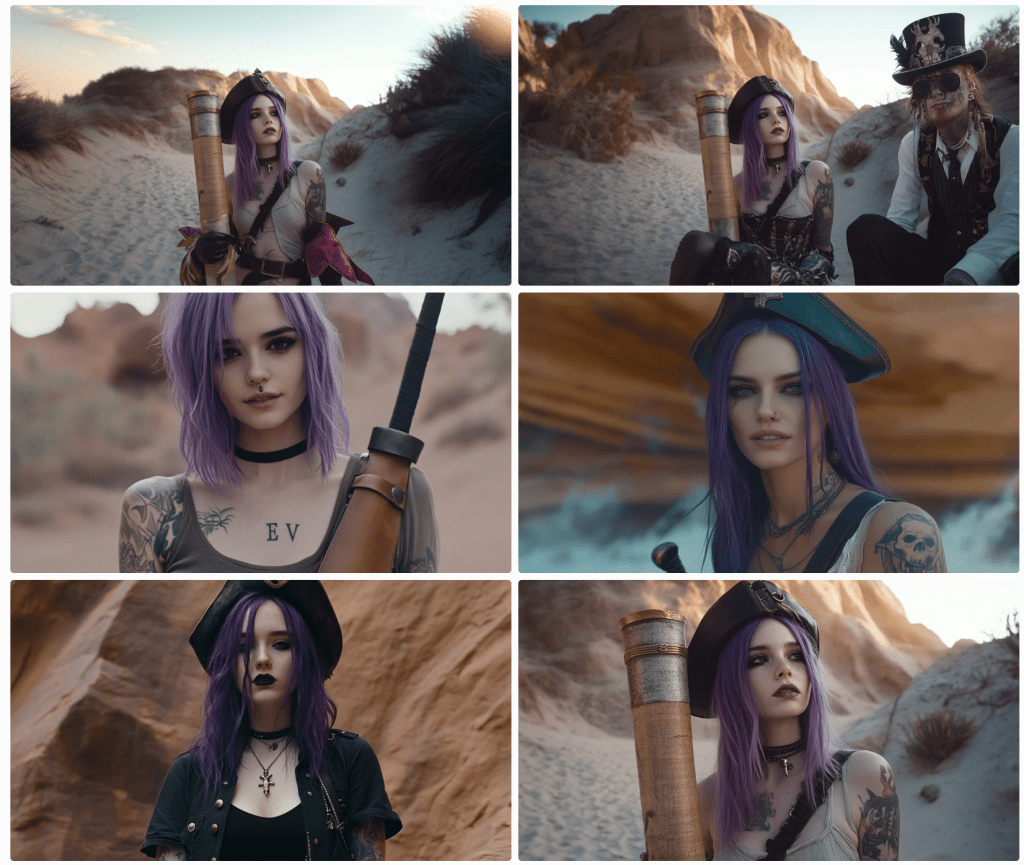

What happens when you ask for a dash of steampunk? I’m glad you asked.

Save for the bloke at the top right, I don’t suppose you’d have even noticed.

Almost to the end of the pirates. I’m not sure what happened here.

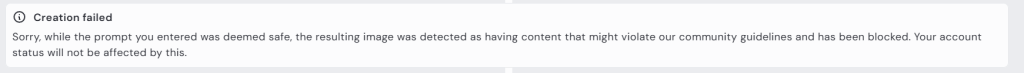

In the block above, Midjourney added a pirate partner and removed the ship. Notice again the nudity. If I ask for this, it will be denied. Moreover, regard this response.

To translate, this is saying that what I prompted was OK, but that the resulting image would violate community guidelines. Why can’t it take corrective actions before rendering? You tell me. Why it doesn’t block the above renders is beyond me – not that I care that they don’t.

This last one used the same prompt except I swapped out the camera and film instruction with the style of Banksy.

I don’t see his style at all, but I came across like Jaquie Sparrow. In the end, you never know quite what you’ll end up with. When you see awesome AI output, it may have taken dozens or hundreds of renders. This is what I wanted to share what might end up on the cutting room floor.

I thought I was going to go through pirates and cowboys, but this is getting long. if you like cowgirls, come back tomorrow. And, no, this is not where this channel is going, but the language of AI is an interest of mine. In a way, this illustrates the insufficiency of language.