A System Built on Exploitation and Neglect

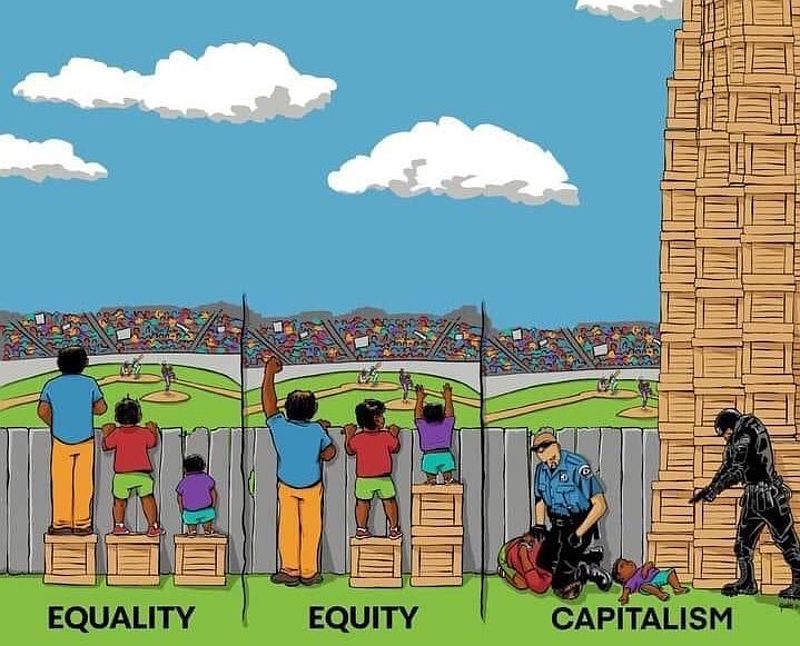

Capitalism, often celebrated for its ability to generate wealth and innovation, also brings with it a darker legacy: the untold millions of lives prematurely lost due to its systemic failures. Capitalism can be attributed to more than 10 million excess deaths per year, and these numbers will continue to increase. These deaths are not simply unfortunate byproducts but are structurally baked into the system itself. Whether through poverty, healthcare inequality, environmental destruction, or war, capitalism’s logic of profit maximisation places human life at the mercy of market forces, with devastating consequences.

Friedrich Engels famously referred to these preventable deaths as social murder, a term that highlights how capitalism creates conditions in which certain populations are systematically neglected, deprived, and ultimately destroyed. Today, Engels’ critique is more relevant than ever as we examine the staggering human toll that capitalism has left in its wake, often invisible in the glow of GDP figures and economic growth.

Poverty and Hunger: The Silent Killers

One of the most pervasive ways capitalism generates excess deaths is through poverty and hunger. Despite the extraordinary wealth produced by capitalist economies, millions still die from hunger-related causes every year. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 9 million people die annually from hunger and malnutrition, mostly in regions where capitalist-driven global inequality has made basic necessities unaffordable or inaccessible.[1]

Capitalism’s defenders often point to rising standards of living as evidence of the system’s success, but this narrative suffers from survivorship bias. The success stories of those who have benefited from capitalist growth obscure the countless lives that have been lost to the system’s structural inequalities. As Engels noted, these deaths are not natural or inevitable—they are preventable. They occur because the capitalist system concentrates wealth in the hands of a few while leaving vast populations to suffer without access to food, healthcare, or basic resources.

“For the dead, there is no measure of progress or rising standards; they are simply erased from the narrative.”

This disparity in wealth and access to resources creates a global system of social murder, where the deaths of the poor are written off as collateral damage in the pursuit of profit. These deaths are not merely unfortunate consequences; they are inherent to the capitalist system’s prioritisation of wealth accumulation over human life.

Healthcare Inequality and Preventable Deaths

The lack of access to adequate healthcare is another major driver of deaths attributable to capitalism. In the United States, the richest nation in the world, an estimated 500,000 deaths between 1990 and 2010 were linked to healthcare inequality, according to a Lancet study.[2] Globally, millions die each year from preventable causes—such as pneumonia, diarrhoea, and malaria—because market-driven healthcare systems fail to provide for those without the means to pay.

