These two words qualify as my words of the month: legibility and ontology.

I’ve been using them as lenses.

I picked up legibility from James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, which is really a book about how well-intentioned schemes fail once reality is forced to become administrable. Ontology is an older philosophical workhorse, usually paired with epistemology, but I’m using it here in a looser, more pragmatic sense.

When I write, I write through lenses. Everyone does. Writing requires a point of view, even when we pretend otherwise.

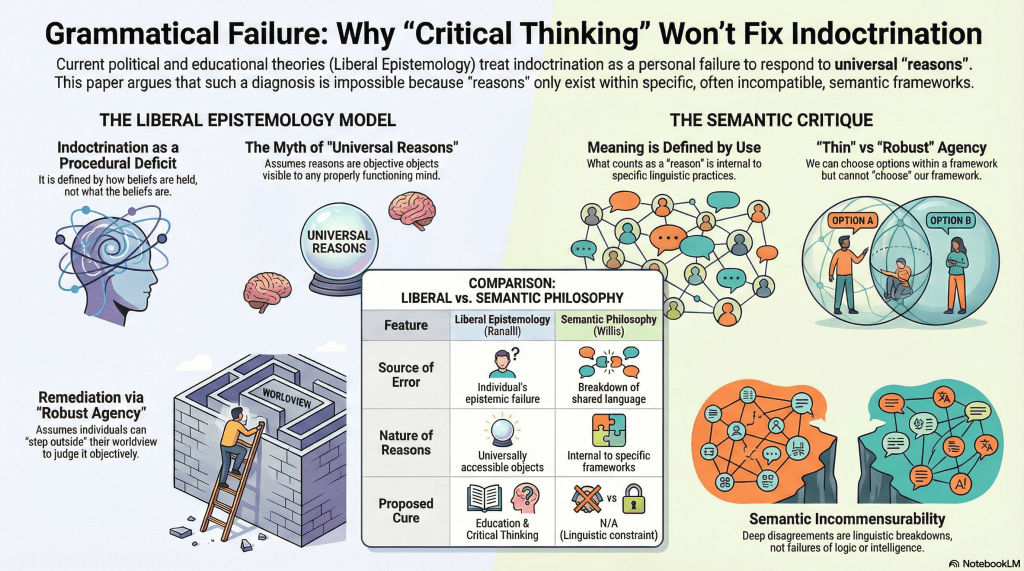

In this post, I want to talk more informally about my recent essay, Grammatical Failure. I usually summarise my work elsewhere, but here I want to think out loud about it, particularly in relation to social ontology and epistemology. I won’t linger on definitions. They’re a search away. But a little framing helps.

Ontology, roughly: how reality is parsed.

Epistemology: how knowledge is justified within that parsing.

Much of my recent work sits downstream of thinkers like Thomas Sowell, George Lakoff, Jonathan Haidt, Kurt Gray, and Joshua Greene. Despite their differences, they converge on a shared insight: human cognition is largely motivated preverbally. As a philosopher of language, that pre-language layer is where my interest sharpens.

I explored this in earlier work, including a diptych titled The Grammar of Impasse – Conceptual Exhaustion and Causal Mislocation. Writing is how I gel these ideas. There are several related pieces still in the pipeline.

