Few philosophical aphorisms travel as lightly and cut as confidently as Ockham’s Razor. “Do not multiply entities beyond necessity.” The phrase has the air of austere wisdom. It sounds disciplined, economical, rational. It promises clarity by subtraction. One imagines conceptual clutter swept aside by a single elegant stroke.

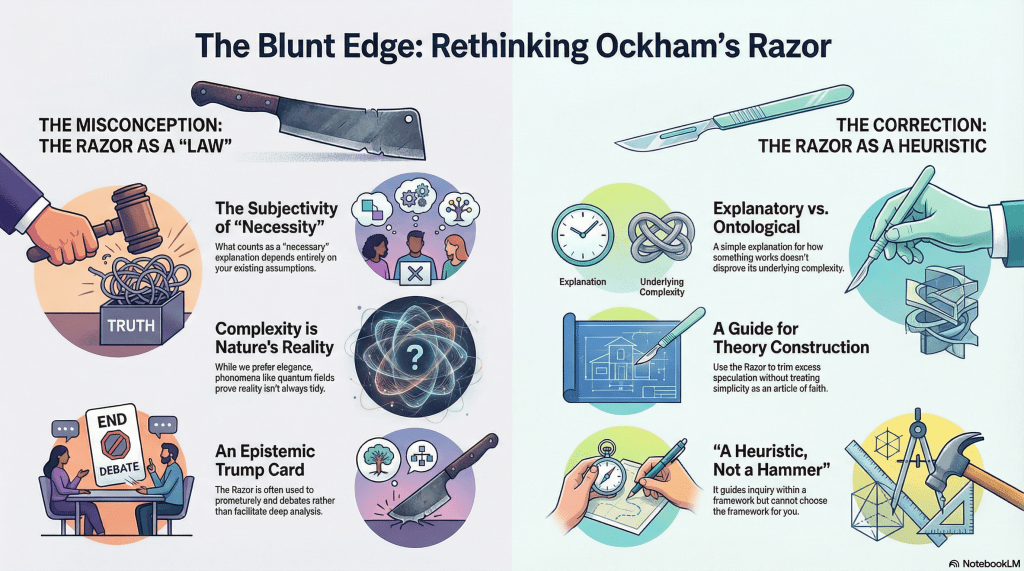

The Razor is attributed to William of Ockham, though like many slogans it has acquired a life far removed from its origin. In contemporary discourse it functions less as a methodological reminder and more as an epistemic trump card. The simpler explanation, we are told, is the better one. Case closed.

The trouble begins precisely there.

The Hidden Variable: Necessity

The Razor does not forbid multiplicity. It forbids unnecessary multiplicity. But who decides what is necessary?

Necessity is not a neutral category. It is already embedded within a framework of assumptions about what counts as explanation, what counts as sufficiency, and what counts as legitimate ontological commitment.

For one thinker, invoking a divine ground of physical law is unnecessary because the laws themselves suffice. For another, the laws are unintelligible without a grounding principle, and so God is necessary. Both can claim parsimony within their respective ontologies. The Razor does not adjudicate between them. It presupposes the grammar within which “necessity” is assessed.

The aphorism thus functions less as a rule and more as a reinforcement mechanism. It stabilises the commitments one already holds.

Parsimony Is a Heuristic, Not a Law

Science has often rewarded simplicity. Copernicus simplified celestial mechanics. Newton reduced motion to a few principles. Maxwell unified electricity and magnetism. These episodes encourage a romantic attachment to elegance.

Yet physics has also revealed a universe that is anything but tidy. Quantum fields, curved spacetime, dark matter, inflationary cosmology. Nature has shown little regard for our aesthetic preference for minimal furniture.

Parsimony, then, is pragmatic. It helps us avoid gratuitous complication. It disciplines theory formation. But it is not a metaphysical guarantee that reality itself is sparse.

To treat the Razor as if it carries ontological authority is to convert a methodological guideline into a philosophical dogma.

Structural Sufficiency Versus Metaphysical Surplus

The Razor becomes particularly contentious when deployed in debates about ultimate grounds. If a structural model explains observable regularities and survives empirical constraint, some conclude that any additional metaphysical layer is redundant.

This is a defensible position. It is also incomplete.

Redundancy in explanatory terms does not entail impossibility in ontological terms. A structural account of behaviour may render psychological speculation unnecessary for prediction, but it does not disprove the existence of inner motives. Likewise, a lawful cosmology may render a divine hypothesis explanatorily idle without rendering it incoherent.

The Razor trims explanatory excess. It does not settle metaphysical disputes.

Aphorisms as Closure Devices

Part of the Razor’s power lies in its compression. It is aphoristic. It travels easily. It signals intellectual seriousness. It sounds like disciplined thinking distilled.

But aphorisms compress complexity. They conceal premises. They discourage reopening the frame. “Follow the science.” “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” “Trust the market.” These phrases do not argue; they configure. They pre-load the space of acceptable interpretation.

Ockham’s Razor often operates in precisely this way. It is invoked not as the conclusion of a careful analysis but as a device to end discussion. The simpler view wins. Full stop.

Yet simplicity itself is indexed to perspective. What looks simple within one conceptual scheme may appear impoverished within another.

Tolerance for Explanatory Closure

There is also a psychological dimension worth acknowledging. Some individuals are comfortable with open explanatory ceilings. They accept that certain features of reality may lack ultimate grounding within their present framework. Others experience such openness as instability. They seek a final anchor.

The Razor favours the former temperament. It encourages ontological restraint and distrust of ultimate grounds. For those comfortable with structural sufficiency, this is liberating. For those who experience the absence of grounding as incomplete, it feels evasive.

The disagreement is not resolved by invoking parsimony. It reflects divergent tolerances for metaphysical closure.

When the Razor Becomes Inflationary

Ironically, the Razor can itself become an inflationary principle. It can elevate “simplicity” to a quasi-transcendental value. It can be treated as if reality owes us elegance.

At that point, the tool begins to govern the ontology rather than merely discipline it. The Razor becomes an article of faith, a universal heuristic immune to its own demand for justification.

One might then ask, with a certain symmetry: by what necessity is simplicity itself necessary?

A More Modest Use

None of this requires abandoning the Razor. It remains useful. It reminds us not to posit hidden mechanisms when observable structures suffice. It cautions against explanatory extravagance. It protects inquiry from baroque speculation.

But it should be treated as a heuristic, not a hammer. It guides theory construction within a framework. It does not choose the framework.

A more disciplined formulation would be this: when a structural account explains observed regularities under constraint and remains revisable, additional metaphysical posits do not increase explanatory power. Their adoption becomes a matter of ontological preference rather than necessity.

This preserves the Razor’s pragmatic value without inflating it into a metaphysical arbiter.

The Real Trouble

The real trouble with Ockham’s Razor is not that it cuts too much. It is that we often wield it without noticing the hand that holds it. We treat it as neutral when it is already embedded within a grammar of sufficiency, explanation, and legitimacy.

The Razor does not eliminate ontological commitment. It expresses one.

Recognising that does not blunt the blade. It merely reminds us that even the sharpest instruments are guided by the frameworks in which they are forged.

And frameworks, unlike aphorisms, are rarely simple.