In a for-profit healthcare system, those without money are often denied life-saving treatment. Healthcare becomes a commodity, rather than a human right. This commodification of care creates deadly disparities, where a wealthy few receive world-class medical attention while millions die from treatable conditions. Engels’ notion of social murder is evident here as well: the system does not kill through direct violence but by neglecting the vulnerable.

“Capitalism’s market-driven healthcare system perpetuates a structural violence where the poor die from treatable conditions simply because they cannot pay.”

This situation is exacerbated by the ongoing commodification of healthcare through privatisation and austerity measures, which strip public systems of resources and force them to operate on capitalist principles. The result is a world where profit motives dictate who lives and who dies.

Environmental Destruction and Climate Change: Capitalism’s Long-Term Death Toll

Capitalism’s unrelenting focus on short-term profit also drives environmental destruction, contributing to a growing death toll linked to climate change. The WHO estimates that by 2030, climate change will cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths each year, driven by heat stress, malnutrition, and the spread of diseases like malaria and diarrhoea.[3] These figures are conservative, as the cascading effects of climate-induced migration and conflict are difficult to quantify.

David Harvey’s concept of accumulation by dispossession is central to understanding how capitalism contributes to environmental devastation. Capitalist economies extract and commodify natural resources, often at the expense of local populations who bear the brunt of environmental degradation. Deforestation, mining, and fossil fuel extraction displace communities and destroy ecosystems, creating conditions that lead to death, displacement, and disease.

“The victims of capitalism’s environmental destruction are not accidental casualties; they are the inevitable outcomes of a system that prioritises short-term profit over long-term sustainability.”

This environmental violence is compounded by disaster capitalism, a term coined by Naomi Klein to describe how capitalist interests exploit crises like natural disasters or financial collapses for profit.[4] The destruction of vulnerable communities by climate change is not simply a tragedy—it is a consequence of capitalist expansion into every corner of the planet, sacrificing human and ecological health for economic gain.

War and Imperialism: Capitalism’s Violent Expansion

The human toll of capitalism extends beyond poverty and environmental degradation to include the millions of lives lost to wars driven by capitalist interests. The illegal invasion of Iraq in 2003, for example, led to hundreds of thousands of deaths, many of which were tied to the geopolitical aims of securing control over oil reserves. Wars like Iraq are not isolated failures of policy but integral to the functioning of a global capitalist system that seeks to dominate resources and expand markets through military force.

David Harvey’s theory of new imperialism explains how capitalist economies rely on the expansion of markets and the extraction of resources from other nations, often through military means.[5] The military-industrial complex, as described by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, thrives under capitalism, profiting from perpetual war and the destruction of human life.

“Wars driven by capitalist interests are not just geopolitical strategies; they are extensions of capitalism’s relentless drive to dominate resources and secure markets.”

The death toll of wars driven by capitalist expansion is staggering. From the millions killed in conflicts over resources to the long-term destabilisation of regions like the Middle East, these deaths are directly tied to capitalism’s global ambitions. The victims of these wars—like those who suffer from poverty and environmental destruction—are casualties of a system that prioritises wealth and power over human life.

Conclusion: Reckoning with Capitalism’s Death Toll

The deaths attributable to capitalism are not abstract or incidental; they are the direct consequences of a system that places profit above all else. From hunger and poverty to healthcare inequality, environmental destruction, and war, the capitalist system has claimed millions of lives—lives that could have been saved under a more just and equitable economic model.

“Capitalism’s greatest violence is not its wars, but its everyday acts of neglect, where millions die not from bombs but from lack of food, water, and care.”

The true success of capitalism, then, is not in its ability to generate wealth for the few, but in its capacity to obscure the structural violence that sustains it. By framing poverty, healthcare inequality, and environmental destruction as unfortunate consequences of “market forces,” capitalism avoids accountability for the millions it leaves behind.

It is time to reckon with this hidden death toll. Only by facing the human cost of capitalism can we begin to imagine a future where economic systems prioritise human life over profit. The victims of capitalism are not just numbers—they are the casualties of a system that, as Engels pointed out, murders through neglect, exploitation, and greed.

Endnotes:

[1]: World Health Organization, “Hunger and Malnutrition: Key Facts,” 2022.

[2]: “The Lancet Public Health,” Study on healthcare inequality in the U.S., 2010.

[3]: World Health Organization, “Climate Change and Health,” 2022.

[4]: Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (Picador, 2007), pp. 9-10.

[5]: David Harvey, The New Imperialism (Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 145-147.