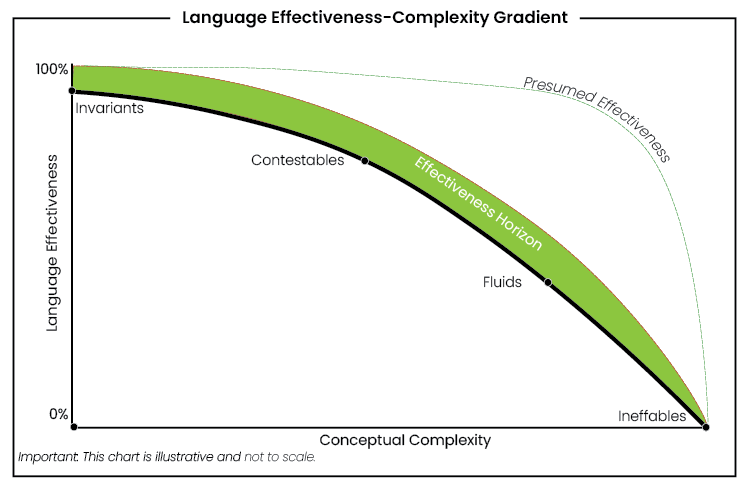

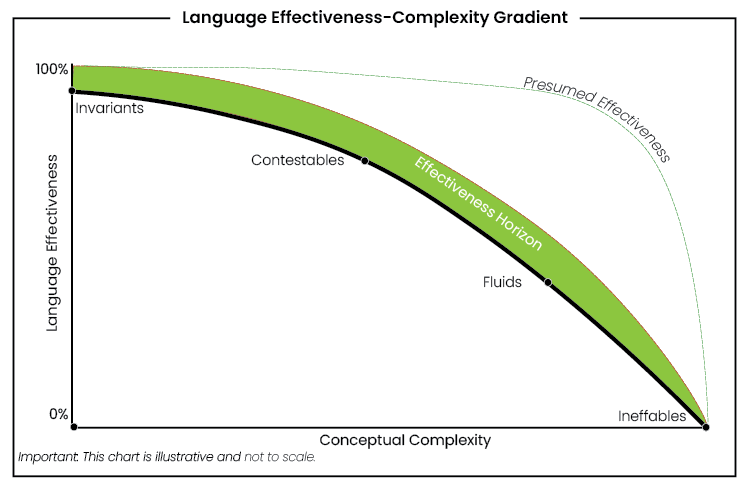

In a 4-minute video, I discuss The Gradient, Chapter 3 of my latest book, A Language Insufficiency Hypothesis.

It’s a short video/chapter. Nothing much to add. In retrospect, I should have summarised chapters 3 and 4 together.

Socio-political philosophical musings

In a 4-minute video, I discuss The Gradient, Chapter 3 of my latest book, A Language Insufficiency Hypothesis.

It’s a short video/chapter. Nothing much to add. In retrospect, I should have summarised chapters 3 and 4 together.

As I continue to react to Harari’s Nexus, I can’t help but feel like a curmudgeon. Our worldviews diverge so starkly that my critique begins to feel like a petty grudge—as though I am inconsolable. Be that as it may, I’ll persist. Please excuse any revelatory ad hominems that may ensue.

Harari is an unabashed Zionist and unapologetic nationalist. Unfortunately, his stories, centred on Israel and India, don’t resonate with me. This is fine—I’m sure many people outside the US are equally weary of hearing everything framed from an American perspective. Still, these narratives do little for me.

Patriotism and property are clearly important to Harari. As a Modernist, he subscribes to all the trappings of Modernist thought that I rail against. He appears aligned with the World Economic Forum, portraying it as a noble and beneficial bureaucracy, while viewing AI as an existential threat to its control. Harari’s worldview suggests there are objectively good and bad systems, and someone must oversee them. Naturally, he presents himself as possessing the discernment to judge which systems are beneficial or detrimental.

In this chapter, Harari recounts the cholera outbreak in London, crediting it with fostering a positive bureaucracy to ensure clean water sources. However, he conflates the tireless efforts of a single physician with the broader bureaucratic structure. He uses this example, alongside Modi’s Clean India initiative, to champion bureaucracy, even as he shares a personal anecdote highlighting its flaws. His rhetorical strategy seems aimed at cherry-picking positive aspects of bureaucracy, establishing a strawman to diminish its negatives, and then linking these with artificial intelligence. As an institutionalist, Harari even goes so far as to defend the “deep state.”

Earlier, Harari explained how communication evolved from Human → Human to Human → Stories. Now, he introduces Human → Document systems, connecting these to authority, the growing power of administrators, and the necessity of archives. He argues that our old stories have not adapted to address the complexities of the modern world. Here, he sets up religion as another bogeyman. As a fellow atheist, I don’t entirely disagree with him, but it’s clear he’s using religion as a metaphor to draw parallels with AI and intractable doctrines.

Harari juxtaposes “death by tiger” with “death by document,” suggesting the latter—the impersonal demise caused by bureaucracy—is harder to grapple with. This predates Luigi Mangione’s infamous response to UnitedHealthcare’s CEO Brian Thompson, highlighting the devastating impact of administrative systems. Harari also briefly references obligate siblicide and sibling rivalry, which seem to segue into evolution and concepts of purity versus impurity.

Echoing Jonathan Haidt, Harari explores the dynamics of curiosity and disgust while reinforcing an “us versus them” narrative. He touches on the enduring challenges of India’s caste system, presenting yet another layer of complexity. Harari’s inclination towards elitism shines through, though he occasionally acknowledges the helplessness people face when confronting bureaucracy. He seems particularly perturbed by revolts in which the public destroys documents and debts—revealing what feels like a document fetish and an obsession with traceability.

While he lauds AI’s ability to locate documents and weave stories by connecting disparate content, Harari concludes the chapter with a segue into the next: a discussion of errors and holy books. Once again, he appears poised to draw parallels that serve to undermine AI. Despite my critiques, I’m ready to dive into the next chapter.