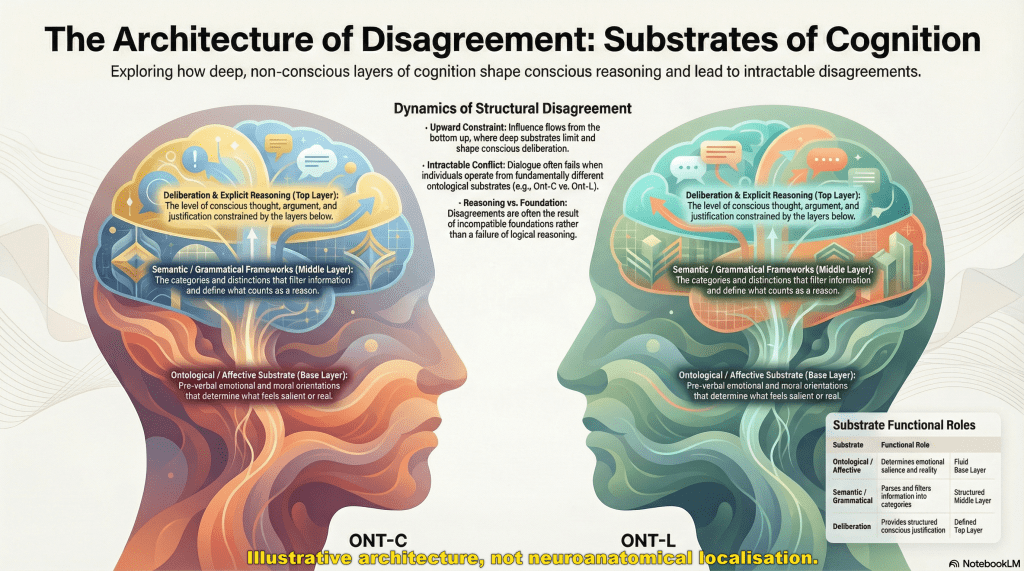

When I talk about grammar, I don’t mean Saussure or Chomsky. I mean something deeper: the ontological substrate beneath belief. Grammar, in this sense, is how reality gets parsed before beliefs ever form. It filters what can count as real, salient, or intelligible.

Let’s use a deliberately simplified example.

Imagine two ontological orientations. Call them Ont-C and Ont-L. This isn’t to say there are only two, but much of Western political discourse collapses into a binary anyway.

Ont-C tends to experience people as inherently bad, dangerous, or morally suspect. Ont-L tends to experience people as inherently good or at least corrigible. These aren’t opinions in the usual sense. They sit beneath belief, closer to affect and moral orientation.

Now consider retributive justice, setting aside the fact that justice itself is a thick concept.

From Ont-C, punishment teaches a lesson. It deters. It disciplines. From Ont-L, punishment without rehabilitation looks cruel or counterproductive, and the transgression itself may be read as downstream of systemic injustice.

Each position can acknowledge exceptions. Ont-L knows there are genuinely broken people. Ont-C knows there are saints. But those are edge cases, not defaults.

Now ask Ont-C and Ont-L to design a criminal justice system together. The result will feel intolerable to both. Too lenient. Too harsh. The disagreement isn’t over policy details. It’s over how reality is carved up in the first place.

And this is only one dimension.

Add others. Bring in Ont-V and Ont-M if you like, for vegan and meat-based ontologies. Suddenly, you have Ont-CV, Ont-CM, Ont-LV, and Ont-LM. Then add class, religion, gender, authority, harm, and whatever. Intersectionality stops looking like a solution and starts looking like a combinatorial explosion.

The Ont-Vs can share a meal, so long as they don’t talk politics.

The structure isn’t just unstable. It was never stable to begin with. We imagine foundations because legibility demands them.

Grammatical Failure is an attempt to explain why this instability isn’t a bug in liberal epistemology but a structural feature. The grammar does the sorting long before deliberation begins.

More on that soon.

In any case, once you start applying this ontological lens to other supposedly intractable disputes, you quickly realise that their intractability is not accidental.

Take abortion.

If we view the issue through the lenses of Ont-A (anti-abortion) and Ont-C (maternal choice), we might as well be peering through Ont-Oil and Ont-Water. The disagreement does not occur at the level of policy preferences or competing values. It occurs at the level of what counts as morally salient in the first place.

There is no middle ground here. No middle path. No synthesis waiting to be negotiated into existence.

That is not because the participants lack goodwill, intelligence, or empathy. It is because the ontological primitives are incommensurate. Each side experiences the other not as mistaken but as unintelligible.

We can will compromise all we like. The grammar does not comply.

Contemporary discourse often insists otherwise. It tells us that better arguments, clearer framing, or more dialogue will eventually converge. From this perspective, that insistence is not hopeful. It is confused. It mistakes a grammatical fracture for a deliberative failure.

You might try to consider other polemic topics and notice the same interplay.