Girardian Lessons from a Violent Reckoning

The assassination of UnitedHealth CEO Brian Thompson is more than just a shocking headline—it’s a vivid tableau of modern society’s darkest impulses. For some, Thompson’s death represents long-overdue justice, a symbolic blow against the machinery of corporate greed. For others, it’s an unforgivable act of chaos that solves nothing. But as the dust settles, we’re left with an unsettling truth: both sides may be acting rationally, yet neither side emerges morally unscathed.

It’s not just about one man or one system—it’s about the cycles of conflict and violence that have defined human societies for millennia.

This event takes on deeper significance when viewed through the lens of René Girard’s theories on mimetic rivalry and the scapegoat mechanism. It’s not just about one man or one system—it’s about the cycles of conflict and violence that have defined human societies for millennia.

Mimetic Rivalry: The Root of Conflict

Girard’s theory begins with a simple observation: human desires are not unique; they are mimetic and shaped by observing what others want. This inevitably leads to rivalry, as individuals and groups compete for the same goals, power, or symbols of status. Left unchecked, these rivalries escalate into social discord, threatening to tear communities apart.

Enter the scapegoat. To restore order, societies channel their collective aggression onto a single victim, whose sacrifice momentarily alleviates the tension. The scapegoat is both a symbol of the problem and a vessel for its resolution—a tragic figure whose elimination unites the community in its shared violence.

Thompson as Scapegoat

In this story, Brian Thompson is the scapegoat. He was not the architect of the American healthcare system, but his role as CEO of UnitedHealth made him its most visible face. His decisions—denying claims, defending profits, and perpetuating a system that prioritises shareholders over patients—embodied the injustices people associate with healthcare in America.

manifesto of a society pushed to its breaking point

The assassin’s actions, however brutal, were a calculated strike against the symbol Thompson had become. The engraved shell casings found at the scene—inscribed with “Deny,” “Defend,” and “Depose”—were not merely the marks of a vigilante; they were the manifesto of a society pushed to its breaking point.

But Girard would caution against celebrating this as justice. Scapegoating provides only temporary relief. It feels like resolution, but it doesn’t dismantle the systems that created the conflict in the first place.

The Clash of Rationalities

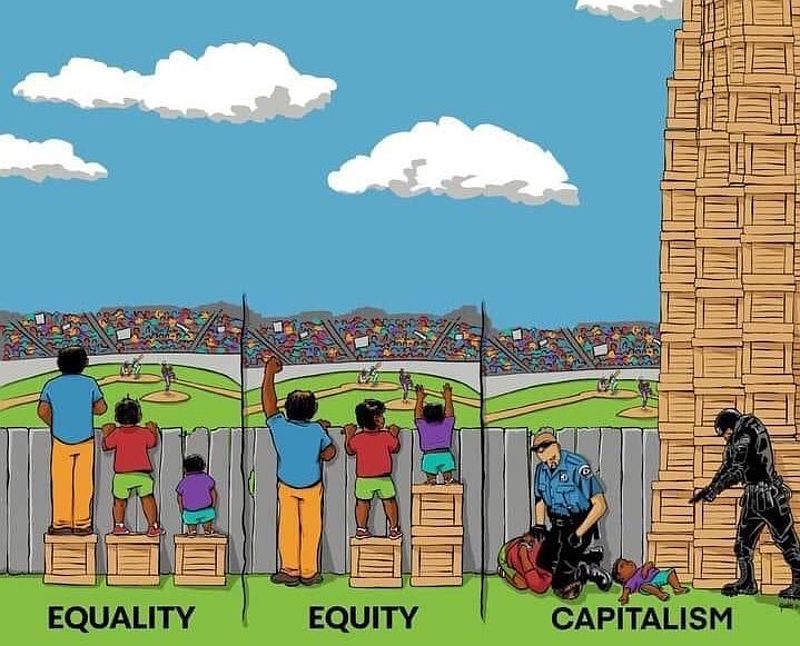

Both Thompson and his assassin acted rationally within their respective frameworks. Thompson’s actions as CEO were coldly logical within the profit-driven model of American capitalism. Deny care, maximise profits, and satisfy shareholders—it’s a grim calculus, but one entirely consistent with the rules of the system.

sacrifice one life to save countless others

The assassin’s logic is equally clear, though rooted in desperation. If the system won’t provide justice, then justice must be taken by force. From a Consequentialist perspective, the act carries the grim appeal of the trolley problem: sacrifice one life to save countless others. In this view, Thompson’s death might serve as a deterrent, forcing other executives to reconsider the human cost of their policies.

Yet Girard’s framework warns us that such acts rarely break the cycle. Violence begets violence, and the system adapts. The hydra of modern healthcare—the very beast Thompson represented—will grow another head. Worse, it may become even more entrenched, using this event to justify tighter security and greater insulation from public accountability.

“An Eye for an Eye”

Mahatma Gandhi’s warning, “An eye for an eye will only make the whole world blind,” resonates here. While the assassin may have acted with moral intent, the act itself risks perpetuating the very cycles of harm it sought to disrupt. The scapegoat mechanism may provide catharsis, but it cannot heal the underlying fractures in society.

Moving Beyond the Scapegoat

To truly break the cycle, we must confront the forces that drive mimetic rivalry and scapegoating. The healthcare system is just one manifestation of a larger problem: a society that prizes competition over cooperation, profit over people, and violence over dialogue.

The hydra story looms in the background here, its symbolism stark. Slaying one head of the beast—be it a CEO or a policy—will not bring about systemic change. But perhaps this act, as tragic and flawed as it was, will force us to reckon with the deeper question: How do we create a society where such acts of desperation are no longer necessary?

The answer lies not in finding new scapegoats but in dismantling the systems that create them. Until then, we remain trapped in Girard’s cycle, blind to the ways we perpetuate our own suffering.